1 University Institute for Research on Agricultural Resources (INURA), University of Extremadura, Avda. de la Investigación s/n, Campus Universitario, 06006 Badajoz, Spain

2 Institute of Food Science, Technology and Nutrition, Spanish National Research Council (ICTAN-CSIC), C/ José Antonio Novais, 10, 28040 Madrid, Spain

3. Cherry Times technical-scientific committee

The commercial quality of sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) depends critically on skin integrity; accordingly, susceptibility to water-induced cracking remains one of the major economic constraints for production (Gutiérrez et al., 2021; Brüggenwirth & Knoche, 2016).

Within this spectrum of epidermal disorders, aqueous spot has recently been described as an emerging pre- and postharvest condition in sweet cherry: symptoms may initiate on the tree, yet their expression typically intensifies during cold storage, compromising marketability, particularly in early cultivars such as ‘Burlat’ (Serradilla et al., 2021).

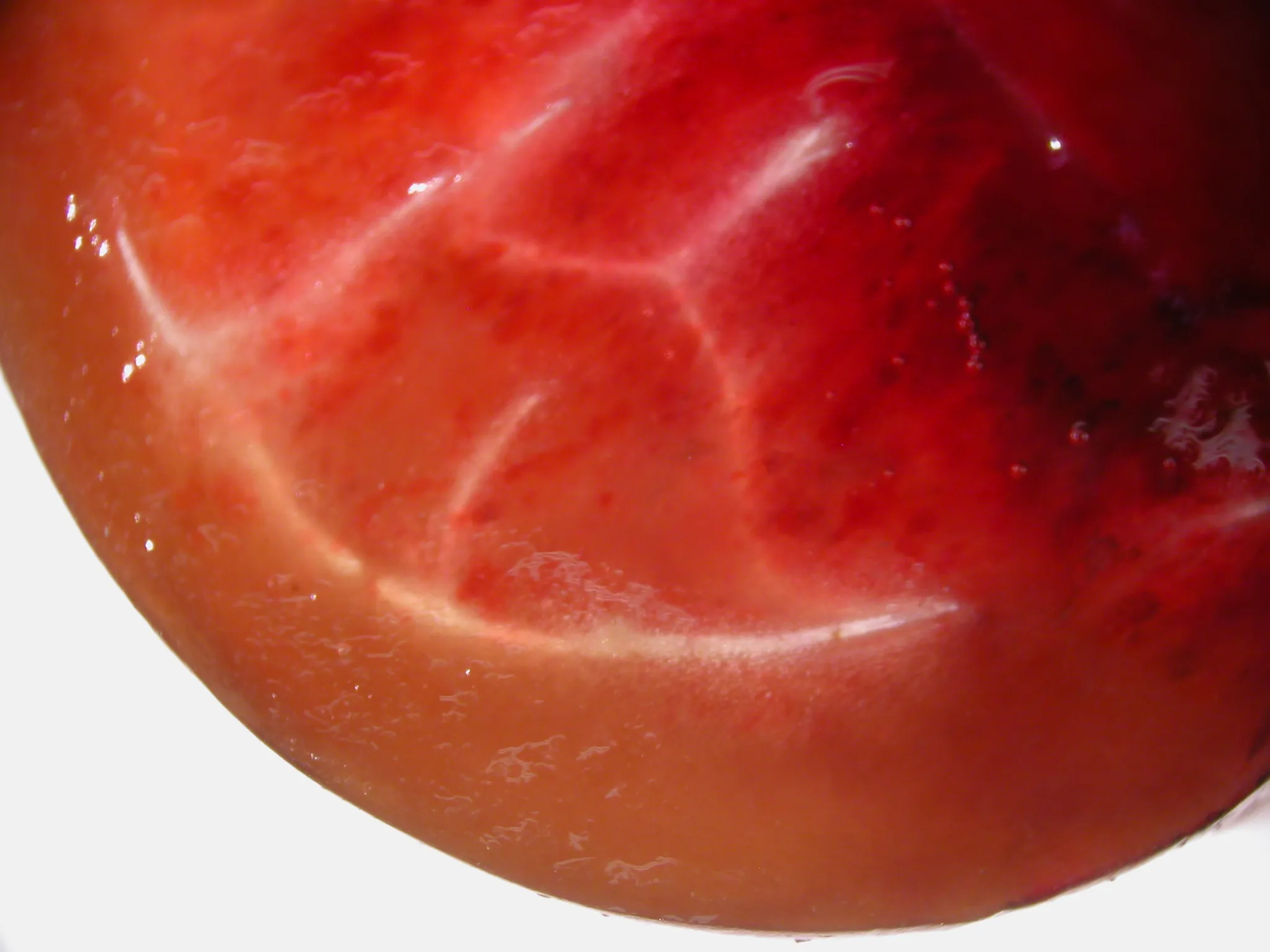

The characteristic external phenotype comprises depressed areas with a translucent, water-soaked appearance and, frequently, metallic-like discolorations, typically concentrated over the fruit “shoulders” and around the pedicel insertion (Fig. 1).

In Spain, the Special Conditions of the Cherry Orchard Insurance Scheme (Line 317, 2025 Plan) frame this type of epidermal damage within rain-risk coverage and define it as “metallic-like discolorations and/or reabsorptions that cause degradation of the fruit epidermis as a consequence of persistent water on the fruit during ripening, leading to loss of commercial value” (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Representative external symptoms of aqueous spot in sweet cherry ‘Burlat’.

Figure 1. Representative external symptoms of aqueous spot in sweet cherry ‘Burlat’.

From a physiopathological standpoint, the published evidence supports a scenario in which a structural and physiological predisposition of the exocarp may facilitate subsequent progression associated with microbial colonisation.

In an initial stage, the process is linked to mechanical failure of the fruit’s protective barrier, exacerbated by agroclimatic sequences characterised by rainfall followed by temperature increases, which promote prolonged retention of liquid water on the fruit surface (Serradilla et al., 2021).

During stage III of fruit growth, the exocarp is subjected to high elastic strain: the fruit continues to expand rapidly while deposition of new cuticular membrane (CM) is limited, such that the cuticle operates close to its mechanical threshold (Knoche et al., 2004; Peschel & Knoche, 2012).

This vulnerability has been described in detail for ‘Burlat’, whose mechanical and structural traits place it at the lower end of the resistance range reported for sweet cherry skin.

Specifically, ‘Burlat’ exhibits low values of the modulus of elasticity (E) and fracture pressure (P_fracture), indicative of limited resistance to skin extension (Brüggenwirth & Knoche, 2016).

It also shows among the lowest CM mass per unit area (≈0.95 g·m⁻²) and epicuticular wax loads (≈0.21 g·m⁻²) across evaluated cultivars (Peschel & Knoche, 2012).

Accordingly, ‘Burlat’ fruit requires, on average, only about one third of the water uptake needed for a more tolerant cultivar to reach skin fracture (WU₅₀ ≈ 50.5 mg; Brüggenwirth & Knoche, 2016).

This reduced robustness has also been associated with a lower cell-wall dry mass per unit fresh weight relative to less susceptible cultivars (Brüggenwirth & Knoche, 2016).

The combination of a relatively light cuticle, low stiffness and comparatively weaker cell walls means that exposure to liquid water or to high-humidity atmospheres markedly reduces CM fracture resistance (Knoche & Peschel, 2006; Winkler et al., 2020a).

Under such conditions, cuticular microcracks can develop, which are considered the earliest detectable sign of exocarp failure (Peschel & Knoche, 2005; Knoche & Peschel, 2006).

These defects impair the barrier function of the skin (Knoche & Peschel, 2006) and establish high-conductance pathways for water flux into underlying tissues (Weichert & Knoche, 2006).

Integrating these findings, a mechanistic framework can be proposed whereby localised water influx elevates turgor beyond the mechanical capacity of the outer parenchyma (Quero-García et al., 2021), leading to collapse of cell groups at the fruit periphery (Grimm et al., 2019; Winkler et al., 2020b).

This collapse is accompanied by the release of osmotically active solutes into the apoplast—including sugars, sorbitol and anthocyanins—(Winkler et al., 2020b), generating a matrix with loss of structural integrity and increased substrate availability.

As a consequence of the loss of structural integrity in the exocarp and outer parenchyma—and within a tissue environment of increased substrate availability—the clinical expression of aqueous spot manifests externally as depressed, translucent, water-soaked areas, often accompanied by progressive softening (Fig. 1).

On this background, a microbial consortium scenario has been reported, in which Botrytis cinerea has been detected at early stages within the mesocarp and, as deterioration progresses, co-occurrence of bacteria belonging to the order Enterobacterales has been observed.

This microbial component has been linked to progression towards extensive cellular breakdown and enzymatic maceration of the tissue and, at advanced stages, to the appearance of visible surface mycelium (Serradilla et al., 2021).

The aim of this study is to provide physiopathological insights into aqueous spot in sweet cherry ‘Burlat’ through an integrated characterisation of affected fruit.

To this end, fruit without visible lesions and fruit with aqueous spot were compared at an equivalent commercial maturity stage, combining complementary evidence on tissue expression of damage (structure and microstructure), compositional changes (phenolic profile), impacts on physicochemical quality (colour, firmness, soluble solids, titratable acidity and size), and the associated physiological response (respiration and ethylene production).

On this basis, we further assessed its expression in the optical signal across the visible and NIR ranges, as an initial step towards non-destructive diagnosis and as a prelude to subsequent hyperspectral analysis.

