The cherries are non-climacteric fruits that are highly perishable, and their quality at harvest is defined by external and sensory attributes, including fruit size (caliber), color, firm texture, and skin free from blemishes, bruises, and cracks. Post-harvest deterioration is associated with a high respiration rate and the expression of the fruit's mechanical properties.

A firm texture in cherry fruits is associated with lower susceptibility to decay, greater resistance to mechanical damage from compression, and greater consumer acceptance, which helps minimize losses and ensures marketability.

Firmer cherries allow for faster processing on the lines, increasing the efficiency of the packaging process, and with it a range of post-harvest advantages, resulting in better product conditions in export markets.

The cherry is harvested at a stage close to consumption. Therefore, pre-harvest management practices are essential to obtain a product with the quality required for the destination market and the conditions to withstand the post-harvest period, from harvest to sorting, packaging, transport to the destination, distribution to the destination market, and shelf life.

The interaction of multiple factors during the pre-harvest handling of the crop explains its behavior at harvest, which makes agronomic practices fundamental tools to bridge the quality gaps caused by the pedoclimatic factors to which the cherry tree is exposed.

Among these practices is foliar nutrition with calcium (Ca) and the possibility of integrating its low availability in the fruit. This practice, used in other fruit species, is often questioned due to its low effectiveness.

The foliar application of Ca in cherries has been recommended mainly to reduce cracking and increase firmness of the fruits; however, its efficiency and its actual effects in relation to other management practices are debated. Therefore, through a research project at the Faculty of Agronomy and Natural Systems of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, we studied the usefulness and impact of aerial Ca applications on fruit firmness and mechanical properties.

This article summarizes some results on the use of foliar Ca in cherries.

Development Stage for Foliar Calcium Applications

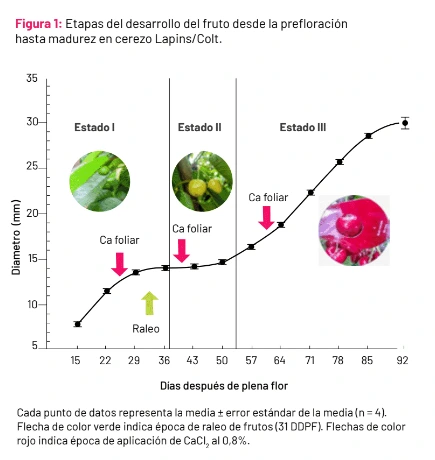

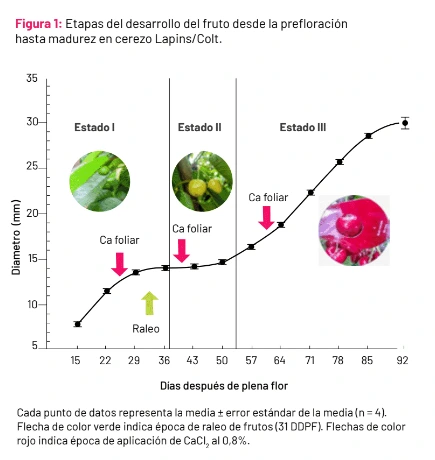

In an initial study, the interaction between foliar applications of calcium chloride (CaCl2) and the load level in the Lapins/Colt combination was evaluated, conducted at Kym Green Bush (KGB). The 0.8% foliar CaCl2 was applied during stages I (cell division), II (pit hardening), and III (accelerated growth) of fruit development (Figure 1), considering trees with 100% (21 kg/tree) and 50% (12 kg/tree) of the seasonal load.

Figure 1: Fruit development stages from pre-bloom to maturity in Lapins/Colt cherry trees. Each data point represents the mean +/- standard error of the mean (n=4). The green arrow indicates the fruit thinning period (31 DDPF). Red arrows indicate the period of 0.8% CaCl₂ application.

Figure 1: Fruit development stages from pre-bloom to maturity in Lapins/Colt cherry trees. Each data point represents the mean +/- standard error of the mean (n=4). The green arrow indicates the fruit thinning period (31 DDPF). Red arrows indicate the period of 0.8% CaCl₂ application.

