Climate conditions in Chile are becoming increasingly adverse for cherry production. As a result, new methods are already being explored to address this difficulty: one option might be to conduct harvesting during periods when this work is not usually performed.

Climate change is a reality that must be addressed. In recent years, central Chile has been hit by several natural disasters, such as floods or river overflows, which have had direct repercussions on agricultural production, causing severe damage to cherry orchards.

However, it is not only these types of events that affect cherry production, as the greenhouse effect and the El Niño phenomenon are major causes of high temperatures and low relative humidity in our region, which in turn cause severe damage to crops.

Hail, intense cold fronts, heatwaves, low relative humidity, storms... around the world, there are meteorological phenomena that threaten cherry production. Technologies have been developed to mitigate damage for each of these phenomena: frost towers, rain covers, hail nets, sprinklers, windbreaks, and humidification, among others.

However, climatic events are intensifying year by year, so that in some cases these solutions are no longer sufficient. When focusing on cherry post-harvest, there are environmental phenomena directly related to fruit damage observed upon arrival at their destination.

High temperatures and low relative humidity at harvest time significantly reduce the shelf life of cherries, affecting not only the entire production but also their selling price.

Night Harvesting in the USA

A few weeks ago, Sebastian Johnson visited the states of Washington and Oregon on the west coast of the United States, in the midst of the cherry harvest season with an intense summer, with daily temperatures exceeding 42°C and relative humidity below 15%, a phenomenon not much different from our country, where temperatures at harvest time can exceed 30°C or 32°C and humidity around 15%.

These conditions trigger one of the two main problems of cherry post-harvest according to his criteria: metabolism and dehydration.

Part of the visit was primarily aimed at observing harvesting and some processing plants, where it was possible to see how night harvesting was carried out in some fields, focusing on two aspects: that workers were not exposed to high temperatures and that cherry deterioration was avoided.

In conversations with some field managers who worked at night, they cited the quality of work for harvesters as the only reason for night harvesting, rather than the desire to improve the cherry harvesting environment.

It was not clear that night harvesting would have a huge benefit on the conditions of cherries upon arrival. In many of the fields visited in Washington, we were told that harvesting was stopped before the ambient temperature reached 90°F (32°C) to protect the pickers.

As a result, night harvesting started at 2:00 AM and ended at 10:00 AM. This way, workers were rested and could harvest for the necessary hours. At the same time, many did not realize they were creating an excellent harvesting environment, slowing down cherry metabolism, reaching pulp temperatures between 20°C and 25°C, and reducing dehydration by over 50%.

In Chile, night harvesting can be observed with table grapes, which from a metabolic and dehydration perspective is significantly better, making a big difference in the fruit depending on the time of harvest and its shelf life during the days following this process.

However, before considering implementing night cherry harvesting in our country, we need to address and evaluate several important points regarding field logistics, safety measures, harvester training, orchard lighting, the presence of adequate workers and supervisors, among other aspects.

Often, work begins with the intention of starting as early as possible, but there are delays of all kinds, such as waiting for the tractor driver, delivery of ladders and bins, arrival of contractors, etc., and the day starts only at 07:00 or later, with a temperature already very close to 20°C. The situation is different in other fields where conditions are already set for the start of the first harvest of the day at 06:30, a situation that should be emulated before considering night harvesting.

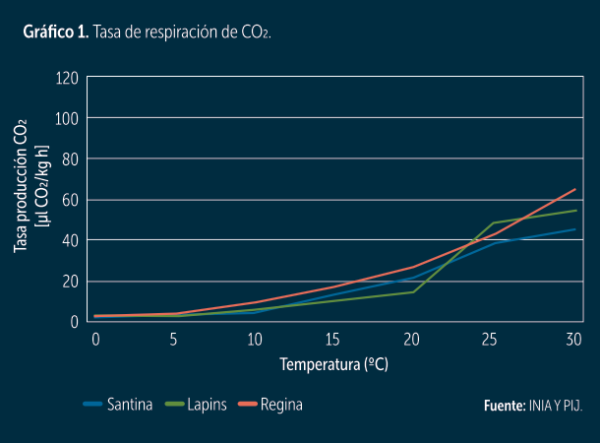

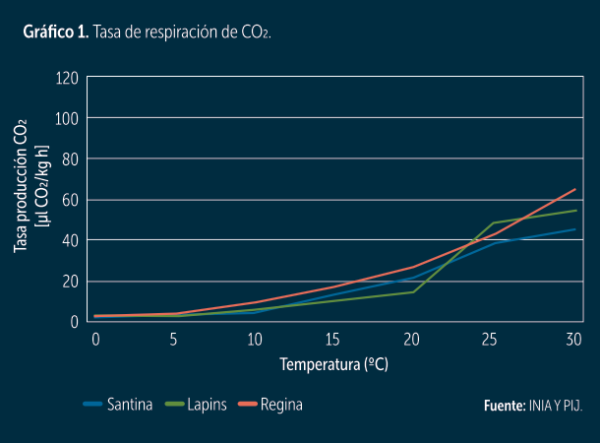

Image 1: CO2 respiration rate in Santina, Lapins, and Regina cultivars.