A central issue in interpreting aqueous spot in ‘Burlat’ is to determine whether the disorder is confined to the epidermis or involves subepidermal tissue collapse.

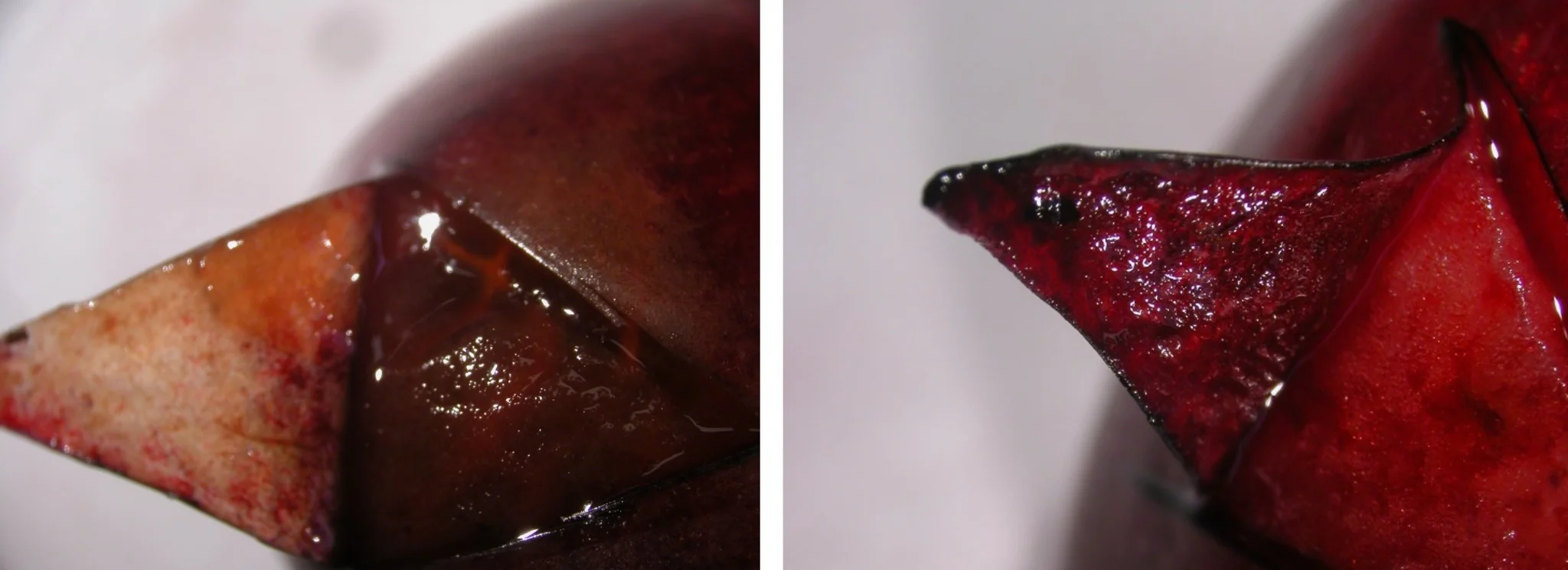

Fruit sectioning and comparative histology unambiguously localise the damage to the outer mesocarp and allow its effective depth to be delineated (Fig. 2; Fig. 3).

At the macroscopic level, partial sectioning of affected fruit reveals that, beneath the externally water-soaked area, a continuous band of subepidermal browning is present and is clearly demarcated from the inner tissue (Fig. 2).

This darkened zone is located within the outer mesocarp and defines a localised yet structurally relevant lesion, rather than a purely superficial colour change.

Figure 2. Partial section through the “shoulder” region of a ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry fruit with aqueous spot, viewed under a stereomicroscope, showing a subepidermal browning band in the outer mesocarp.

Figure 2. Partial section through the “shoulder” region of a ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry fruit with aqueous spot, viewed under a stereomicroscope, showing a subepidermal browning band in the outer mesocarp.

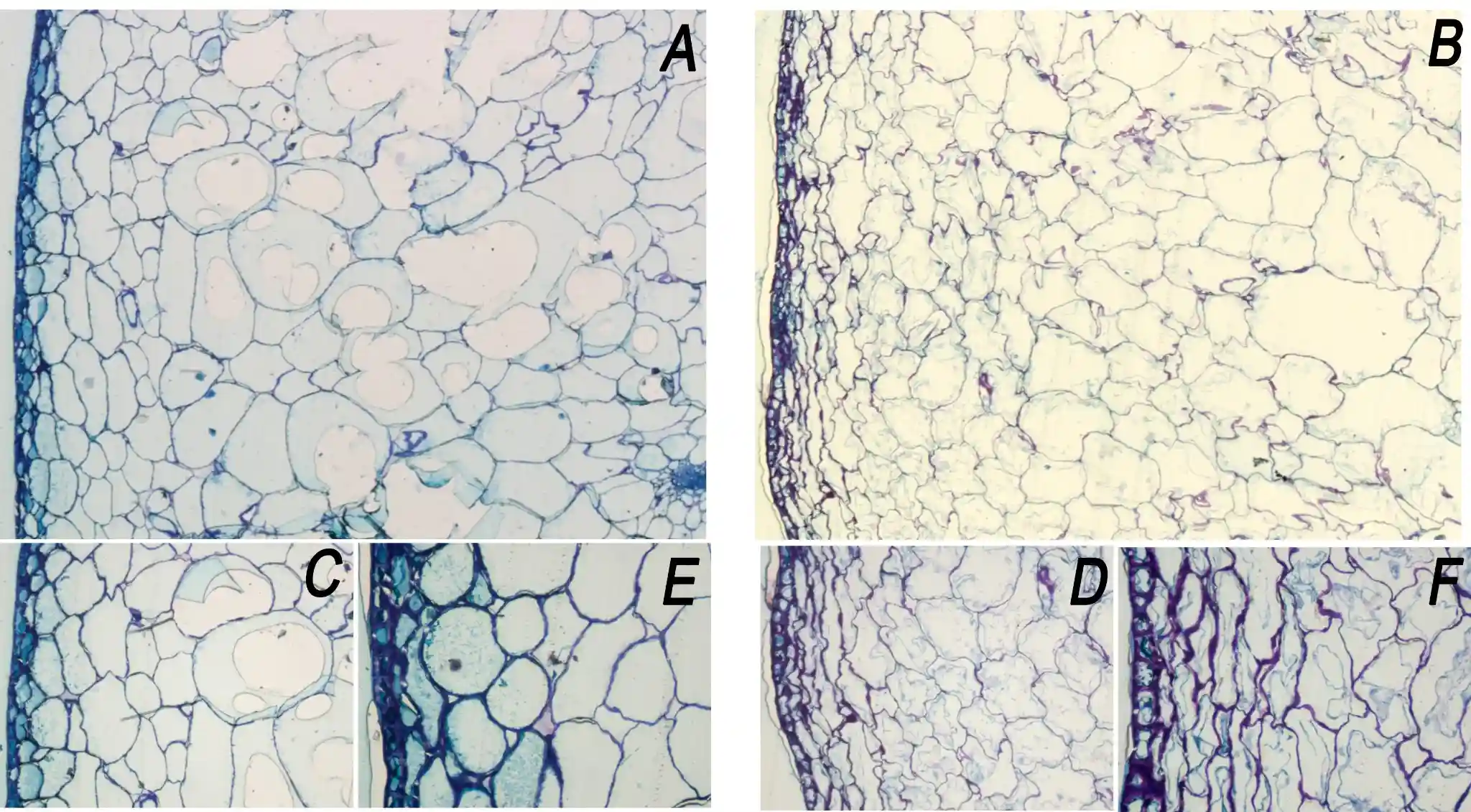

Comparative histology corroborates this pattern (Fig. 3). In healthy fruit, the epidermis forms a regular layer covered by a continuous cuticle, and the subepidermal parenchyma comprises predominantly isodiametric cells with well-defined walls and a compact tissue organisation.

In affected fruit, the outer mesocarp shows pronounced disorganisation, with deformed or collapsed cells, increased intercellular spaces and loss of the compact architecture observed in the control.

At the epidermis–cuticle interface, undulations and localised partial detachments between the cuticle and the underlying cell wall can be observed, a pattern consistent with discontinuities that could facilitate localised water ingress (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Transverse histological sections of healthy ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry (A, C, E) and fruit affected by aqueous spot (B, D, F). (A–B) Overview of the outer mesocarp (4×). (C–D) Detail of the subepidermal parenchyma (10×). (E–F) Detail of the epidermis and the epidermis–cuticle interface (20×).

Figure 3. Transverse histological sections of healthy ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry (A, C, E) and fruit affected by aqueous spot (B, D, F). (A–B) Overview of the outer mesocarp (4×). (C–D) Detail of the subepidermal parenchyma (10×). (E–F) Detail of the epidermis and the epidermis–cuticle interface (20×).

Taken together, these structural and microstructural observations indicate that aqueous spot in ‘Burlat’ should be regarded as an epidermal–subepidermal physiopathy, associated with collapse of the outer mesocarp and alterations in cuticular continuity.

This damaged architecture may constitute a predisposing substrate for subsequent progression of deterioration under conducive conditions, including the microbial colonisation that has been described for this disorder.

In addition to the structural and microstructural evidence, we assessed the impact of aqueous spot on the phenolic composition of ‘Burlat’ skin.

Skin extracts from visually healthy fruit were compared with extracts obtained exclusively from the lesioned area of affected fruit, with both groups selected at an equivalent commercial maturity stage.