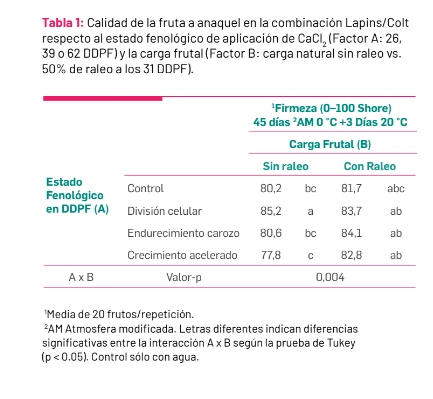

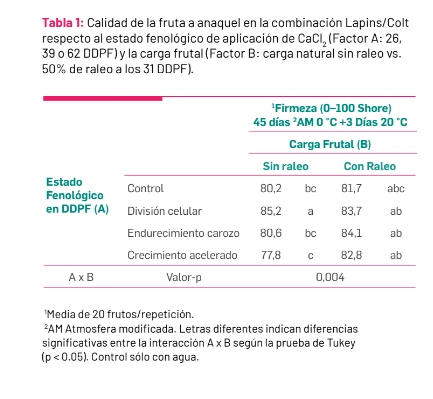

In non-thinned trees (100% load), a foliar application of CaCl2 during the cell division period increased fruit firmness at harvest, and its effect remained after 40 days at 0°C and 3 days at 20°C, compared to applications during pit hardening and accelerated growth after veraison (Table 1).

Table 1: Fruit quality in the Lapins/Colt combination in relation to the phenological stage of CaCl₂ application (Factor A: 26, 39, or 62 DDPF) and fruit load (Factor B: natural load without thinning vs. 50% thinning at 31 DDPF). 1 - Average of 20 fruits per repetition. 2 - Modified atmosphere (AM). Different letters indicate significant differences in the A x B interaction according to the Tukey test (p<0.05). Control with water only.

Table 1: Fruit quality in the Lapins/Colt combination in relation to the phenological stage of CaCl₂ application (Factor A: 26, 39, or 62 DDPF) and fruit load (Factor B: natural load without thinning vs. 50% thinning at 31 DDPF). 1 - Average of 20 fruits per repetition. 2 - Modified atmosphere (AM). Different letters indicate significant differences in the A x B interaction according to the Tukey test (p<0.05). Control with water only.

However, subsequent applications of CaCl2 reduced the incidence of induced cracking in thinned trees (see Table 2). This demonstrates the higher incidence of cracks in thinned trees and the importance of subsequent applications to reduce this increased sensitivity.

Table 2: Interaction between the phenological stage of foliar CaCl₂ application at 0.8% (Factor A: 26, 39, or 62 DDPF) and fruit load (Factor B: natural load without thinning vs. 50% thinning at 31 DDPF) on the cracking index of Lapins/Colt cherries.

Table 3: Fruit Ca concentration at harvest (91 DDPF) in response to different foliar treatments with CaCl₂ (Control = 0%; 0.2%; 0.4% and 0.8%), applied at 23 DDPF in the Lapins/Colt combination.

