What is needed to identify a cherry?

According to a lengthy legal dispute between the Canadian government and some fruit companies in Washington, several forms of DNA screening, years of field experiments, and a federal judge's ruling are required.

Experts not involved in the case say that with modern genetic screening, it's not that difficult.

“It should have been discovered earlier,” said Dianne Velasco, supervisor of the plant identification laboratory for the Foundation Plant Services, a clean plant center at the University of California, Davis.

With the emergence of many new proprietary varieties, Velasco and other genetics experts state that screening should be more routine for growers and nurseries in the fruit industry. However, the process for patents and plant protections has not required the use of modern technology.

An example: In 2020, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada accused two growers and a nursery of propagating, cultivating, and selling its late-ripening Staccato cherry cultivar under a different name, Glory.

In August, after four years of hearings and testimonies that included up to eight different genetic tests and phenotypic comparisons of fruit size, bloom timing, and stem retention, a judge in the United States District Court for Eastern Washington ruled that the two cherries were indeed the same. The lawsuit continues as the parties work on other discrepancies.

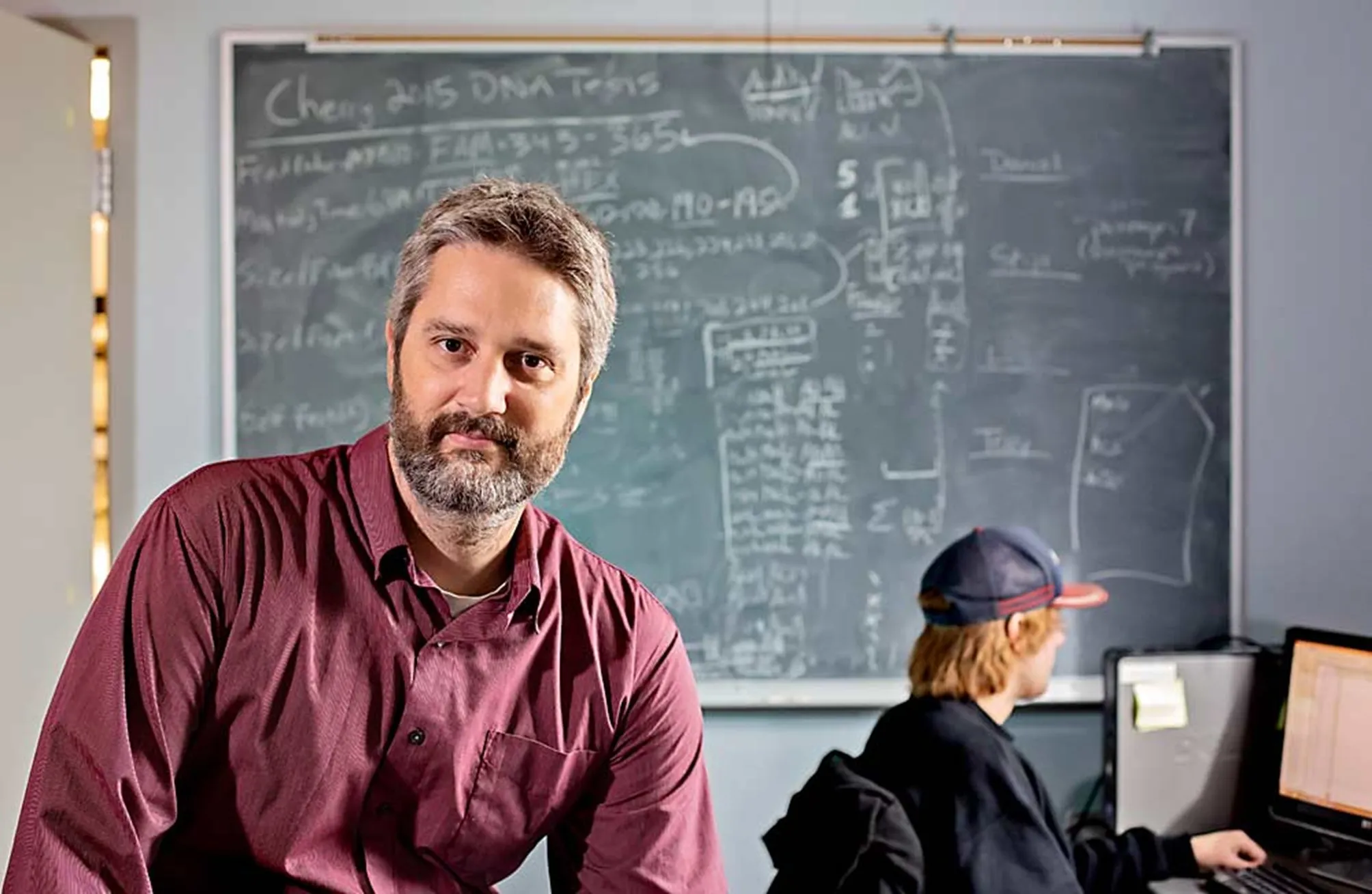

Cameron Peace, professor of fruit tree genetics at Washington State University, believes that this level of analysis, designed to win a legal battle, is excessive.

Image 1: Cameron Peace, geneticist and professor of pomology at Washington State University (USA). Source: Good Fruit Grower.