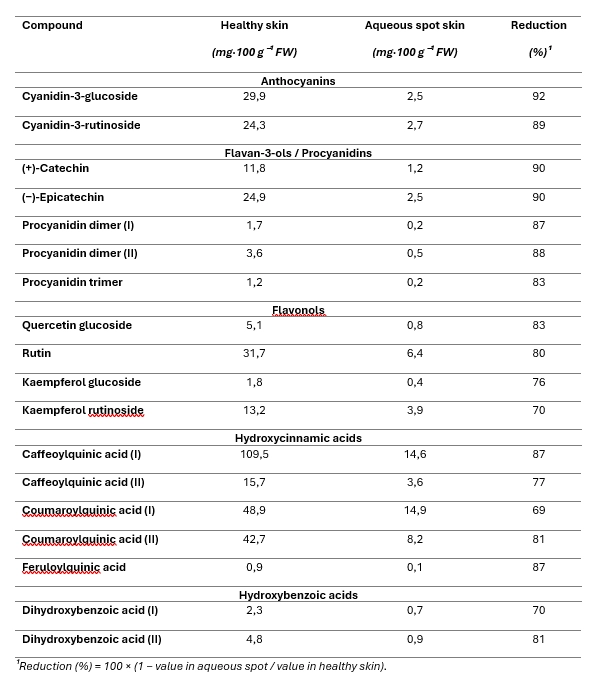

Individual compounds were quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection (HPLC–DAD), and results are expressed as mg per 100 g fresh weight (FW) of skin (Table 1).

Across compounds, the lesioned skin exhibited a pronounced depletion of phenolics relative to healthy skin (Table 1).

The largest relative decreases were observed for the major anthocyanins (cyanidin-3-glucoside and cyanidin-3-rutinoside), with concentrations in lesioned tissue reduced to a small fraction of those measured in healthy skin.

A comparable pattern was found for flavan-3-ols and procyanidins—(+)-catechin, (−)-epicatechin and their oligomers—which likewise showed marked declines (Table 1).

Hydroxycinnamic acids (caffeoylquinic and coumaroylquinic isomers, as well as feruloylquinic acid) and hydroxybenzoic acids were also substantially reduced in lesioned skin, while flavonols (rutin and quercetin- and kaempferol-glycosides) showed somewhat less extreme, yet still pronounced, decreases (Table 1).

Overall, aqueous spot is associated with a strong reduction of the phenolic pool in the affected epidermal tissue.

At the macroscopic level, this compositional shift coincides with an evident loss of pigmentation and the characteristic translucent, water-soaked appearance of the lesion (Fig. 4), consistent with the marked depletion of anthocyanins and related phenolics quantified in the lesioned skin.

Table 1. Concentration of individual polyphenols in ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry skin (mg·100 g⁻¹ FW), comparing healthy fruit with skin sampled from the lesioned area of fruit affected by aqueous spot.

Table 1. Concentration of individual polyphenols in ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry skin (mg·100 g⁻¹ FW), comparing healthy fruit with skin sampled from the lesioned area of fruit affected by aqueous spot.

Figure 4. Macroscopic comparison between a ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry fruit affected by aqueous spot (left) and a healthy fruit (right), after lifting a segment of skin from the “shoulder” region.

Figure 4. Macroscopic comparison between a ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry fruit affected by aqueous spot (left) and a healthy fruit (right), after lifting a segment of skin from the “shoulder” region.

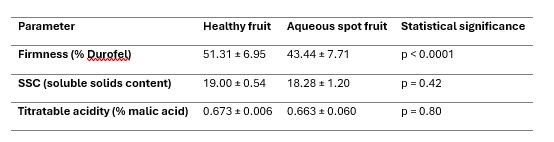

The comparison between healthy ‘Burlat’ fruit and fruit affected by aqueous spot indicates a pronounced effect on firmness, whereas the classic indices of internal maturity are only minimally impacted (Table 2).

From a mechanical standpoint, firmness measured with a Durofel penetrometer is clearly lower in affected fruit, with an approximately 15% reduction relative to healthy fruit and highly significant differences (p < 0.0001).

This loss of resistance to deformation is consistent with the collapse of the outer mesocarp observed in histological sections and confirms that the disorder effectively compromises the structural integrity of subepidermal layers.

By contrast, soluble solids content (SSC) and titratable acidity show very similar values in healthy and affected fruit, with no significant differences.

The distributions of both parameters largely overlap, indicating that aqueous spot does not appreciably alter sugar maturity or the baseline balance of organic acids at the time of harvest.

Overall, these results place the most consistent signal of aqueous spot at the structural level (loss of firmness), rather than in a shift of the internal maturity parameters assessed.

Table 2. Quality parameters in healthy and aqueous-spot-affected ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry fruit (mean ± standard deviation).

Table 2. Quality parameters in healthy and aqueous-spot-affected ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry fruit (mean ± standard deviation).

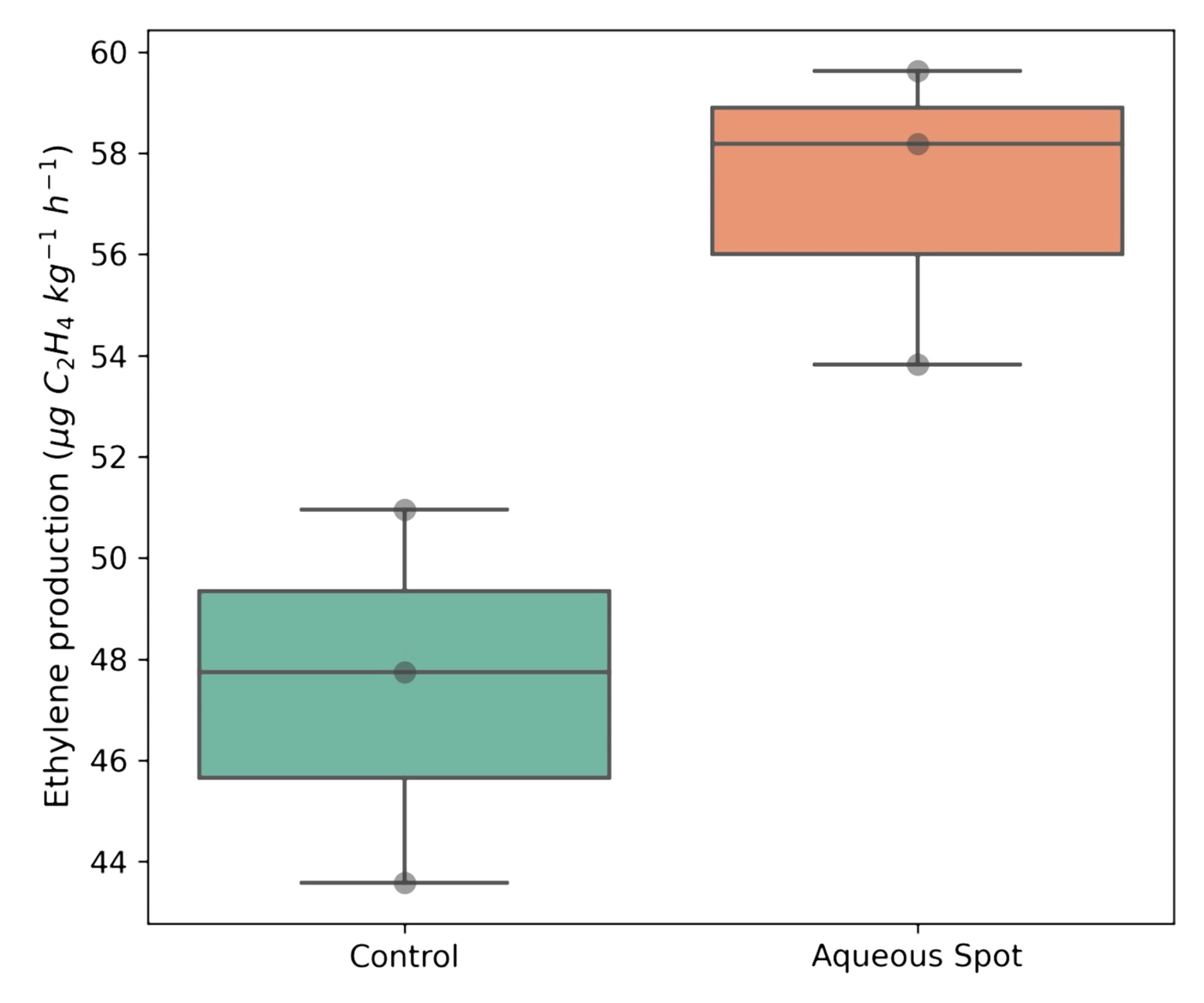

Physiological assessment focused on two key variables: respiration rate and ethylene production in healthy and aqueous-spot-affected ‘Burlat’ fruit, conditioned at 20 °C under controlled conditions.

In terms of respiration, aqueous-spot-affected fruit showed a slight increase relative to the control group (98.94 vs 91.63 mg CO₂ kg⁻¹ h⁻¹, respectively). However, within-group variability was high and the statistical comparison did not detect significant differences between groups (p = 0.57).

These results indicate that the presence of visible lesions does not necessarily translate into a uniform acceleration of respiratory metabolism across all affected fruit, but rather into heterogeneous responses within the affected lot.

