Resilience key factor for cherry rootstocks

01 May 2023

A thoughtful choice of rootstock allows cherry trees to grow moderately, with a good dwarfing effect, produce well and adapt to critical conditions without compromising cherry quality.

In holometabolous insects, the selection of an oviposition site by the adult must align with the developmental needs of the larvae.

In the case of Drosophila suzukii, females possess an enlarged, serrated ovipositor—an evolutionary adaptation that allows them to lay eggs inside ripening fruits, a substrate typically inaccessible to other Drosophila species.

This ability has enabled D. suzukii to colonize a wide range of fruit types during their ripening stage.

Thanks to this physical adaptation, D. suzukii females can lay eggs in fallen, damaged, or decaying fruits.

However, they show a strong preference for intact fruits.

This choice, though, presents a nutritional challenge for the larvae.

Unlike D. melanogaster, which develops in decaying fruit rich in yeasts and other proteinaceous microorganisms, D. suzukii larvae are deposited into a closed environment with firm flesh, high in sugars but low in proteins.

Interestingly, while adult flies prefer carbohydrate-rich substrates for egg-laying, larvae grow faster on protein-rich or more nutritionally balanced substrates.

The mismatch between adult preference and larval nutritional needs might seem disadvantageous, yet D. suzukii larvae successfully complete their development in ripening fruit.

To understand how this is possible, researchers from the Max Planck Institute and the Leibniz Institute (Jena, Germany) studied the development of D. suzukii larvae in blueberries.

They found that first-instar larvae actively modify their environment to make it more suitable for development.

Given that the main drawbacks of ripening fruit are its firm texture and low protein content, the study explored the larvae’s survival strategy in detail.

