At first glance, Washington's cherry season last year might seem like a success. Growers harvested over 63,000 tons more than the previous year, and the cherries were of high quality too.

But timing is everything.

The cold delayed the harvest of California cherries, overlapping their season with Washington's. The market was flooded. Additionally, a mid-May heatwave (which rapidly melted the mountain snowpack) triggered an early and massive ripening in Washington's orchards.

Millions of pounds of sweet cherries hit grocery store shelves over weeks instead of months. Prices plummeted, and Washington's cherry industry, the largest in the country, suffered an estimated $100 million loss.

For generations, Washington farmers have made their living in an unpredictable business. But now they are grappling with a series of natural disasters, exacerbated by climate change, with more looming on the horizon. As the number of growers declines, the industry also faces consolidation of food chains.

Costs are rising and prices are falling, even as companies continue to profit, said Matthew Whiting, a professor of tree fruit horticulture at Washington State University. "It's not sustainable," Whiting said.

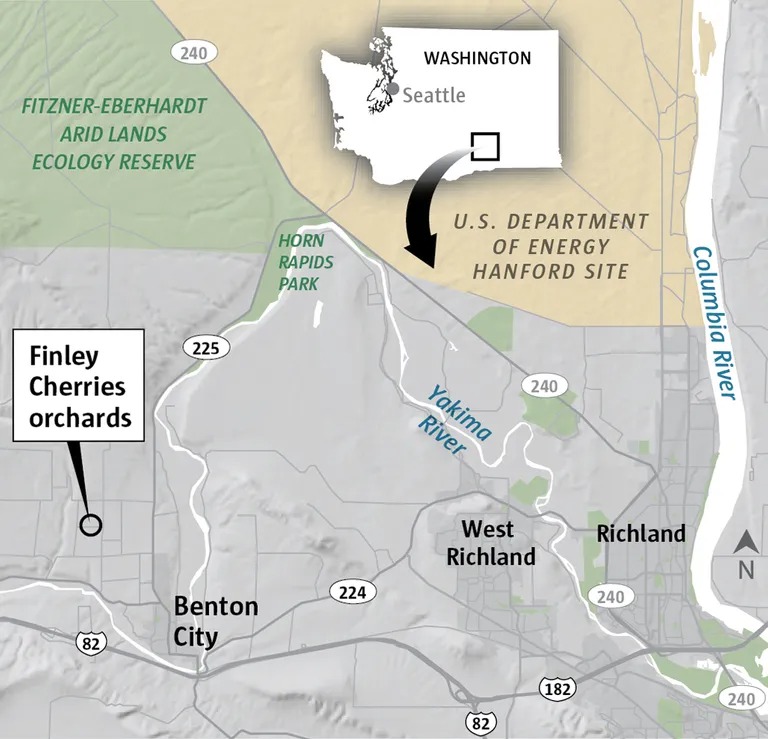

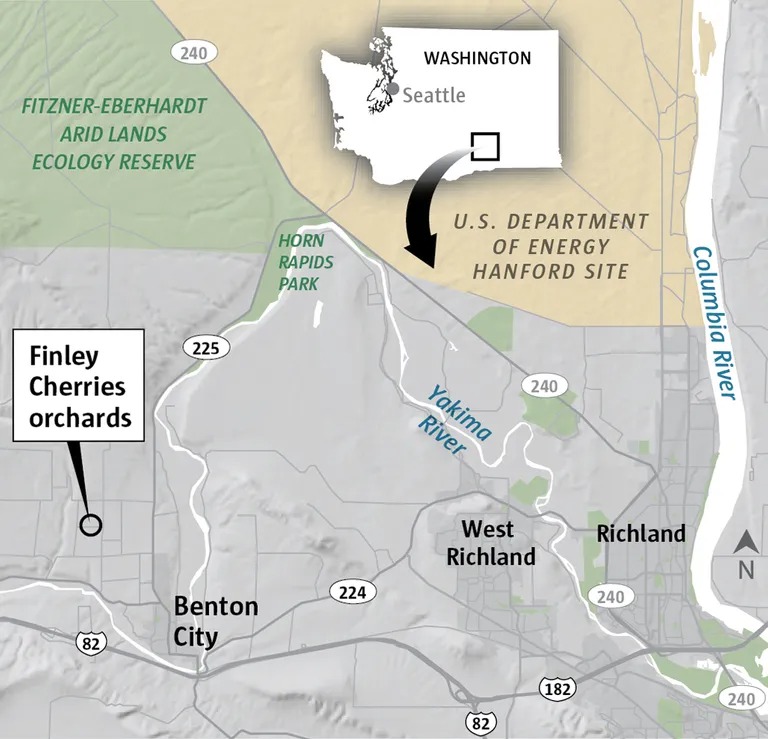

Every season, growers calculate how much they need to earn to survive, said John Pringle, co-owner and director of Finley Cherries in Benton City. Increasingly, only the larger companies can survive. Pringle stood in a gravel field, surrounded by plastic bins of cherries stacked five levels high. With a quick motion, he grabbed a single cherry from a nearby crate, popped it into his mouth, and tossed the pit over his shoulder.

"The 40-acre guy can't make it anymore," he said.

Natural Disasters

Since the pandemic - when growers faced border closures, lockdowns, and transportation shortages - Washington's cherry industry hasn't had a moment of respite.