By contrast, ethylene production responded clearly to the presence of aqueous spot. Affected cherries exhibited a mean production rate of 57.21 µg C₂H₄ kg⁻¹ h⁻¹, compared with 47.43 µg C₂H₄ kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ in the control group, corresponding to an increase of approximately 20%.

This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05) and was accompanied by a higher and more tightly distributed set of values in the affected group (Fig. 5), consistent with activation of pathways associated with stress and/or senescence in fruit displaying visible lesions.

Figure 5. Ethylene production in healthy (Control) and aqueous-spot-affected ‘Burlat’ sweet cherries after 24 h conditioning at 20 °C. Boxplots show the distribution of experimental values.

Figure 5. Ethylene production in healthy (Control) and aqueous-spot-affected ‘Burlat’ sweet cherries after 24 h conditioning at 20 °C. Boxplots show the distribution of experimental values.

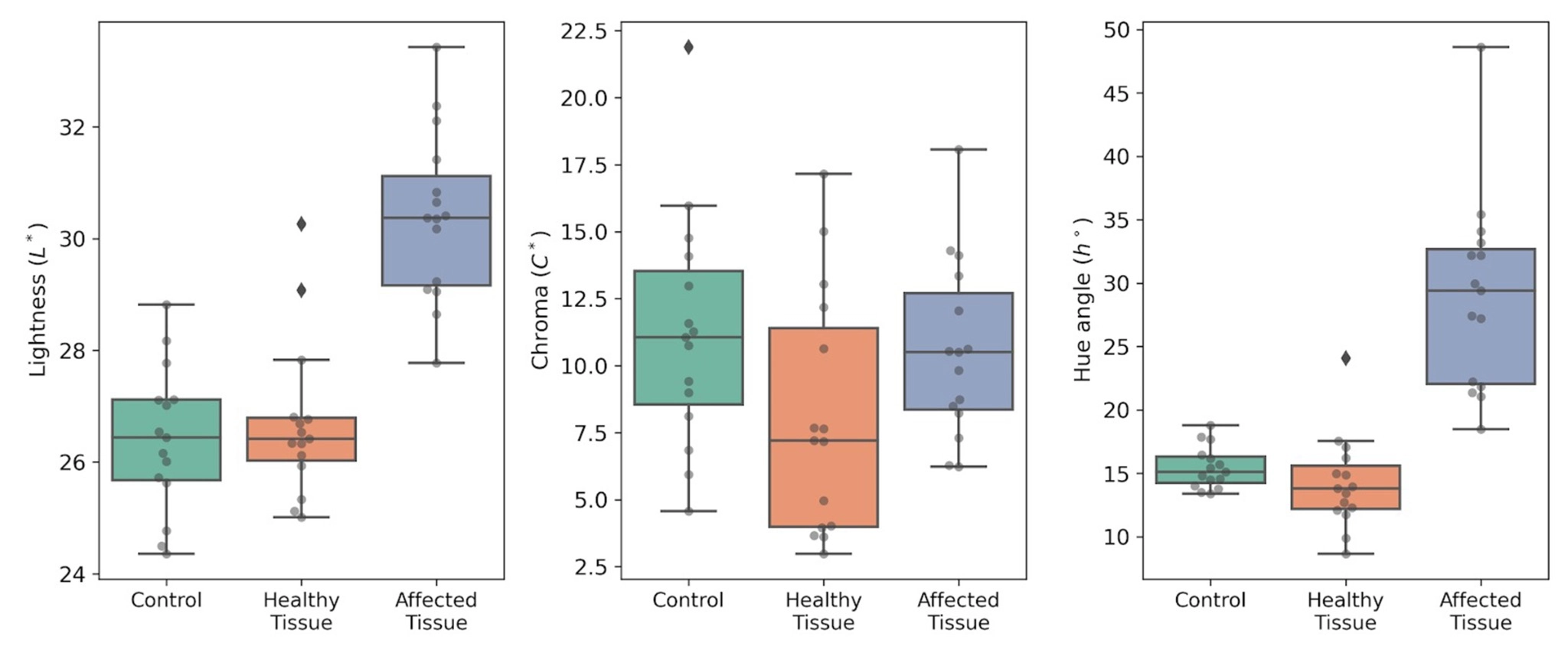

As a preliminary step before visible–NIR spectral analysis, we characterised fruit surface colour in three tissue categories in ‘Burlat’: symptom-free control fruit, visually healthy tissue on fruit displaying aqueous spot, and lesioned tissue within the affected area (Fig. 6).

Colour was quantified in the CIE LCh° space by reflectance spectrophotometry under standardised instrumental conditions.

In control fruit, L*, C* and h° values fell within the expected range for ‘Burlat’ at commercial maturity. Visually healthy tissue on aqueous-spot fruit exhibited a comparable profile, supporting the view that the disorder is not expressed uniformly across the entire epidermis, but remains confined to discrete regions of the fruit surface (Fig. 6).

By contrast, lesioned tissue showed a consistent shift in colour coordinates relative to the other two conditions (Fig. 6).

The increase in L* is consistent with the lighter, more translucent appearance of the affected area; C* tended to decrease, and h° shifted towards higher values, indicating a hue change associated with a reduction in red colour intensity.

This pattern is consistent with the macroscopic depigmentation and with the phenolic compositional changes documented above.

Overall, CIE LCh° colourimetry defines a distinct surface signature for lesioned tissue compared with both control fruit and visually healthy tissue on the same fruit (Fig. 6).

On this basis, the next step was to determine whether this optical signal is expressed concordantly in the visible–NIR spectral response, as an initial approach to non-destructive diagnosis and a prelude to subsequent hyperspectral analysis.

Figure 6. CIE LCh° colour parameters in ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry: Control fruit (Control), visually healthy tissue on aqueous-spot fruit (Healthy tissue), and lesioned tissue (Affected tissue). Left: L*; centre: C*; right: h°. Measurements were performed with a CM-3500d spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta), illuminant D65 and 10° observer.

Figure 6. CIE LCh° colour parameters in ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry: Control fruit (Control), visually healthy tissue on aqueous-spot fruit (Healthy tissue), and lesioned tissue (Affected tissue). Left: L*; centre: C*; right: h°. Measurements were performed with a CM-3500d spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta), illuminant D65 and 10° observer.

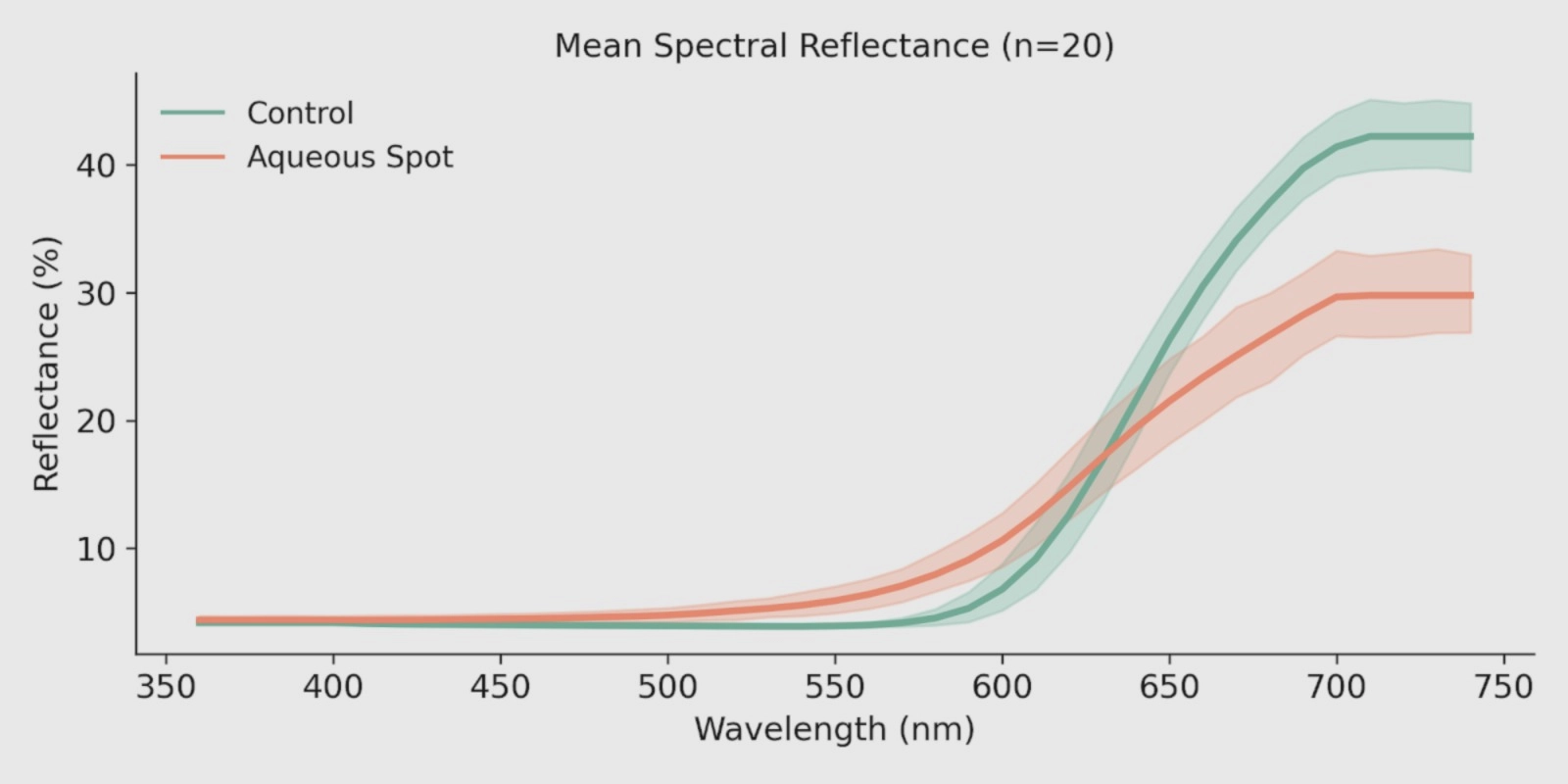

Visible reflectance spectroscopy provides a continuous description of the radiation–tissue interaction and therefore enables detection of changes driven by both pigment absorption and microstructure-dependent light scattering.