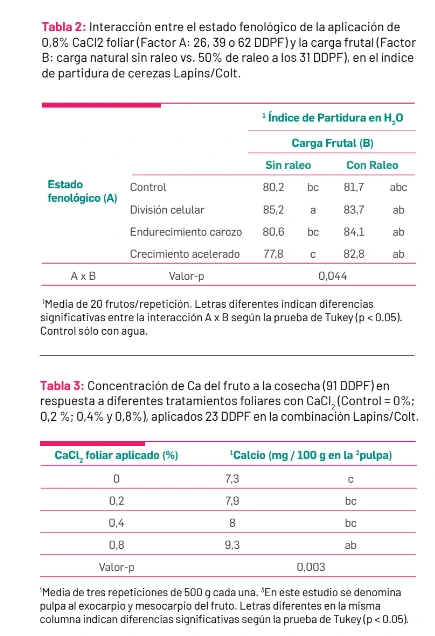

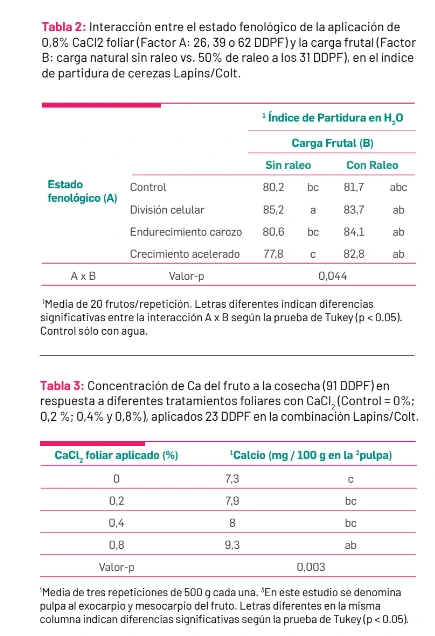

On the other hand, analyzing the natural concentrations of Ca in the fruit, it was observed that accumulation begins early and decreases as maturation progresses, indicating a period of higher concentration in the early stages and then dilution due to growth and probably also due to lower translocation into the fruit (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Evolution of Ca concentration and content in fruits of trees with 100% of the natural fruit load and without foliar applications of CaCl₂ in the Lapins/Colt combination.

Figure 2: Evolution of Ca concentration and content in fruits of trees with 100% of the natural fruit load and without foliar applications of CaCl₂ in the Lapins/Colt combination.

Calcium concentration via foliar application

The results of the first study highlighted the need to understand the relationship between the application of CaCl2 via foliar spraying at stage I of fruit growth and the aspects of fruit condition in post-harvest. To this end, we worked again with the Lapins/Colt combination, using incremental concentrations of CaCl2 (Control = 0%; 0.2%; 0.4%; 0.8% and 1.6%) during the cell division phase.

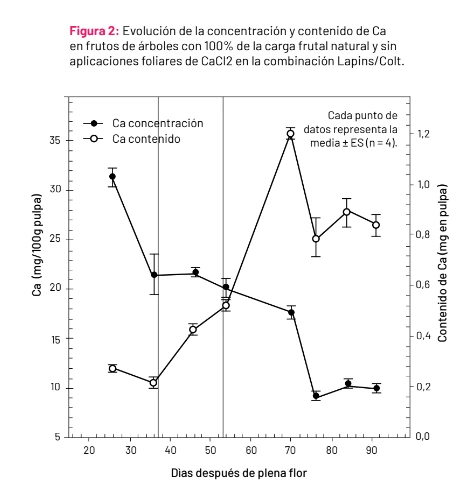

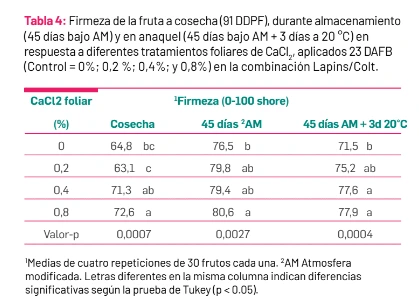

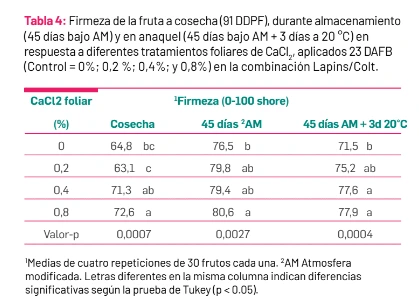

The highest levels of Ca in the fruit (Table 3) and the greatest firmness at harvest and during storage were observed for concentrations greater than 0.8% (Table 4). Increasing the Ca concentration in the fruit improved the tissue resistance and post-harvest conditions, but did not significantly improve tissue deformability enough to avoid the increased sensitivity to russeting induced in the fruit. In fact, the incidence of russeting increased by 82% with the application of 0.8% CaCl2.

Table 4: Fruit firmness at harvest (91 DDPF), during storage (45 days under modified atmosphere), and on shelf (45 days under modified atmosphere + 3 days at 20°C) in response to different foliar treatments with CaCl₂, applied at 23 DAFB (Control = 0%; 0.2%; 0.4% and 0.8%) in the Lapins Colt combination.