Image 1: Cameron Peace, geneticist and professor of pomology at Washington State University (USA). Source: Good Fruit Grower.

In most cases, a genotypic test—looking for small variations within the genetic code that could manifest in physical differences—should be sufficient. He suggests starting with something low-resolution and moving to higher resolution if necessary.

“If this happened in my research orchard, I would immediately dedicate myself to finding the answer,” Peace said.

But not all genetic tests are equal.

The Staccato-Glory controversy began with a grower who found an unusually late-ripening cherry in an orchard of a different variety. If it had truly been a unique, fortuitous sport, it would have given him and anyone selling the cherry an economic advantage in the late-market window.

According to court documents, the grower hired a geneticist in 2008 to compare his “new” variety, Glory, with Staccato and Sweetheart. However, that geneticist obtained inconsistent results and later admitted in court that the tests were less modern and robust than those conducted on behalf of the Canadian breeder.

Image 2: The Staccato cherry variety, developed by the Canadian government’s Summerland Research and Development Center in British Columbia. Source: World Fresh.

Image 2: The Staccato cherry variety, developed by the Canadian government’s Summerland Research and Development Center in British Columbia. Source: World Fresh.

The Canadian breeder, in turn, hired their own geneticists to perform more modern tests, a statistician to compare both sides' results, and a horticulturist to carry out five phenotypic comparison trials—assessing physical, visible differences in the plants. The two experts concluded that the two cherries were identical, and the judge agreed.