In ‘Burlat’, mean reflectance curves show a consistent separation between control fruit and fruit with aqueous spot (Fig. 7): differences are modest at shorter wavelengths, but become progressively more evident with increasing wavelength, with the affected tissue showing a distinct profile in the green–yellow region and, most notably, a differential behaviour in the red and red-edge transition.

Across this region, the spectrum of lesioned tissue exhibits an altered slope and an attenuated response relative to the control, a pattern consistent with reduced effective absorption associated with red pigmentation and concomitant changes in the scattering component of the tissue.

This behaviour is consistent with the subepidermal alteration described above.

Figure 7. Mean visible reflectance spectra (360–740 nm) in control and aqueous-spot-affected ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry (n = 10). Measurements were performed with a CM-3500d spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta), illuminant D65 and 10° observer. Shaded bands indicate measurement variability.

Figure 7. Mean visible reflectance spectra (360–740 nm) in control and aqueous-spot-affected ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry (n = 10). Measurements were performed with a CM-3500d spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta), illuminant D65 and 10° observer. Shaded bands indicate measurement variability.

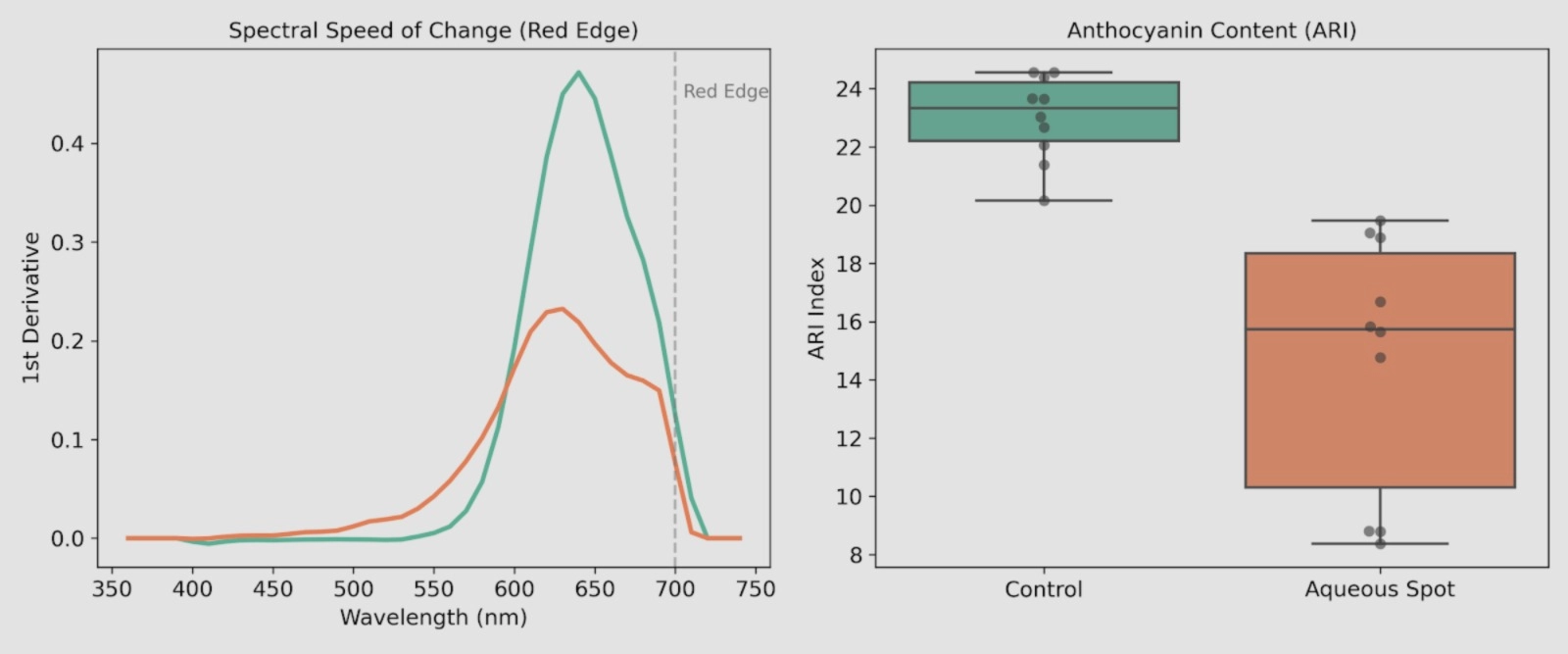

To quantify the shifts observed in the reflectance curves, we calculated (i) the first derivative of the reflectance in the red-edge region and (ii) an anthocyanin-related reflectance index (ARI), using the same measurements (Fig. 8).

In the first-derivative profiles (Fig. 8, left), the characteristic red-edge maximum is clearly more pronounced in control fruit, whereas fruit with aqueous spot shows an attenuation of this spectral gradient.

This behaviour is consistent with an altered light–tissue interaction in the lesioned area, in agreement with the differences described in the visible reflectance profile.

ARI values (Fig. 8, right) discriminate the two groups, with lower values and greater dispersion in affected fruit compared with the narrower range observed in the control.

Taken together, these results are consistent with the reduction in red colour intensity evidenced by colourimetry and with the depletion of anthocyanins documented previously in the chemical analysis of the skin.

Figure 8. Left: first derivative of reflectance in the red-edge region in ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry (Control vs aqueous spot). Right: ARI values calculated for each individual fruit in both groups. Measurements were performed with a CM-3500d spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta), illuminant D65 and 10° observer.

Figure 8. Left: first derivative of reflectance in the red-edge region in ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry (Control vs aqueous spot). Right: ARI values calculated for each individual fruit in both groups. Measurements were performed with a CM-3500d spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta), illuminant D65 and 10° observer.

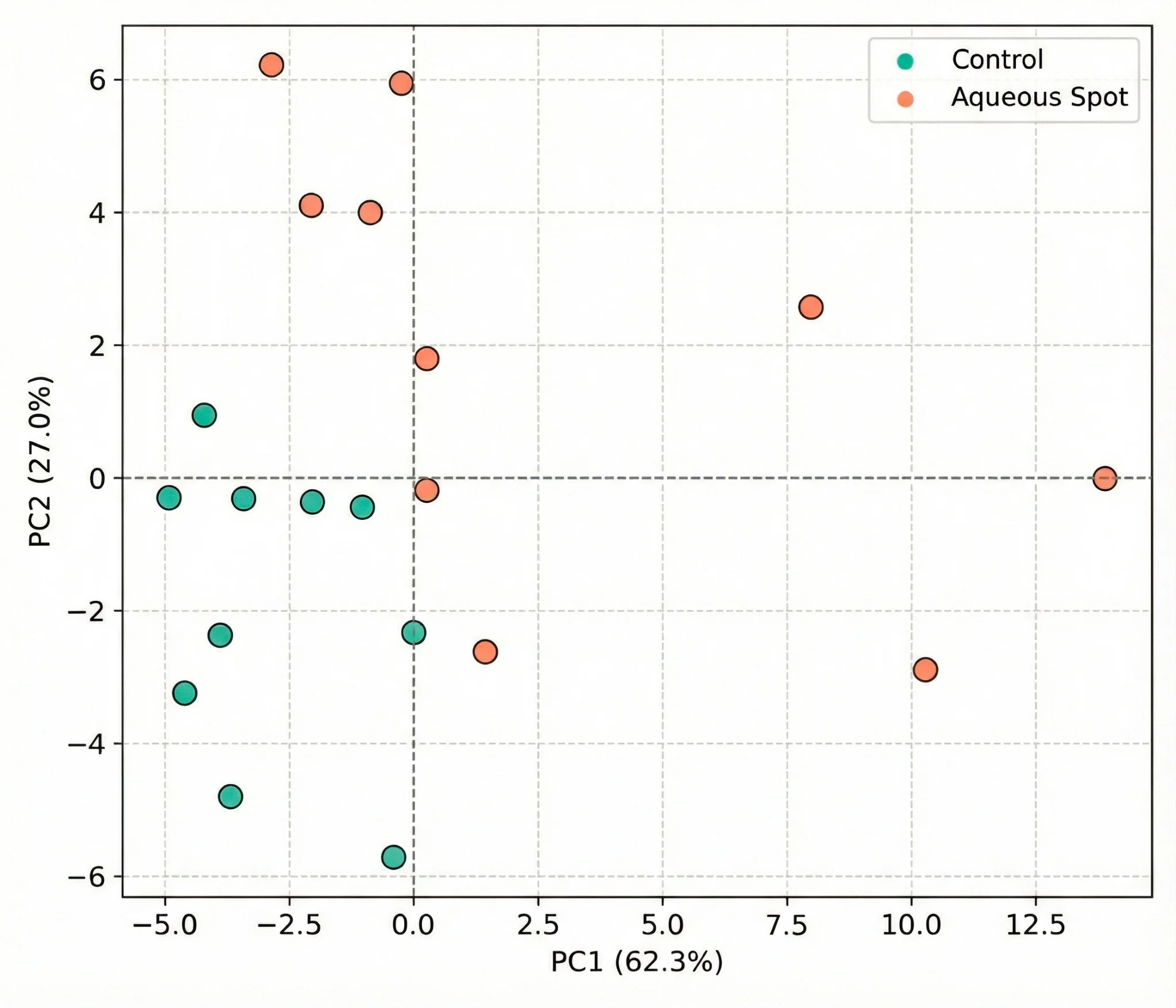

To evaluate whether the visible-range signal contains sufficient information to discriminate control fruit from fruit affected by aqueous spot, principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to the full set of spectra (n = 20).