Table 4: Fruit firmness at harvest (91 DDPF), during storage (45 days under modified atmosphere), and on shelf (45 days under modified atmosphere + 3 days at 20°C) in response to different foliar treatments with CaCl₂, applied at 23 DAFB (Control = 0%; 0.2%; 0.4% and 0.8%) in the Lapins Colt combination.

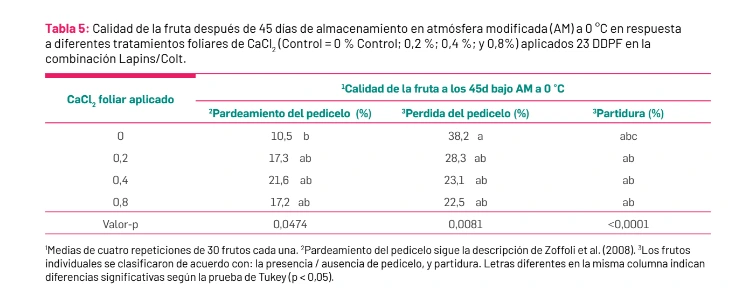

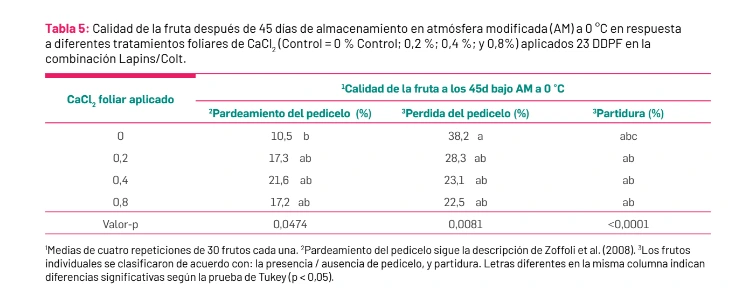

Significant positive linear relationships were found between the Ca concentration in the pulp, the mechanical properties of the fruit, and the damage index, resulting in a cherry with less softening, but more fragile to impact damage. Moreover, foliar treatments with CaCl2 showed a reduction in the incidence of cracking and pedicel detachment after 45 days at 0°C.

However, an increase in the percentage of fruits with pedicel browning was observed for the highest concentration of foliar CaCl2 (1.6%) (Table 5), which sets a limit on the concentration to use. Therefore, in Tables 3, 4, and 5, the 1.6% concentration is discarded due to the harmful effect of pedicel browning. Finally, it is essential to monitor fruit growth (size and weight) and pedicel condition in each variety, as the incidence of browning and the fruit behavior vary greatly depending on it.

Table 5: Fruit quality after 45 days of storage in modified atmosphere (MA) at 0°C in response to different foliar treatments with CaCl₂ (Control = 0%; 0.2%; 0.4% and 0.8%) applied at 23 DDPF in the Lapins Colt combination.

Table 5: Fruit quality after 45 days of storage in modified atmosphere (MA) at 0°C in response to different foliar treatments with CaCl₂ (Control = 0%; 0.2%; 0.4% and 0.8%) applied at 23 DDPF in the Lapins Colt combination.

Based on this, it is concluded that the foliar application of CaCl2 during phase I of fruit development (cell division) should be between 0.6 and 0.8% to achieve an increase in the Ca concentration in the pulp. It is important to note that the Ca concentration in the control fruits (without foliar Ca application) was below 10 mg/100g.