Testing Technology

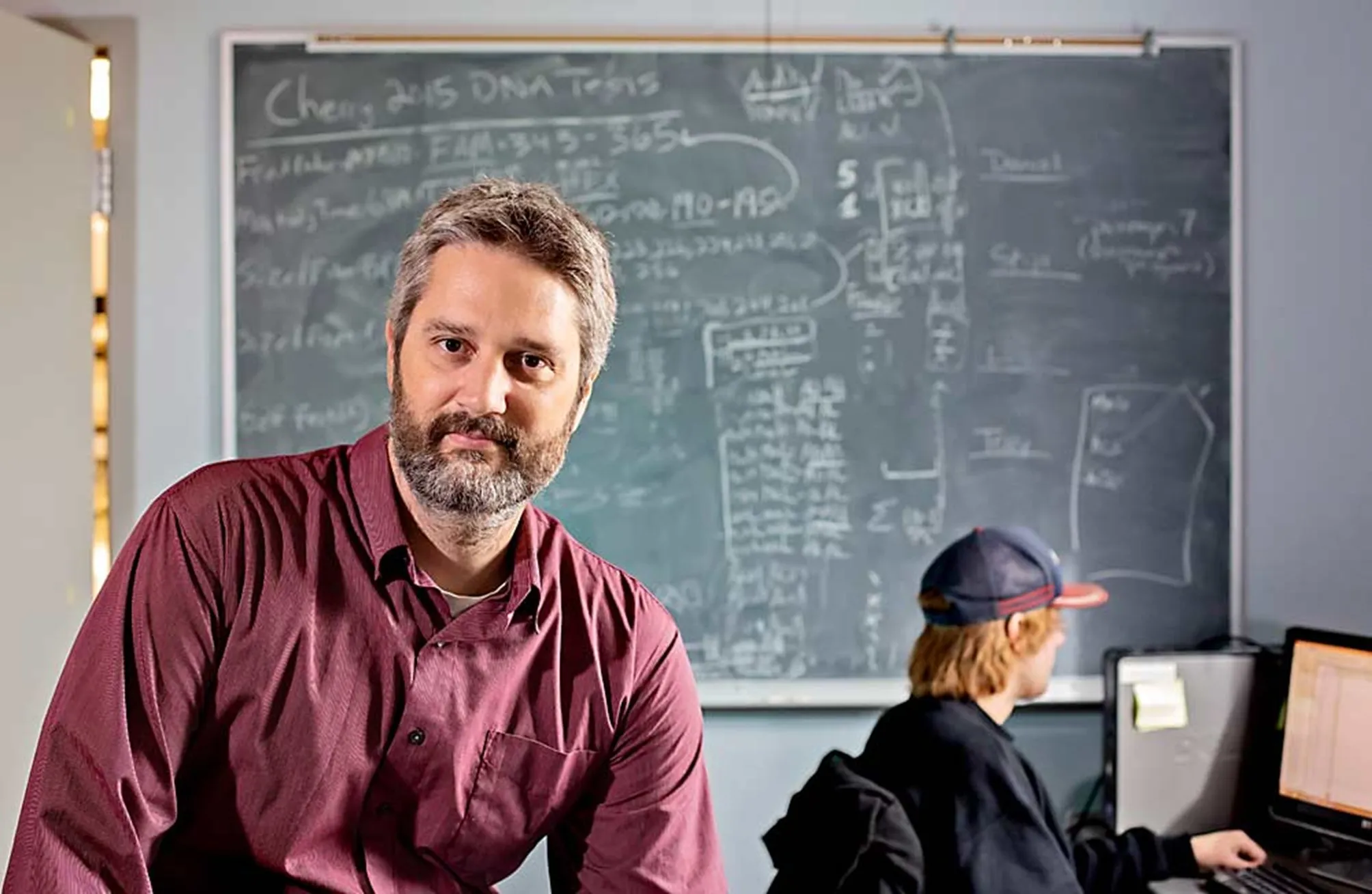

According to Peace, laboratories across the United States offer genetic screening, but not always at a scale that allows a single grower with one variety in question. Meanwhile, geneticists familiar with the crops are sometimes less available. For some crops, including cherries, the industry lacks centralized, accessible DNA reference information. There is no equivalent to a federal fingerprint database for agricultural plants.

Thanks to his work with RosBREED, a national team of scientists seeking to improve rosaceous fruit genetics, Peace conducts SNP tests, a process that searches for single nucleotide polymorphisms: small genetic variations that can distinguish individuals within the same species or cultivar. Tests on apples are done for a fee ($50) through MyFruitTree, a WSU non-profit research lab offering apple DNA fingerprinting. He sends leaf tissue samples to wet labs in Wisconsin or Florida for screening.

In return, he receives raw data that he can read and compare with known references from over 5,000 previously established apple DNA profiles.

However, most labs require minimum batches of up to 384 samples. The lab Peace uses requires 192 samples, and he receives enough requests to meet this threshold, at least for apples.

Image 3: Twelve breeding programs in RosBREED 1 and 22 breeding programs in RosBREED 2 served as “demonstration breeding programs.” Source: Nature.