Image 1: CO2 respiration rate in Santina, Lapins, and Regina cultivars.

In many areas, and depending on various factors such as the conduction system, planting density (high or low), and tree age (more or less bushy), harvesting could start without major inconveniences at 06:00 AM, leaving everything ready the day before, or the entry time could start earlier so that the first cherry is picked at that hour, whether in groups of 40 or 250 people.

At 5:00 AM in Washington, the sky was neither dark nor clear, so with a simple search, we learned that this phenomenon is called twilight, and in Chile, we could start from there. It does not seem unreasonable to organize harvesting at 5 AM, thinking that an hour later there is adequate natural light.

The Main Enemies of the Cherry

The main enemy of the cherry is time. Time deteriorates everything. All damage is measured per unit of time, such as dehydration measured in %/hour. If we halved processing times, we could say we would have half the condition problems at destination. There are also two other harmful aspects of cherry condition at destination: metabolism and dehydration.

Metabolism is, in simple terms, the chemical process through which the cherry obtains the energy necessary to continue living through respiration.

When the cherry breathes, oxygen oxidizes the reserves (organic acids and sugars), generating water, CO2, and energy. Not all this energy is used; excess energy is dissipated as heat, raising the pulp temperature and further increasing metabolism.

Excess energy is dissipated as heat, increasing the pulp temperature and causing further metabolism increase. Therefore, we need to work on strategies that help us avoid increasing pulp temperature in the field and rapidly lower it when it arrives at the processing plant.

Together with INIA, we analyzed the respiration rate of cherries over two seasons as a function of pulp temperature (see graph 1). The analysis shows that the higher the pulp temperature, the higher the respiration, but from 20°C to 30°C, metabolism increases threefold, so our goal is to avoid the pulp exceeding 20°C.

Among the damages caused by metabolism in cherries are increased reserve consumption, accelerated senescence processes, reduced firmness, higher susceptibility to microorganism attacks, reduced organoleptic characteristics, variations in the SS/TA ratio, and increased production of ethylene, a hormone that triggers the senescence process.

Dehydration and VPD

Another aspect concerning cherries is dehydration, or the loss of water through structures that allow for gas exchange. The fruit does not necessarily dehydrate simply because it has these structures. Certain environmental conditions must be present for this physical process, which is directly related to the ambient pressure, also known as vapor pressure.

Vapor pressure is measured with temperature and humidity (VPD). If the VPD of the cherry is the same as that in the field during harvest, we can assume there is no dehydration. Conversely, if the fruit's VPD is higher than that during storage, dehydration is occurring, and measures must be taken to prevent it.

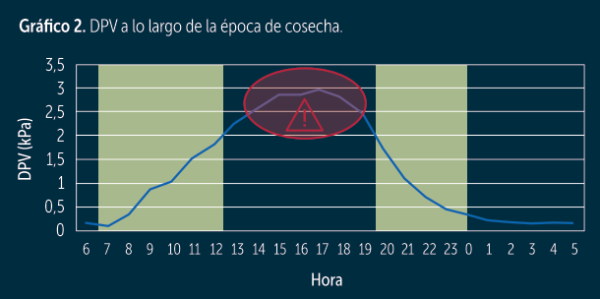

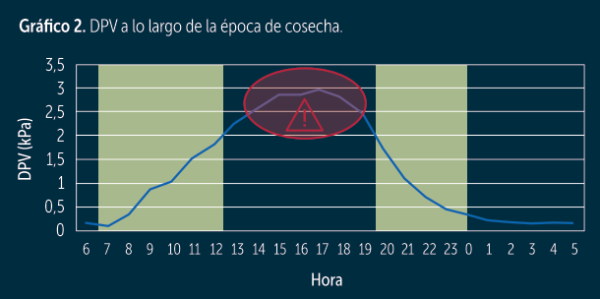

Image 2: Vapor pressure deficit during the harvest period.

Image 2: Vapor pressure deficit during the harvest period.

The index showing the level of dehydration is called vapor pressure deficit (VPD), which is a simple subtraction between the vapor pressure of the cherry and one of its environments, in this case, the storage. The closer this index is to 0, the less the dehydration. In other words, if we get values between 0 and 0.5 kPa of vapor pressure deficit, we can state that dehydration would not be a serious problem.