The foliar calcium pathway

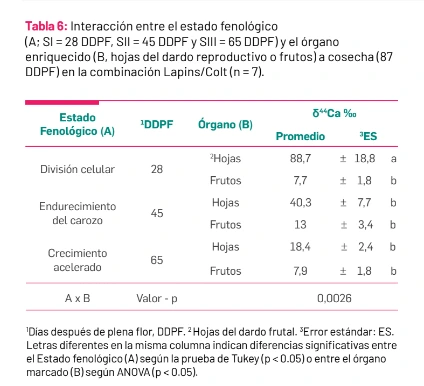

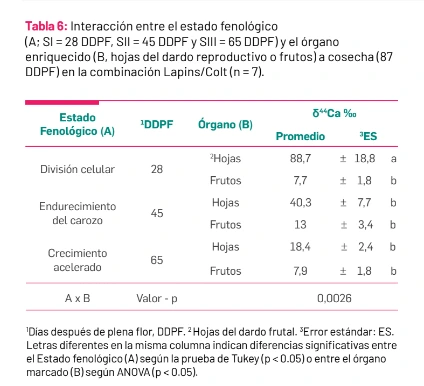

Finally, we wanted to clarify whether the leaves or the fruits differ in their ability to absorb Ca depending on the phenological stage when the foliar application of CaCl2 was made. To detect the differences in absorption and distribution of Ca, we worked with the stable isotope 44Ca (labeled with Ca). The leaves or fruits were painted with a brush (photo 2) during fruit development.

The results showed that both the fruits and the leaves absorbed the labeled Ca throughout the fruit development period, although the Ca footprint varied depending on the application time and the sampling date (Table 6). In general, the leaves of the reproductive shoots showed higher concentrations of labeled Ca compared to the fruits.

Table 6: Interaction between phenological stage (A; SI = 28 DDPF, SII = 45 DDPF, and SIII = 65 DDPF) and the enriched organ (B, reproductive shoot leaves or fruits) at harvest (87 DDPF) in the Lapins/Colt combination (n=7).

Table 6: Interaction between phenological stage (A; SI = 28 DDPF, SII = 45 DDPF, and SIII = 65 DDPF) and the enriched organ (B, reproductive shoot leaves or fruits) at harvest (87 DDPF) in the Lapins/Colt combination (n=7).

The younger the leaves and fruits, the higher the concentration of labeled Ca found in the tissues. Therefore, it is concluded that foliar Ca is absorbed by both leaves and fruits, with a predominance of leaves, and the absorption is more efficient in younger fruits and leaves.

Conclusions

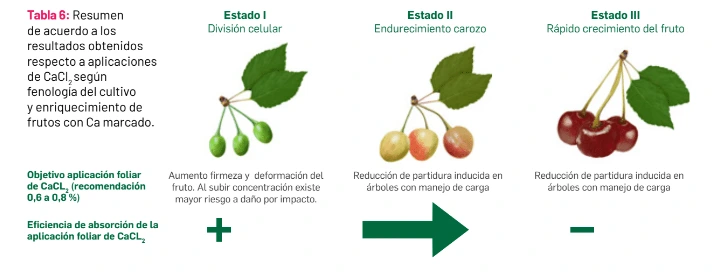

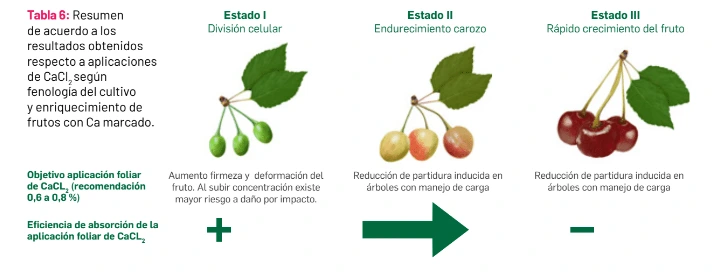

Based on the results, we can state that for the Lapins cultivar, the timing and dosing of the Ca application, in the form of calcium chloride, are important to increase the efficiency of foliar absorption (aerial). The earlier the foliar application of Ca, the greater the amount of Ca recovered in the leaves and fruits.

Most of the absorption occurs from the leaves, especially during the cell division period, with doses between 0.6 and 0.8% of calcium chloride. On the other hand, foliar Ca applications early in fruit development will be more effective in increasing fruit firmness, while later in the season they will reduce the percentage of fruit cracking (Figure 3).

Image 3: Summary of results regarding CaCl₂ applications based on crop phenology and fruit enrichment with labeled Ca.

Image 3: Summary of results regarding CaCl₂ applications based on crop phenology and fruit enrichment with labeled Ca.

Source: Mundoagro

Images: Mundoagro

Marlene Ayala, Maritza Matteo, Juan Pablo Zoffoli

Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile

Cherry Times - All rights reserved