The vibrant colors of fruits—from the deep red of ripe cherries to the bright yellow or purple of other fruits—have long fascinated humans.

But what processes truly determine these chromatic differences? Why do some fruits develop very dark tones while others remain lighter?

Although it is well known that anthocyanins, a class of plant compounds also beneficial to health, are the main contributors to the red, blue, and purple hues of fruit skin and flesh, the genetic mechanisms regulating their synthesis are not yet fully understood.

Fruit color and genetic factors

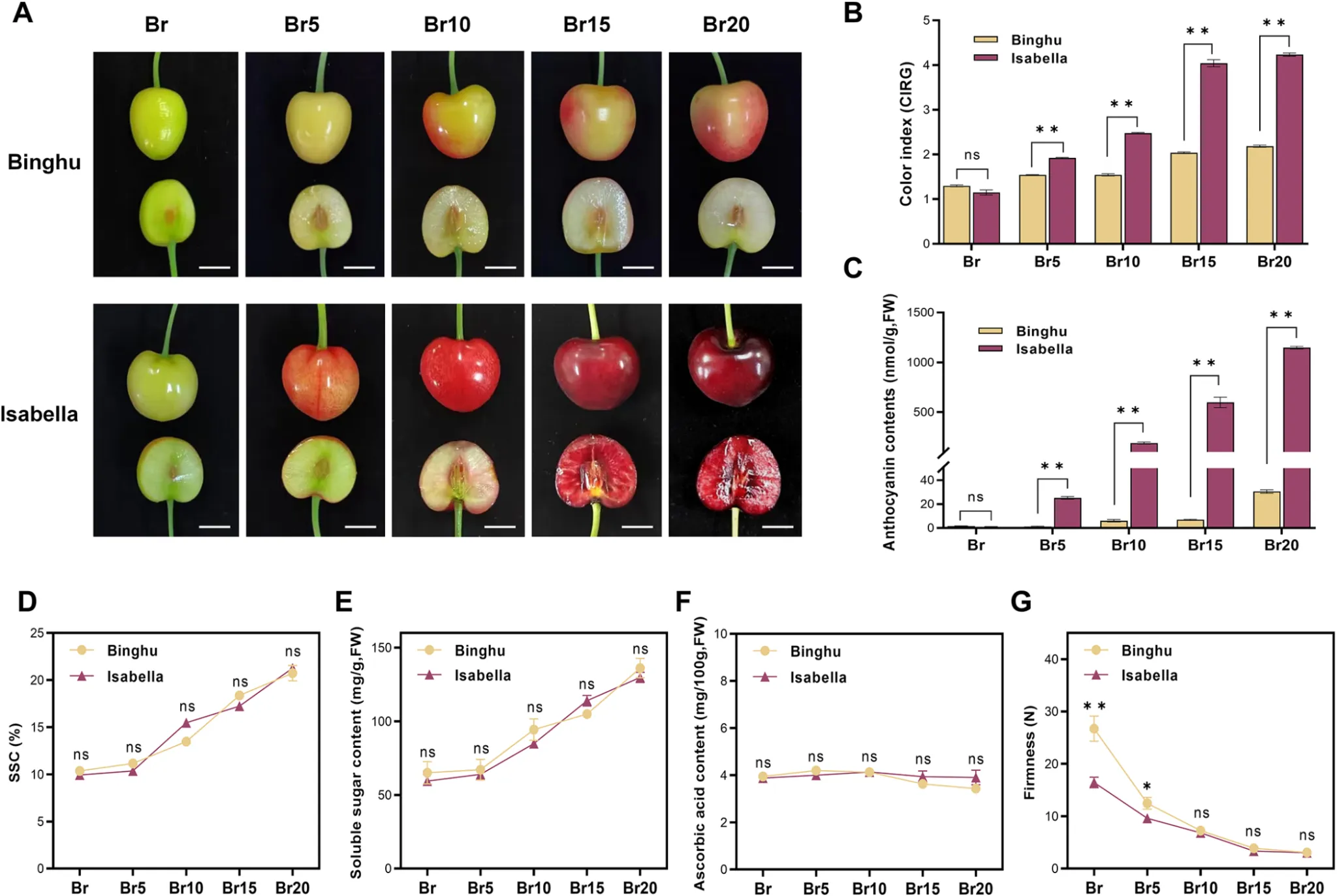

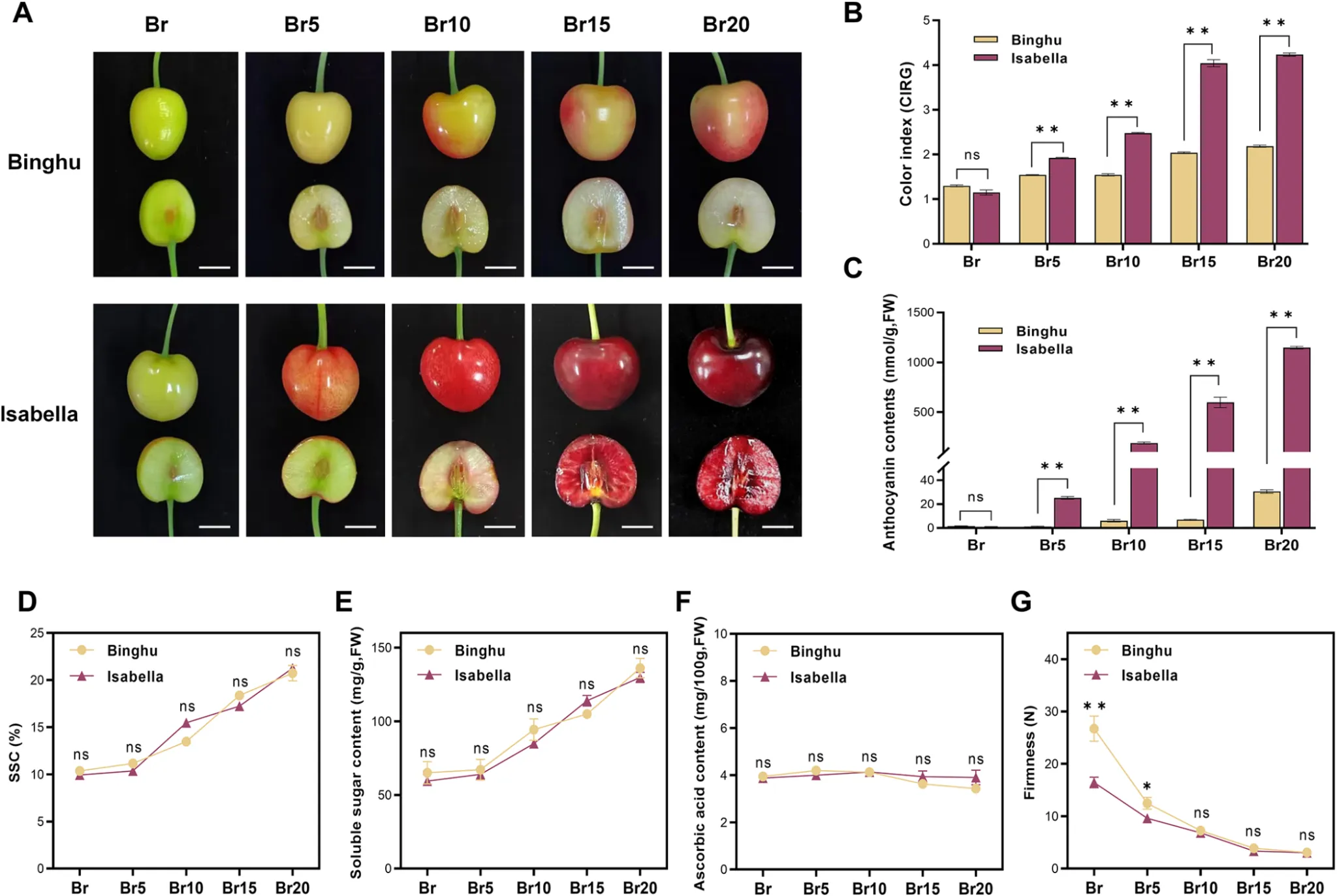

In this study, researchers compared two cherry varieties with contrasting coloration—one yellow and one dark red—to identify the factors influencing fruit color at harvest.