Cherries are a particularly delicate crop, not storable like apples or onions. They must be handpicked within a certain timeframe, and once off the tree, the clock starts ticking. This makes them especially vulnerable to climate fluctuations, and climate change is pushing extremes in both directions.

Growers quickly recall the deadly record-setting heat dome of 2021, which settled over the region for a week. The heat was so intense that cherries literally melted off the trees. Those that survived suffered sunburn and other quality issues. A fifth of the crop was lost.

The following year went in the opposite direction.

Shawn Gay, Pringle's partner and co-owner of Finley Cherries, recalls walking through the orchards in April 2022, watching snow pile up on top of beehives and cherry trees. He had never seen such a late snowfall. The Northwest cherry harvest fell to its lowest point in over a decade.

Last year, the cherry harvest rebounded almost too much. The overlapping seasons and mass ripening caused the market to collapse for growers. Farmers can prepare for intense heat and colder weather, Gay said. They can cover crops or move fans into the orchards. These are tried-and-true methods that work to some extent.

But how can they defend against a flooded market and a dramatically short season? Gay looked down the row of his orchard from behind his sunglasses, as crews moved from tree to tree. The dull thud of cherries dropping into plastic buckets filled the air. "It's a hard thing," Gay said.

This year should be better, Gay said. The state is in a drought emergency and the polar vortex in January damaged (or devastated) some orchards further north, so yields will be lower. But the cherries on his trees are of the highest quality he has ever seen.

In this industry, no two years are alike, agree the partners at Finley Cherries. But for Gay, and others like him, a couple of questions always remain. Will this year be profitable enough to continue? And how many more bad years can the company endure?