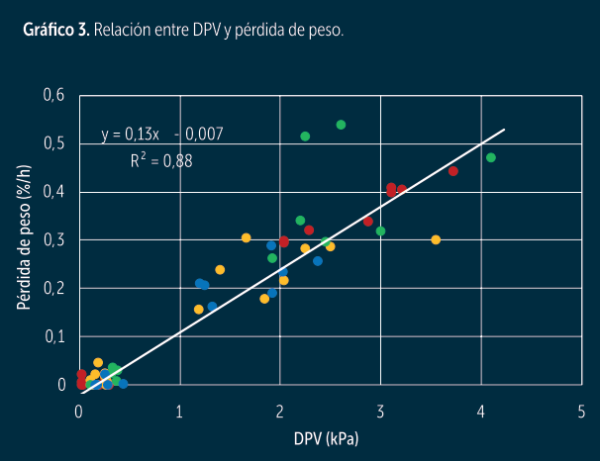

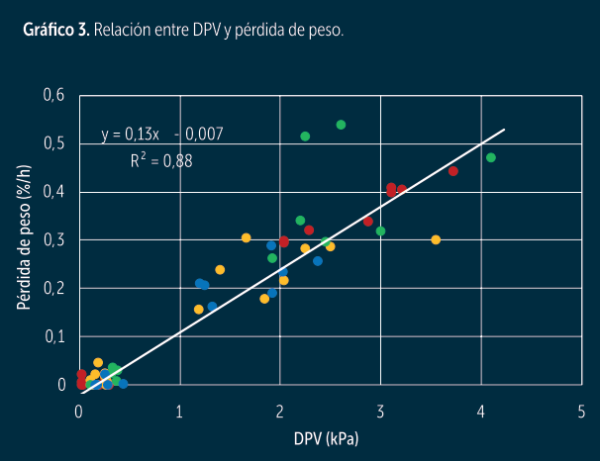

VPD does not tell us how much we are dehydrating but rather in which situations one scenario dehydrates more than another. However, if we look at graph number 3, which relates vapor pressure deficit to weight loss, we can infer weight loss at a certain vapor pressure deficit.

Graph 2, created during previous harvest seasons, shows that the closer the environmental VPD value is to 0, the less the dehydration and the fruit's metabolism, so the best time for these conditions is from 10:00 PM to 10:00 AM, which aligns with our proposal that the best time for harvest is at dawn or during the night.

Relationship Between Vapor Pressure Deficit (VPD) and Weight Loss

One of the main goals to avoid cherry dehydration is to make the VPD of the environment as similar as possible to that of the fruit, which can be artificially achieved with humidification systems in storage centers in the field, as these modify the temperature and relative humidity (RH) of the environment, altering the storage VPD and preventing an increase in pulp temperature, which in turn prevents a reduction in cherry weight when it reaches its final destination.

Understanding the importance of the relationship between VPD and weight loss is fundamental to grasping the consequences of not implementing adequate measures to prevent this phenomenon in post-harvest.

Image 3: Relationship between vapor pressure deficit (VPD) and weight loss.

Image 3: Relationship between vapor pressure deficit (VPD) and weight loss.

The fruit aspects most affected by extreme post-harvest conditions are stem browning and fruit firmness, important attributes that impact the price of cherries when they reach the Chinese market.

Strengthening Simple Steps

To improve all the post-harvest problems and/or damages described above, related to dehydration and metabolism, we propose some ideas already tested and used in the cherry industry, such as early harvest, being strict about starting at 6:00 AM, and trying to incorporate morning harvesting at 5:00 AM.

Interrupt the harvest with pulp temperatures not exceeding 20° or 25°C, use mesh coverings on each harvest bin to lower the ambient temperature by 10°C, use wet sponges, wet the fruits to form a water film on the surface of the skin, which protects them from dehydration, use humidified storage, and transport to processing facilities in refrigerated trucks.

We should also incorporate humidification systems at the receiving points of processing plants to prevent cherries from being damaged by the environment while waiting for the hydrocooler process.

In raw material chambers, the residual water from the hydro protects cherries from dehydration during the first two days, so it is good to humidify raw material chambers when we know the fruit will remain there for more than two days. Finally, as mentioned earlier, time is our main enemy, so we need to define the timing for each production process, monitor it, and adhere to it.

Each year, environmental conditions become more extreme (large heat waves in summer and significant lack of cold in winter), so we need to adapt to the new conditions of global warming, and if this means moving towards morning or even night harvesting, it will soon need to be a reality.

Source: Redagrícola

Images: Redagrícola

Cherry Times - All rights reserved