The sweet cherry cultivars examined were ‘Binghu’ and ‘Isabella’, collected from 9-year-old trees grown in an experimental orchard located in Wenchuan, Sichuan Province (China).

By combining chemical analyses with transcriptomic studies, the researchers found that fruit color is determined not only by the total amount of anthocyanins but also by the quantity and relative proportions of individual pigments.

The role of cyanidin-3-glucoside

One of these, cyanidin-3-glucoside (Cy3G), proved to be especially crucial in generating the dark red coloration of the fruit.

The genetic investigation then revealed a cluster of genes involved in anthocyanin production, among which PavMYB.C2 stood out.

This transcription factor functions as a key regulator of pigment biosynthesis. In fact, it acts like a genetic “switch” that turns on anthocyanin production during ripening.

PavMYB.C2 as a genetic switch

Its importance was experimentally validated: when PavMYB.C2 was overexpressed in cherries, the fruits accumulated more pigments, particularly cyanidin-3-glucoside; conversely, reducing its activity led to a marked decrease in coloration.

This demonstrates that PavMYB.C2 is essential for the development of the deepest red tones.

A further step in the study was to identify how this gene exerts its effect.

The researchers discovered that PavMYB.C2 directly activates UFGT, a gene responsible for the final step in the biosynthesis of cyanidin-3-glucoside.

Differential accumulation of anthocyanins between two cultivars with distinct fruit coloration.

Differential accumulation of anthocyanins between two cultivars with distinct fruit coloration.

(A) Phenotypes comparison of ‘Binghu’ and ‘Isabella’ sweet cherry fruits at different ripening stages. ‘Binghu’ and ‘Isabella’ are two commonly cultivated sweet cherry cultivars. Ripening stages include the breaker stage (Br) and 5-20 days post-breaker stage (Br5-20). Scale bar = 1 cm. (B) Color index of red grape (CIRG) values for the fruits at each ripening stage. (C) Anthocyanin content in the fruits at each ripening stage. (D-G) Analysis of fruit ripening-related phenotypes. (D) Soluble solid content (SSC), (E) Soluble sugar content, (F) Ascorbic acid content, and (G) Fruit firmness at each ripening stage. Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 5). Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-tests; asterisks denote significant differences compared to ‘Binghu’ at p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**); ‘ns’ indicates no significant difference compared to the control.

Mechanism of gene activation

This activation depends on a specific serine residue (S68) within the MYB domain of the protein, which is necessary for the transcription factor to bind DNA and stimulate UFGT expression.

Once UFGT is activated, Cy3G synthesis increases and the fruit becomes darker.

Overall, the study shows that fruit coloration results not only from the total anthocyanin content but also from the precise composition of different pigment molecules, all controlled by a complex genetic network.

Agricultural implications

The PavMYB.C2–UFGT regulatory module thus emerges as a fundamental determinant of final cherry coloration.

These findings may have important implications for agriculture: understanding the genetic mechanisms underlying pigment formation could support the development or selection of fruit varieties with more appealing colors and improved nutritional value.

Source: Pei Y, Tang W, Huang Y, Li H, Liu X, Chen H, et al. (2025) The PavMYB.C2-UFGT module contributes to fruit coloration via modulating anthocyanin biosynthesis in sweet cherry. PLoS Genet 21(6): e1011761. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1011761

Source images: Yangang Pei et al., 2025

Melissa Venturi

University of Bologna (IT)

Cherry Times - All rights reserved