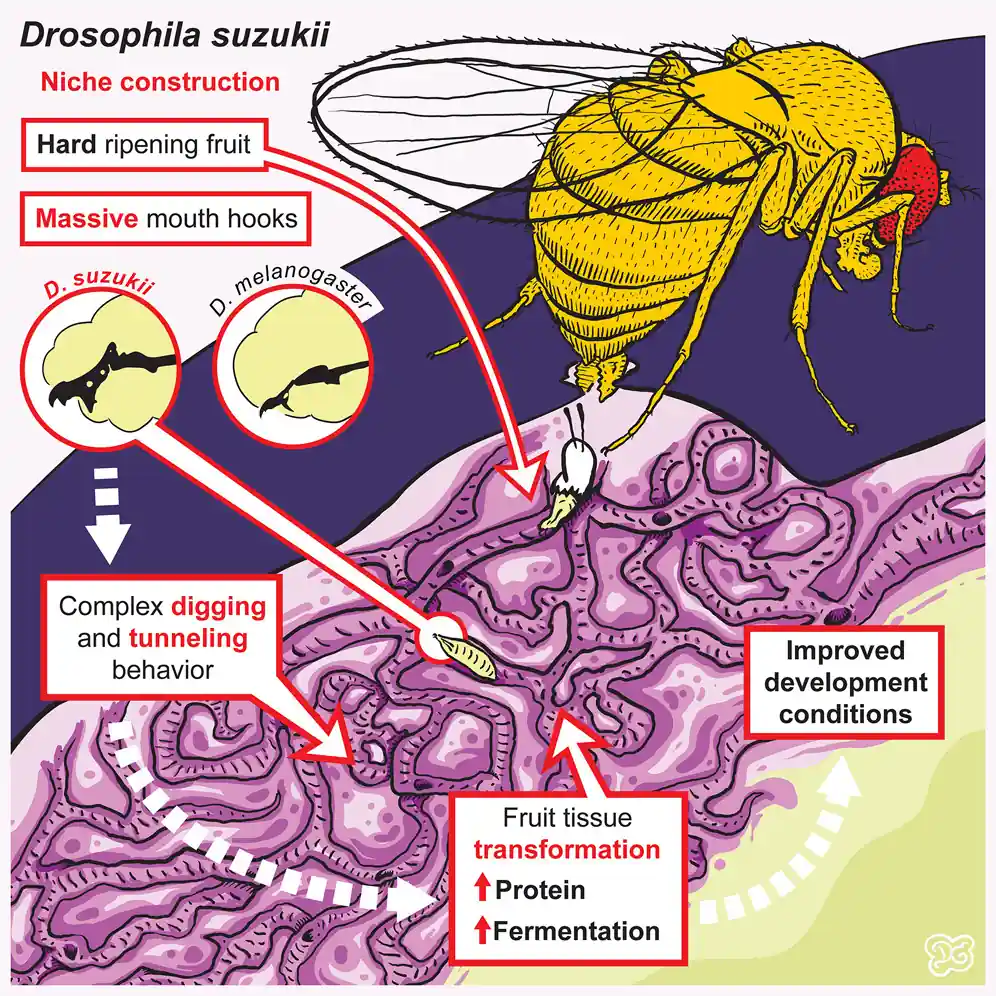

Figure 1: Developmental pattern of Drosophila suzukii

Figure 1: Developmental pattern of Drosophila suzukii

First, their powerful mouthparts allow them to tunnel through the fruit flesh.

As they dig, they soften the flesh, creating an increasingly complex network of tunnels.

This behavior not only improves physical access to the substrate but also transforms the fruit into a more nutritious resource.

Additionally, the larvae benefit from the presence of an active microbial community within the fruit.

The tunnels may facilitate the entry and spread of microbes introduced by the female during oviposition.

It was observed that larvae often create tunnels that loop back to their origin—likely the egg-laying site and source of microbial inoculum.

During tunneling, larvae ingest fruit pulp and defecate within the tunnels, further promoting the spread of microbes throughout the fruit.

The presence of fermentation-related compounds such as acetic acid, acetoin, and isoamyl alcohol in infested fruit is clear evidence of microbial activity, which provides a protein source for the larvae.

While some microbes—such as acetic acid bacteria—can be harmful under certain conditions, the data show that fermentation byproducts, including acetic acid, are attractive to larvae and may guide them toward areas of intense microbial activity during tunneling.

Overall, the study suggests that D. suzukii larvae do not merely tolerate the maternal oviposition substrate—they actively transform it.

Through digging and feeding behaviors, they alter the physical and nutritional characteristics of the fruit, turning an otherwise unsuitable environment into a viable habitat.

This behavior is a clear example of niche construction, in which an organism modifies its surroundings to meet its ecological and physiological needs.

Source: Shaping the environment – Drosophila suzukii larvae construct their own niche, Diego Galagovsky,Ana Depetris-Chauvin,Grit Kunert,Markus Knaden,Bill S. Hansson, iScience. Elsevier, 20 December 2024 https://www.cell.com/iscience/fulltext/S2589-0042(24)02566-5

Image source: Galagovsky et al. 2024; WSU Fruit Tree

Melissa Venturi

University of Bologna (ITA)

01 May 2023

A thoughtful choice of rootstock allows cherry trees to grow moderately, with a good dwarfing effect, produce well and adapt to critical conditions without compromising cherry quality.

22 Nov 2024

Complementary to the application of cytokinin to enhance stage I of fruit growth and improve caliber, the other important stage when defining fruit caliber corresponds to stage III of fruit growth and development where the hormone responsible for this process is Gibberellic acid.

04 Mar 2026

In cherry orchards of the Maule Region (Chile), circular paper chromatography is evaluated as a qualitative method to understand soil properties. Results highlight links with organic matter and agronomic management, supporting more sustainable production strategies.

04 Mar 2026

Chilean cherry exports to China are projected to rise by 14.3% by 2030, increasing market pressure and pushing prices down. Industry leaders and the SNA warn that up to 30,000 hectares may need to be removed to restore balance and protect long-term profitability.