Money Loss, Farmer Loss

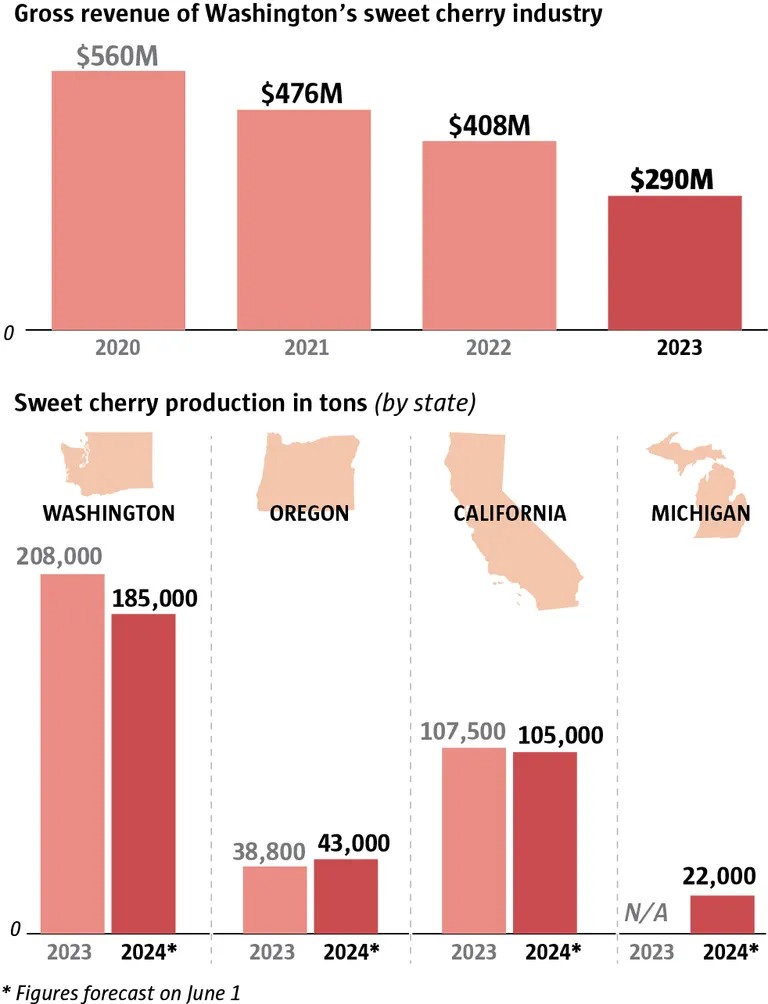

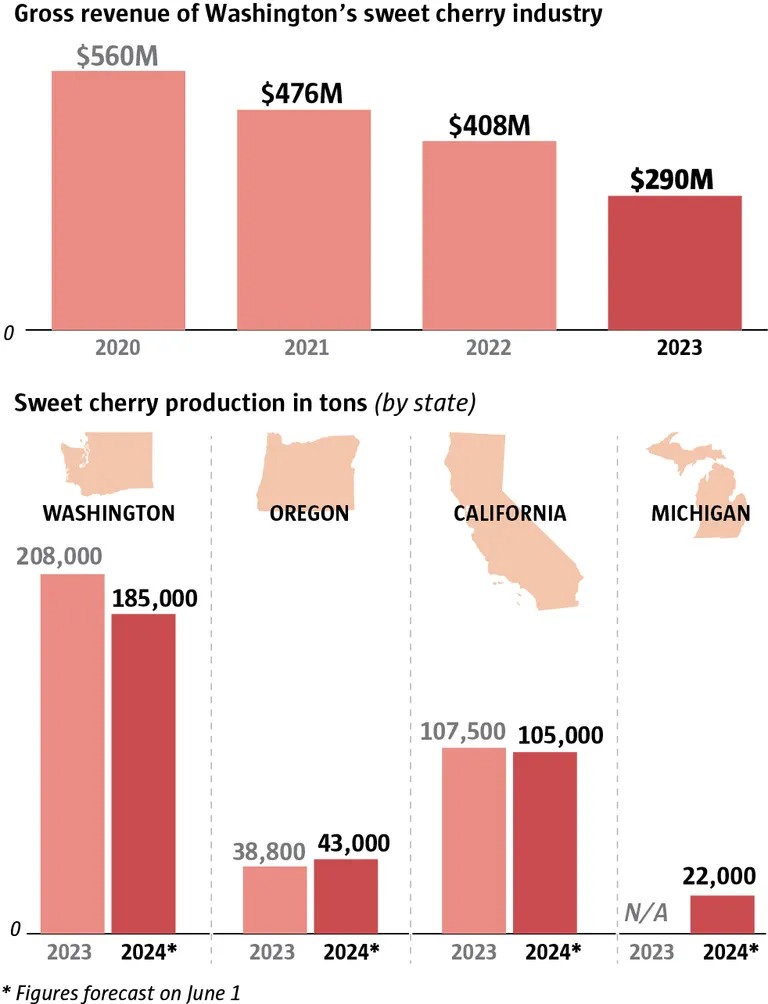

Not only have Washington's cherry growers earned less in the past four years, but the sector has been losing farmers for even longer.

Washington's sweet cherry growers earned about $560 million in 2020, according to data collected by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The figure dropped to $476 million in 2021, to $408 million in 2022, and to $290 million last year, with a nearly 50% decline over four years.

And costs are rising, said Jon DeVaney, president of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association. Like everyone else, farmers are feeling high inflation, but they also face high overhead and transportation costs. Additionally, adapting to climate change (low-water-use technologies, shade cloths, automatic sprinklers, and more) is expensive.

Labor costs are also rising, said Mark Hambelton, owner and manager of Double M Orchards in Quincy, Grant County. According to Hambelton, some farmers stick their heads in the sand and try to ignore the changing dynamics. But they can't hold out for long.

The rising costs and thinning margins mean that growers end up leaving the business, often selling their land to larger companies. At its peak in 2002, Washington had 2,432 sweet cherry growers. Since then, the number of industry participants has dropped by over 40%, to 1,448 in 2022, according to the USDA.

As the sector contracts, supporting businesses also suffer, from tractor supply stores to restaurants. Even though larger companies continue to farm the land (the total sweet cherry acreage has increased over the past decades), they may have a lesser connection to the region and the crops they grow, DeVaney said.

Some survive through diversification, says Gay. If the cherry season falters, they can fall back on apples, wine grapes, or peaches.

Federal relief loans are also available, after the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture declared last season a disaster. But Jon Wyss, Washington state director for the USDA's Farm Service Agency, said historically few growers take advantage of this program.