Image 3: Twelve breeding programs in RosBREED 1 and 22 breeding programs in RosBREED 2 served as “demonstration breeding programs.” Source: Nature.

Cherries, due to lower demand, do not have the advantage of such a comprehensive database. Peace stopped offering cherry screening a few years ago when a critical supplier ceased producing SNP arrays for cherries—the physical equipment used for the screenings.

Foundation Plant Services in California offers small-scale screening for a price ranging from $300 to $410 per sample but currently lacks the capacity to serve the entire U.S. fruit and nut industry, Velasco said.

Her lab performs DNA tests known as simple sequence repeats, or SSR, to identify almonds, apples, apricots, cherries, olives, peaches, pistachios, plums, and walnuts, but grapes are its main focus. The lab has an internal database of approximately 1,700 unique grape profiles, while the international Vitis variety catalog, which is searchable, contains profiles for 6,350 cultivated varieties.

Both SSR and SNP tests were presented as evidence in the Staccato-Glory case.

For apples, Foundation Plant Services compares to an SSR dataset available from the United States Department of Agriculture. For cherries, however, it has only 150 profiles of varieties available in its internal database.

Image 3: Headquarters of Foundation Plant Service, UC Davis California (USA). Source: UC Davis.

Image 3: Headquarters of Foundation Plant Service, UC Davis California (USA). Source: UC Davis.

Cherries also have a narrower genetic base and therefore more similarities between varieties, Velasco said. For this reason, the service conducts screening of 15 genetic markers instead of the eight used for grapes.

Whole genome comparison (whole genome sequencing) would be prohibitive for routine identification, even though it was ultimately conducted for the Staccato litigation.

Patents

Patents do not require genetic evidence, so they do little to clarify disputes over DNA.

For a time, both Staccato and Glory had their own plant patents in the United States. At the beginning of the legal proceedings, the judge invalidated the Staccato patent due to a timing error at filing, leaving a valid patent only for Glory. Then, his subsequent decision identified Staccato as the original variety.

It’s not as absurd as it might seem, says Michelle Bos, a Zillah, Washington attorney specializing in plant patents.

“U.S. plant patents are examined only on paper,” said Bos, who helped file the patent application for the grower who thought he had discovered Glory.

U.S. plant patents, first established in 1930, require detailed written descriptions, drawings, and photographs. As the number of patented plants has grown over the years, these descriptions - called disclosures - have become longer and more detailed, but the process has never required DNA evidence.

For McCord, a cherry breeder at WSU, he is aware of the limitations of the patent system as the university prepares to potentially release up to three new unnamed cherries currently in advanced commercial testing.

“The whole patent system wasn’t created with plants in mind,” McCord said.

For the R19 cherry, the closest to release, the university has not yet decided whether to seek a plant patent from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office or request protection from the Plant Variety Protection Office of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Or both.

Image 4: McCord, cherry breeder at Washington State University (USA). Source: The Packer.

Image 4: McCord, cherry breeder at Washington State University (USA). Source: The Packer.

To prepare, McCord and the university have started meticulously recording data on bark color, leaf shape, growth habits, and other tree characteristics at different times of the year, as well as fruit traits.

According to McCord, broader use of DNA screening in orchards and nurseries could be very useful in preventing disputes before they occur, but it wouldn’t be foolproof.

The university tested the three varieties using a technique that generates 1,600 to 3,400 genetic markers. Even then, such a test might not reveal any difference between a variety and a random sport, he said.

One lesson, experts say, is that random mutations occasionally occur in fruit trees, even though they are rare. There are examples of growers unexpectedly striking gold when noticing a physical trait different enough to warrant a unique and marketable variety.

However, a simple nursery error is more common. If a tree looks different, it’s probably a different tree, mistakenly packaged with others. That’s how the Staccato-Glory dispute is believed to have started.

McCord liked the idea of conducting DNA testing early, especially when there’s confusion or doubt. “If the origin of what you have is a bit murky, I think more caution is warranted,” McCord said.

Read the full article: Good Fruit Grower

Cherry Times - All rights reserved