The first two components capture the majority of system variance, and the PC1–PC2 scores plot shows a consistent separation between the two groups (Fig. 9).

Control fruit cluster within a relatively compact region of the multivariate space, whereas affected fruit are systematically displaced from this domain, reflecting a distinct spectral pattern.

These results indicate that aqueous spot is associated with an optical fingerprint that can be captured by visible-range spectrometry under controlled conditions.

Given the exploratory nature of the trial and the sample size, the operational relevance of this separation requires further validation under conditions incorporating campaign-to-campaign variability, maturity, lesion severity and measurement geometry.

Nevertheless, the observed pattern is consistent with the use of optical tools—instrumental colourimetry, spectrophotometry or, at a later stage, hyperspectral imaging—as a non-destructive approach for objective discrimination of this physiopathy.

Figure 9. PCA scores plot derived from visible reflectance spectra (360–740 nm) in ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry, comparing control fruit and fruit affected by aqueous spot in the PC1–PC2 plane. Measurements were performed with a CM-3500d spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta), illuminant D65 and 10° observer.

Figure 9. PCA scores plot derived from visible reflectance spectra (360–740 nm) in ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry, comparing control fruit and fruit affected by aqueous spot in the PC1–PC2 plane. Measurements were performed with a CM-3500d spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta), illuminant D65 and 10° observer.

Measurements obtained with the CM-3500d indicate that aqueous spot in ‘Burlat’ is associated with a consistent optical signal in the visible range (360–740 nm), sufficient to discriminate control and affected fruit by multivariate analysis.

To test whether this pattern is retained when instrumentation is changed and the spectral window is broadened, two additional trials were conducted using portable fibre-optic spectrometers: one spanning the broad visible range (190–900 nm) and a second in the short-wave NIR (900–1700 nm).

In both cases, point measurements were acquired on the fruit surface using geometries and instruments different from those employed in the initial colourimetry/spectrophotometry.

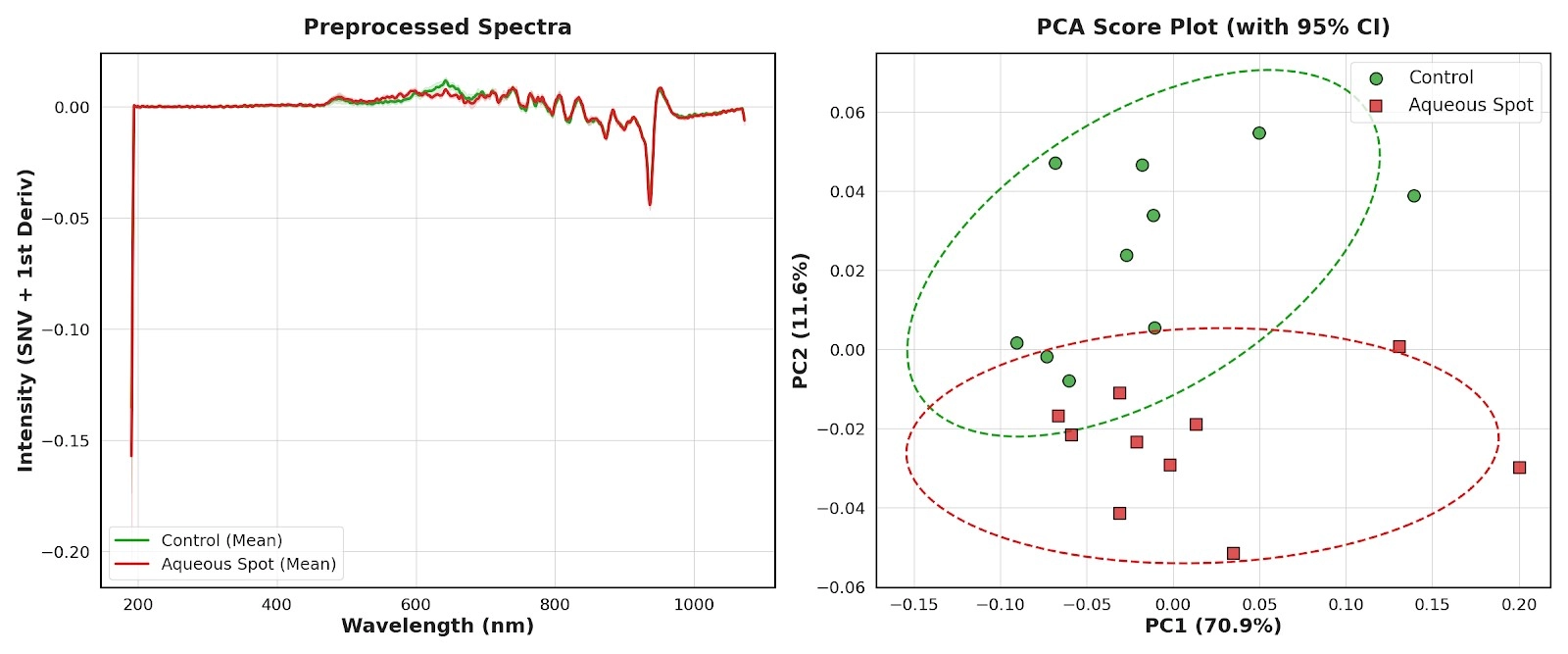

The BLACK-Comet spectrometer was used to acquire spectra over 190–900 nm in an independent set of fruit (control and aqueous spot).

After preprocessing by standard normal variate (SNV) correction and first-derivative transformation, the mean spectra display systematic differences between groups, with particularly strong contrast in the red region, while background components are attenuated by the preprocessing itself (Fig. 10, left).

Principal component analysis (PCA) summarises this difference consistently: the PC1–PC2 scores plot shows two separated clouds, with 95% confidence ellipses exhibiting only limited overlap (Fig. 10, right).

This indicates that the optical pattern associated with aqueous spot is preserved when the instrument is changed and the spectral range is extended towards the ultraviolet and the far-red.

Figure 10. Left: mean preprocessed spectra (SNV + first derivative) acquired with the BLACK-Comet spectrometer (190–900 nm) in ‘Burlat’, comparing control fruit and fruit affected by aqueous spot. Right: PCA scores plot for the same spectra, with 95% confidence ellipses (n = 10).

Figure 10. Left: mean preprocessed spectra (SNV + first derivative) acquired with the BLACK-Comet spectrometer (190–900 nm) in ‘Burlat’, comparing control fruit and fruit affected by aqueous spot. Right: PCA scores plot for the same spectra, with 95% confidence ellipses (n = 10).

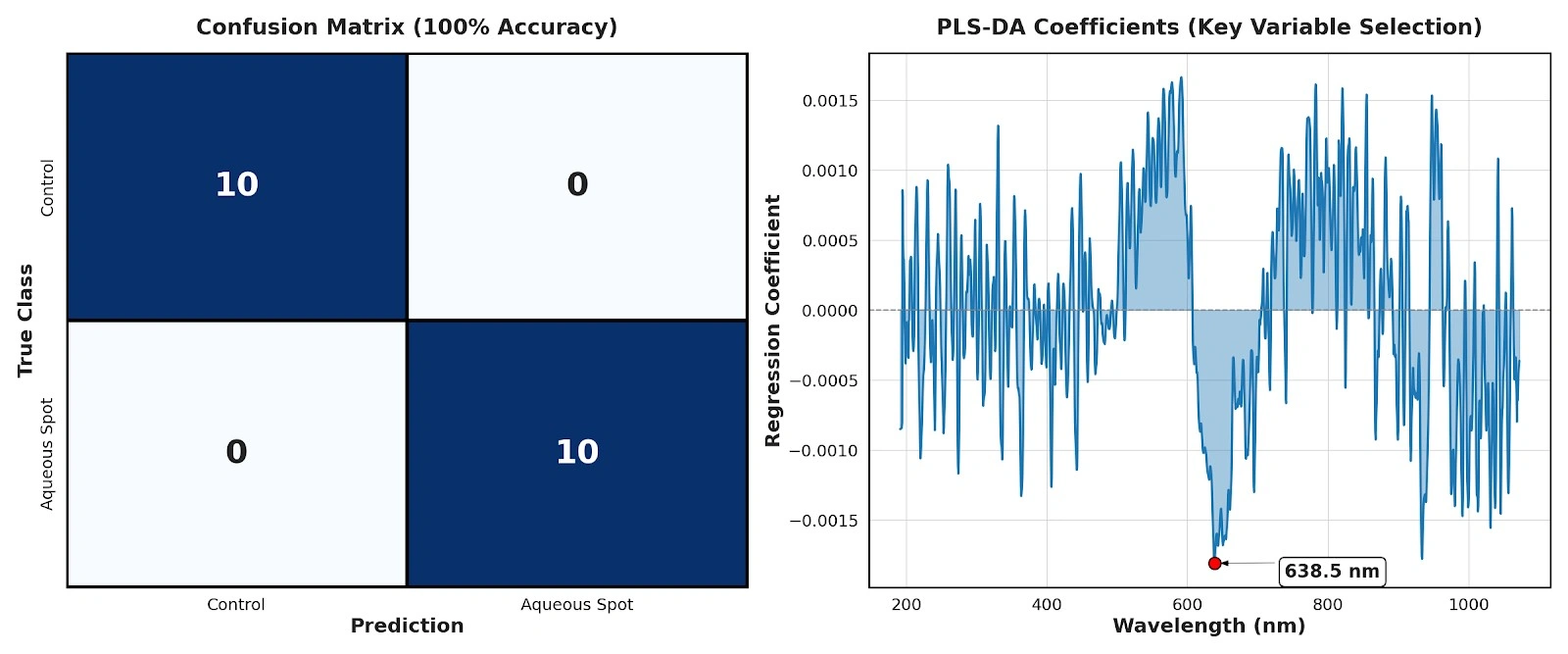

On this basis, a supervised PLS-DA model was fitted to classify control fruit versus aqueous-spot-affected fruit.

