Studying supercooling in cherry trees

Scientists at the University of British Columbia Okanagan are studying how sweet cherry trees protect their flower buds from winter frost, using a natural mechanism called supercooling.

Dr. Elizabeth Houghton, a graduate of the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Science, published a study in the journal Plant Biology analyzing this phenomenon. Supercooling allows the liquids within plant cells to remain in a liquid state even at subzero temperatures, preventing ice formation. However, this delicate balance can break if impurities or ice crystals intervene, leading to sudden freezing.

This process is vital for flower buds, which must survive the cold months to ensure the production of fruits in the following season.

The impact of extreme cold

The importance of better understanding this mechanism became clear after an exceptional cold wave hit Okanagan in January 2024, with temperatures dropping as low as -27°C (-16.6°F). The damage to fruit trees was devastating, with estimates indicating a loss of 90% of the anticipated summer crop.

Many tree species have strategies to withstand cold, but supercooling in stone fruits, like cherries, remains poorly understood.

A research focus on cherry trees

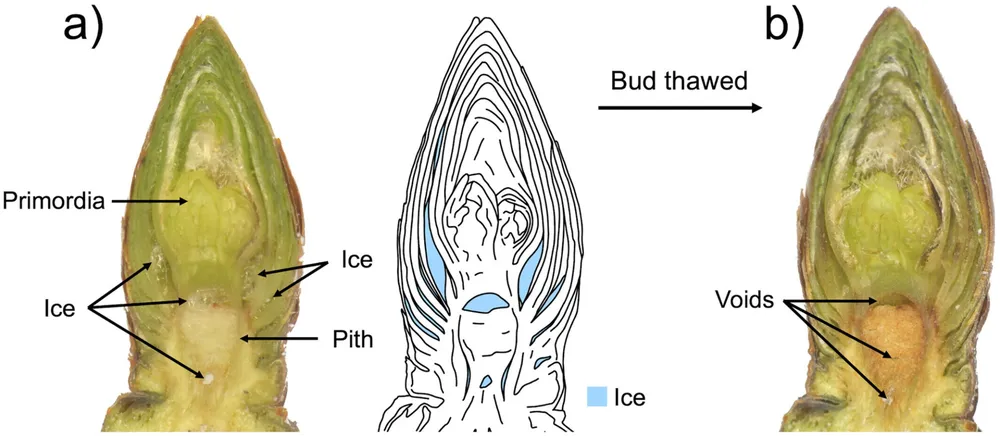

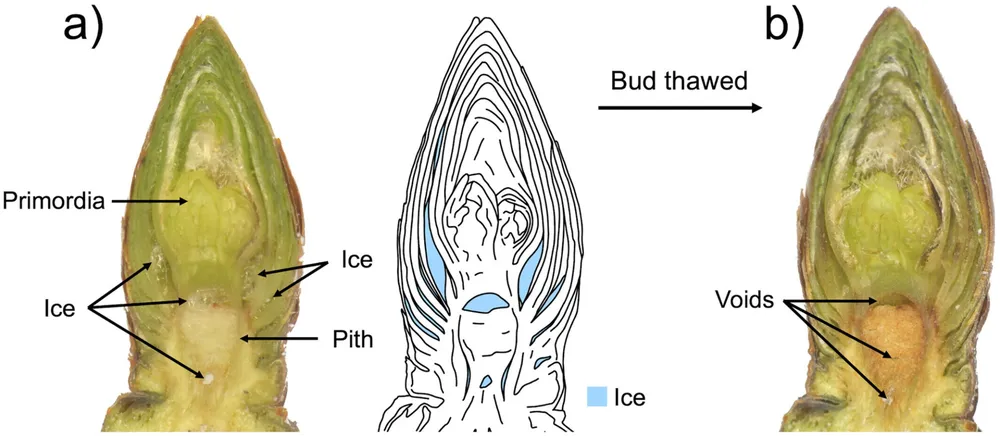

Figure 1: Ice accommodation in overwintering sweet cherry flower buds exposed to in-field sub-zero temperatures. Photographs taken under a dissecting microscope on 24 February 2023 of a sweet cherry flower bud that was: (a) held at in-field freezing temperatures after experiencing a natural cold snap along with a digital diagram of the same flower bud to highlight regions of ice accommodation, then (b) thawed to room temperature. Credit: Plant Biology (2024). DOI: 10.1111/plb.13697

Figure 1: Ice accommodation in overwintering sweet cherry flower buds exposed to in-field sub-zero temperatures. Photographs taken under a dissecting microscope on 24 February 2023 of a sweet cherry flower bud that was: (a) held at in-field freezing temperatures after experiencing a natural cold snap along with a digital diagram of the same flower bud to highlight regions of ice accommodation, then (b) thawed to room temperature. Credit: Plant Biology (2024). DOI: 10.1111/plb.13697

“The ability of sweet cherry trees to withstand winter frost through supercooling is fascinating. In this state, cellular liquids do not freeze despite subzero temperatures,” explains Dr. Houghton. “But we still don’t know exactly how this happens in certain plant structures. We want to dive deeper to understand how flower buds survive such extreme conditions.”

Unlike previous research, which mainly focused on peaches, this study shifts attention to cherries. Their buds contain more primordia — cellular structures that will develop into flowers and later into fruits — compared to peach buds, which contain only one.

The critical moment: from snow to spring

Dr. Houghton examined various aspects of the phenomenon: from ice formation inside the buds to the freezing of outer layers, and the changes occurring within the buds as temperatures begin to rise with the arrival of spring.

One of the most critical aspects is the transition from winter to spring. As the buds grow, they gradually lose the ability to stay supercooled, becoming vulnerable to sudden cold snaps.

“Cherry buds have an extraordinary ability to protect themselves from frost in winter, but this defense weakens with spring growth,” the researcher explains. “We want to better understand how these buds endure such harsh winter temperatures. And with the uncertainty surrounding climate change and the possibility of more frequent and intense cold waves, it’s crucial to learn from these plants to develop strategies that safeguard future crops.”

Source: Phys.org

Cherry Times - All rights reserved