Hambelton has not applied for a relief loan, but he feels better knowing the money is available. If the crops don't improve soon, maybe more growers will participate, he said. However, growers are just one part of the equation.

A Broken System

The demand for food obviously isn't going away, Pringle said with a wry smile. People need to eat every day. And farmers need to figure out how to stay in business.

But they are in a tough position. Since cherries are a highly perishable product, Gay said growers are forced to "price make." This means they have to accept whatever price the market offers because they don't have the time to wait for a better offer.

With the disappearance of local wholesalers and grocery stores, replaced by a monoculture of corporate chains, growers have even less power when selling.

Pringle pointed out the controversial proposed merger between Kroger (QFC and Fred Meyer) and Albertsons (Safeway), which would further consolidate the retail market. If the merger goes through, Kroger-Albertsons and Walmart together would control 70% of the market nationwide, Vox reported.

Sweet cherry growers are earning less for their crops, customers are paying more for groceries (12% more in Seattle, according to 2022 data), and the companies behind the stores are reporting huge profits.

Perhaps growers could band together to form some sort of regional market and prevent their prices from falling too low, said Whiting, a tree fruit horticulturist at WSU. Or they could take a cue from apple growers and regulate the acreage on which different types of cherries can be grown and in what quantities.

Cherry growers are the only ones along the supply chain who do not have a guaranteed profit, he said. "The whole system is so broken," he said.

According to Whiting, last year the farmers did everything right, given the information they had. If the same conditions arise, they can explore relatively untapped cherry markets, like those in the southeastern United States, to try to sell some of the excess product.

But in the big picture, fundamental changes are needed to keep Washington's cherry industry vital. "It's a depressing lesson," Whiting said. "It's not as simple as just doing the best job possible."

Source: The Seattle Times

Image: The Seattle Times

Cherry Times - All rights reserved