Using only two latent variables, leave-one-out cross-validation yielded 100% classification accuracy, with no misassignments between classes (Fig. 11, left).

Within the context of this dataset and measurement geometry, the result indicates that the spectral pattern associated with the disorder carries sufficient discriminant information for robust classification over 190–900 nm.

Inspection of the PLS-DA regression coefficients further allows the spectral regions contributing most strongly to discrimination to be identified.

The largest absolute contribution occurs around 638.5 nm (Fig. 11, right), within the red region of the spectrum.

From a physiological perspective, this interval is closely linked to absorption by epidermal pigments, particularly anthocyanins and other coloured phenolic compounds.

The dominant contribution of this band is consistent with the loss of pigmentation evidenced by colourimetry and with the anthocyanin depletion quantified in the chemical analysis, and suggests that the red region concentrates a substantial fraction of the optical signal associated with aqueous spot.

Figure 11. Left: confusion matrix of the PLS-DA model based on broad-band visible spectra (190–900 nm) under leave-one-out cross-validation. Right: PLS-DA regression coefficients as a function of wavelength, highlighting the region of maximal contribution around 638.5 nm.

Figure 11. Left: confusion matrix of the PLS-DA model based on broad-band visible spectra (190–900 nm) under leave-one-out cross-validation. Right: PLS-DA regression coefficients as a function of wavelength, highlighting the region of maximal contribution around 638.5 nm.

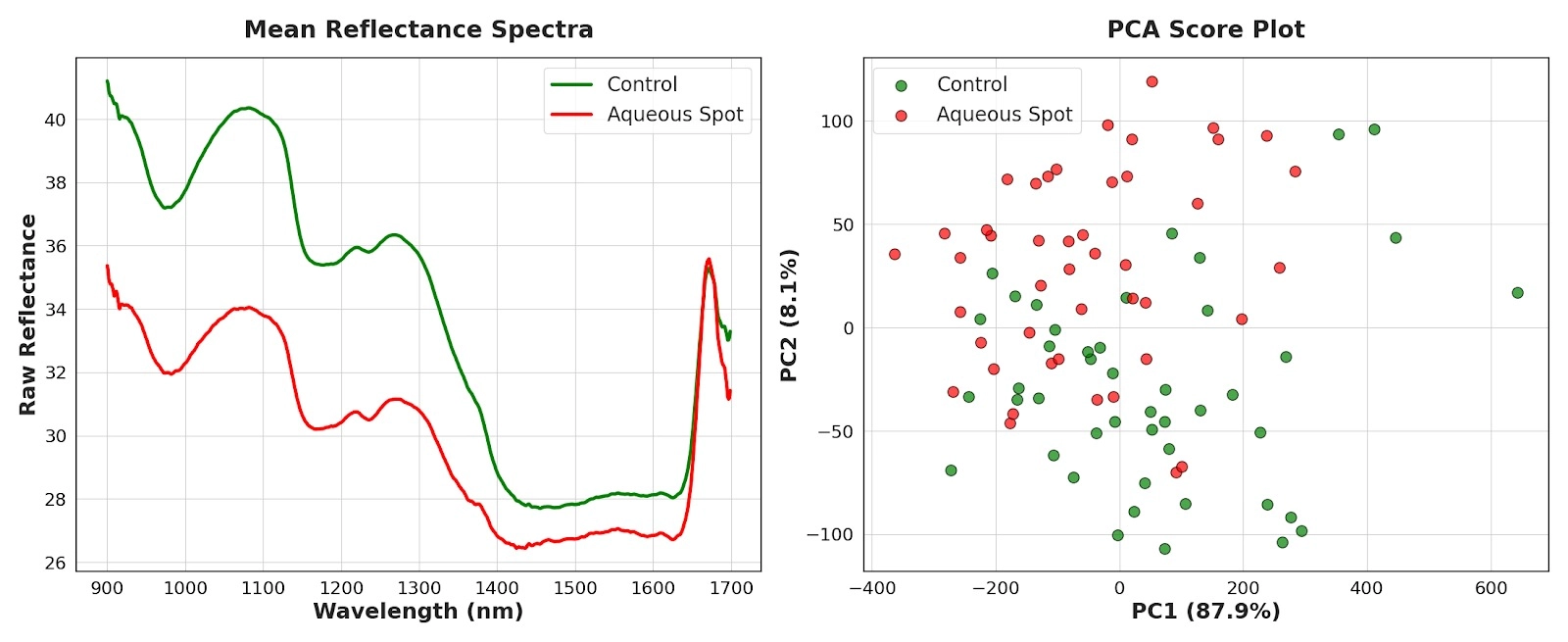

The third trial was conducted in the short-wave NIR using a portable DWARF-Star spectrometer, with the aim of assessing whether aqueous spot in ‘Burlat’ is accompanied by an optical signature compatible with changes in tissue water status and/or internal optical properties.

In this case, an expanded sample set was analysed (n = 45) and raw reflectance spectra were used in order to retain magnitude information potentially linked to the water-soaking phenotype.

Mean reflectance curves showed a stable pattern: across most of the 900–1700 nm interval, fruit affected by aqueous spot exhibited lower reflectance values than the control group (Fig. 12, left).

This systematic decrease is consistent with increased effective absorption and/or concomitant changes in internal scattering, two components that in the NIR are strongly modulated by water and by microstructural organisation.

Principal component analysis (PCA) summarised this difference clearly: the first component captured the majority of variance, and the scores plot reflected a gradient dominated by spectral magnitude, with a marked separation between control and affected fruit (Fig. 12, right).

Overall, the NIR captures a global signal consistent with an altered physical state of the tissue in the affected area.

Figure 12. Left: mean raw reflectance spectra in the NIR (900–1700 nm) for control and aqueous-spot-affected ‘Burlat’ sweet cherries (DWARF-Star). Right: corresponding PCA scores plot (PC1–PC2).

Figure 12. Left: mean raw reflectance spectra in the NIR (900–1700 nm) for control and aqueous-spot-affected ‘Burlat’ sweet cherries (DWARF-Star). Right: corresponding PCA scores plot (PC1–PC2).

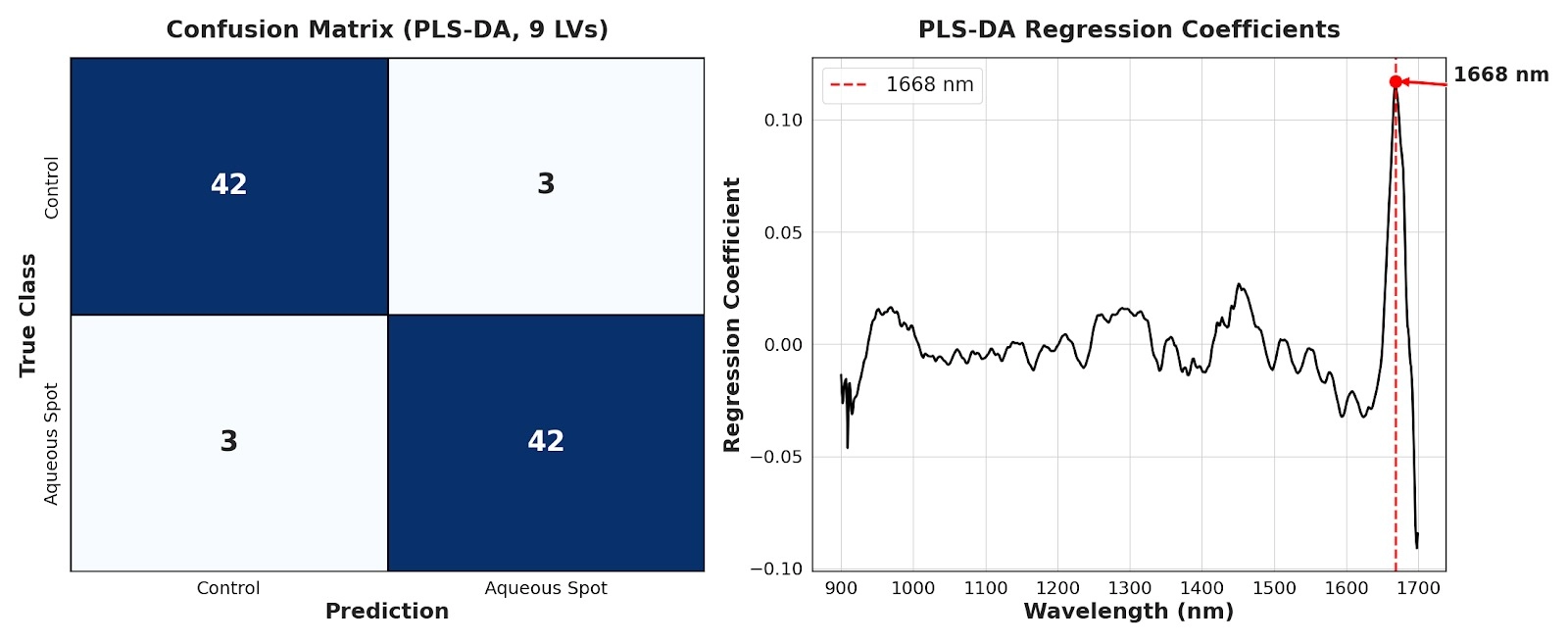

Based on these data, a PLS-DA model was fitted and optimised by cross-validation, yielding high classification performance with a limited number of errors and no obvious bias towards either class (Fig. 13, left).

Residual misclassifications are compatible with the expected heterogeneity in lesion expression/severity and partial overlap between conditions.

Inspection of the PLS-DA regression coefficients identified a dominant contribution around 1668 nm (Fig. 13, right).

This region of the NIR is commonly sensitive to combination/overtone bands involving O–H bonds; accordingly, its prominence is consistent with a component related to the state and distribution of water in the outer mesocarp, in line with the water-soaking phenotype and the tissue collapse described above.

Figure 13. Left: confusion matrix of the PLS-DA model based on NIR spectra (900–1700 nm) for control versus aqueous-spot-affected fruit. Right: PLS-DA regression coefficients, highlighting the region of maximal contribution around 1668 nm.

Figure 13. Left: confusion matrix of the PLS-DA model based on NIR spectra (900–1700 nm) for control versus aqueous-spot-affected fruit. Right: PLS-DA regression coefficients, highlighting the region of maximal contribution around 1668 nm.

Taken together, the three analytical layers—CIE LCh° colourimetry, visible spectroscopy, and broad-band visible/NIR spectroscopy—converge on a coherent framework for interpreting aqueous spot in ‘Burlat’.

In the affected area, we observe: (i) a shift in colour space towards reduced red intensity, characterised by increased lightness, lower chroma and a hue displacement; (ii) a modification of the visible spectral profile, with attenuation of the red-edge gradient and changes in the green–yellow region, consistent with a reduced effective contribution of anthocyanins; and (iii) a systematic decrease in raw short-wave NIR reflectance, consistent with altered tissue water status and internal optical properties within the lesioned zone.

From a non-destructive discrimination perspective, this convergence is relevant for two reasons.

First, the broad-band visible trial indicates that a substantial fraction of the discriminant information is concentrated in the red region, around ~640 nm, which—within the experimental framework evaluated—supports the feasibility of multispectral approaches based on a limited set of bands.

Second, the NIR provides an additional signal, largely associated with O–H-sensitive regions, which can be considered complementary to the visible by capturing changes linked to tissue water status and microstructural organisation.

Nevertheless, the scope of these findings should be regarded as preliminary. Establishing the stability of the optical fingerprint will require validation across additional seasons and, critically, across other cultivars and a wider range of cultivation, maturity and measurement conditions, before considering direct translation into operational grading or sorting scenarios.

In ‘Burlat’ sweet cherry, the integrated evidence generated in this study supports aqueous spot as an epidermal–subepidermal physiopathy with a characteristic macroscopic expression and a clearly identifiable tissue substrate in the outer mesocarp.

Structural and microstructural observations indicate that the phenomenon is not confined to a superficial colour change, but involves peripheral tissue alterations consistent with loss of integrity and localised collapse, providing a physiopathological framework that is congruent with the visible progression of the lesion.

In parallel, compositional and quality characterisation shows that the affected area exhibits a marked disruption of the phenolic profile, particularly of compounds underpinning red pigmentation, and that this shift is accompanied by measurable changes in the fruit’s physico-mechanical response, with firmness emerging as the most sensitive variable among the quality parameters assessed.

At the physiological level, the ethylene-related response provides a complementary signal consistent with an altered tissue state, without necessarily implying a parallel shift in the classical internal maturity indices at the time of sampling.

From a non-destructive diagnostic perspective, the most relevant outcome is that aqueous spot is associated with a consistent optical signature in both the visible and short-wave NIR ranges.

In the visible domain, the combination of colourimetric and spectral changes—including attenuation of the red-edge transition and the behaviour of anthocyanin-linked indices—demonstrates that the lesion systematically modifies the radiation–tissue interaction, with a prominent discriminant contribution in the red region (~640 nm).

In the NIR (900–1700 nm), the overall decrease in raw reflectance and the relevance of O–H-sensitive regions (around ~1668 nm) are consistent with water- and microstructure-modulated changes in internal absorption and scattering, reinforcing the interpretation of a water-soaking-like phenotype within the affected zone.

Overall, this work delineates a coherent framework for interpreting aqueous spot in ‘Burlat’ and demonstrates that its physiopathological expression leaves a quantifiable optical signal that can be exploited, under controlled conditions, for objective discrimination between healthy and affected tissue.

The essential next step, prior to any operational extrapolation, is to establish the stability of this fingerprint across additional seasons, genotypes and measurement geometries more representative of applied settings; on this basis, subsequent hyperspectral analysis will allow evaluation not only of detection performance, but also of potential severity stratification and the generalisability of the approach.

Adaskaveg, J.E., Förster, H., Thompson, D.F. (2000). Identification and etiology of visible quiescent infections of Monilinia fructicola and Botrytis cinerea in sweet cherry fruit. Plant Disease, 84, 328–333. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.3.328 (APS Journals)

Børve, J., Sekse, L., Stensvand, A. (2000). Cuticular fractures promote postharvest fruit rot in sweet cherries. Plant Disease, 84, 1180–1184. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.11.1180 (APS Journals)

Brüggenwirth, M., Knoche, M. (2016). Mechanical properties of skins of sweet cherry fruit of differing susceptibilities to cracking. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 141, 162–168. https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.141.2.162 (journals.ashs.org)

Grimm, E., Winkler, A., Ossenbrink, M., Schlegel, H.J., Trapp, O., Knoche, M. (2019). Localized bursting of mesocarp cells triggers catastrophic fruit cracking. Horticulture Research, 6, 79. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-019-0158-7 (ScienceDirect)

Gutiérrez, C., Figueroa, C.R., Turner, A., Munné-Bosch, S., Muñoz, P., Schreiber, L., Zeisler, V., Marín, J.C., Balbontín, C. (2021). Abscisic acid applied to sweet cherry at fruit set increases amounts of cell wall and cuticular wax components at the ripe stage. Scientia Horticulturae, 283, 110097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2021.110097 (PubMed)

Knoche, M., Beyer, M., Peschel, S., Oparlakov, B., Bukovac, M.J. (2004). Changes in strain and deposition of cuticle in developing sweet cherry fruit. Physiologia Plantarum, 120, 667–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0031-9317.2004.0285.x

Knoche, M., Peschel, S. (2006). Water on the surface aggravates microscopic cracking of the sweet cherry fruit cuticle. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 131, 192–200. https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.131.2.192 (journals.ashs.org)

Peschel, S., Knoche, M. (2005). Characterization of microcracks in the cuticle of developing sweet cherry fruit. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 130, 487–495. https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.130.4.487 (ResearchGate)

Peschel, S., Knoche, M. (2012). Studies on water transport through the sweet cherry fruit surface: XII. Variation in cuticle properties among cultivars. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 137, 367–375. https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.137.5.367 (journals.ashs.org)

Quero-García, J., Letourmy, P., Campoy, J.A., Branchereau, C., Malchev, S., Barreneche, T., Dirlewanger, E. (2021). Multi-year analyses on three populations reveal the first stable QTLs for tolerance to rain-induced fruit cracking in sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.). Horticulture Research, 8, 136. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-021-00571-6 (Nature)

Serradilla, M.J., Moraga, C., Ruiz-Moyano, S., Tejero, P., Córdoba, M.G., Martín, A., Hernández, A. (2021). Identification of the causal agent of Aqueous Spot disease of sweet cherries (Prunus avium L.) from the Jerte Valley (Cáceres, Spain). Foods, 10, 2281. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10102281 (MDPI)

Weichert, H., Knoche, M. (2006). Studies on water transport through the sweet cherry fruit surface. 10. Evidence for polar pathways across the exocarp. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 54, 3951–3958. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf053220a (journals.ashs.org)

Winkler, A., Blumenberg, I., Schürmann, L., Knoche, M. (2020a). Rain cracking in sweet cherries is caused by surface wetness, not by water uptake. Scientia Horticulturae, 269, 109400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109400 (ScienceDirect)

Winkler, A., Riedel, D., Neuwald, D.A., Knoche, M. (2020b). Water influx through the wetted surface of a sweet cherry fruit: Evidence for an associated solute efflux. Plants, 9, 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9040440

Agroseguro (2025). Condiciones Especiales del Seguro de Explotaciones de Cereza. Línea 317, Plan 2025. Madrid, España. (agroseguro.es)