Sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) combines a high economic value with extremely demanding market conditions. With an annual production of around 2.7 million tonnes and prices that can reach USD 13,000 (approximately EUR 11,900) per tonne, the sector justifies investments in quality, post-harvest management and logistics.

However, this same system generates a considerable volume of agro-industrial waste – pomace (skins and press cake), stems and pits – which can account for up to 30% of total production (Farias et al., 2025). Traditionally, these fractions have been treated as waste: they are costly to manage, require space, may cause environmental problems and, above all, represent a loss of biomass with high chemical potential.

Circular economy and new approaches

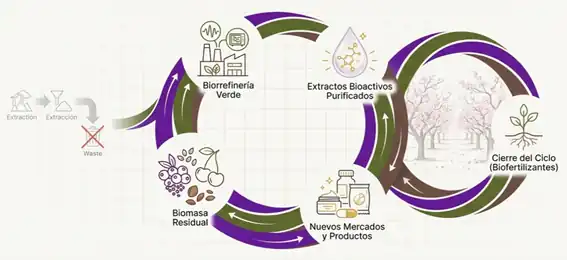

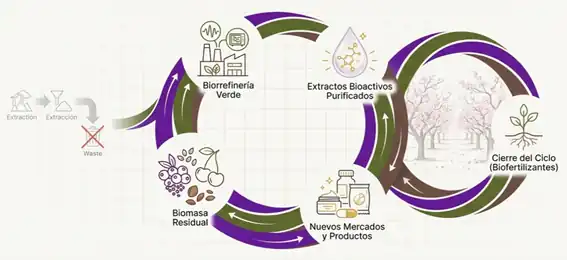

The circular economy proposes a paradigm shift: considering these waste streams as secondary raw materials. In the cherry sector, this translates into a move toward biorefinery systems capable of recovering bioactive compounds, designing functional ingredients and, where appropriate, generating materials or agro-environmental solutions.

This is not about “finding a way out” for waste, but about building additional value chains that coexist with the fresh fruit market and mitigate the inevitable losses associated with commercial grading and processing. The expected outcome is twofold: reduced environmental impact (less final waste) and increased economic efficiency (greater value per tonne produced).

Figure 1. “From fruit to value streams”. Conceptual representation of the process from fresh cherries to green biorefinery, recovery of bioactive extracts, creation of new products and partial closure of the cycle through agro-environmental uses. Credits: author’s work (synthesis). Source: review by Farias et al. (2025) and studies cited therein. No graphical material from the original article is reproduced.

Figure 1. “From fruit to value streams”. Conceptual representation of the process from fresh cherries to green biorefinery, recovery of bioactive extracts, creation of new products and partial closure of the cycle through agro-environmental uses. Credits: author’s work (synthesis). Source: review by Farias et al. (2025) and studies cited therein. No graphical material from the original article is reproduced.

Where do by-products originate and what determines their value?

Where do by-products originate and what determines their value? The cherry supply chain is characterized by critical points where by-products and losses arise. Fruit is subject to strict quality standards; therefore, waste is associated with mechanical damage (cracks or splits), sizes below commercial standards and post-harvest losses linked to handling, transport and storage.

In producing regions, very high losses have been reported under unfavorable conditions; in terms of total waste generation, the literature summarized in this review estimates that figures may reach up to around 30% of production.

In addition to discarded fruit, there are structural fractions derived from processing. Pomace appears in processes such as juice production; stems are removed during conditioning or prior to consumption; and pits are separated in some processing methods.

From a quantitative standpoint, stems and pits account for between 15% and 16% of fruit weight, a proportion sufficient to influence collection logistics and process design if industrial-scale valorization is intended.

This article by Farias et al. (2025) groups these streams as cherry by-products (CBP). This classification is useful because it anticipates composition: stems tend to concentrate phenolic compounds; pits combine a lipid fraction with bioactive molecules; and pomace, dominated by skin, concentrates anthocyanins.

The real value, however, depends on variability (cultivar, environment, maturity) and on the ability to standardize by-product batches so that industry can operate with reproducible specifications. In other words, value creation begins with characterization, but is consolidated through quality control and traceability of the raw material.

Phytochemical composition and bioactive potential

Cherry biomass substances (CBS) are a rich source of phytochemicals with biological activity. This potential is not evenly distributed: each fraction contains distinct chemical families and therefore supports different applications.

This understanding avoids designing a single solution for the residue and helps set priorities in technological decisions: which fraction to recover first, which compounds to target and which pathways make sense in terms of performance, stability and market relevance.

Figure 2. “The contribution of each fraction”. Visual summary of stems, pits and pomace with key compounds and reported quantitative ranges. Credits: author’s elaboration (synthesis). Source: review by Farias et al. (2025) and studies cited therein. No graphical material from the original article is reproduced.

Figure 2. “The contribution of each fraction”. Visual summary of stems, pits and pomace with key compounds and reported quantitative ranges. Credits: author’s elaboration (synthesis). Source: review by Farias et al. (2025) and studies cited therein. No graphical material from the original article is reproduced.

Stems: polyphenols and tocopherols

Stems are described as having a matrix particularly rich in phenols and flavonoids, with reported total phenolic values ranging from 26.6 to 32.4 mg GAE/g and total flavonoids between 13.1 and 24.75 mg EC/g (Farias et al., 2025).

Molecules of interest include catechin and epicatechin; phenolic acids such as ellagic, ferulic and syringic acids; and flavonoids such as quercetin and naringin. Organic acids (oxalic, malic and citric acids) are also mentioned, relevant for their potential impact on extract behavior and compatibility with certain applications.

The most striking element is the presence of tocopherols at concentrations about five times higher than those found in the fruit. This detail changes the interpretation of stems: in addition to polyphenols, they can provide lipophilic antioxidants, opening the way to processes aimed at fractionation and recovery of specific chemical families.

From an industrial perspective, this fraction could be considered a priority when the objective is to obtain extracts with antioxidant and potential antimicrobial activity and when a clear end-use pathway exists (food, cosmetics or functional formulations).

Pits: oil and a high-value unsaponifiable fraction

Pits contain a high concentration of phenolic compounds (vanillic acid, epicatechin, catechin, isoquercetin and rutin) and a significant lipid fraction. Oil can account for between 25% and 30% of pit dry weight, with a predominance of oleic and linoleic acids.

The value of the oil is further enhanced by its unsaponifiable fraction: β-sitosterol may represent more than 80% of the sterol fraction, and α-tocopherols are cited as natural antioxidants.

The practical implications are twofold. On the one hand, pits enable pathways focused on ingredients (oil and bioactives) with nutraceutical or cosmetic applications, particularly if efficient extraction and a stable profile are achieved.

On the other hand, the post-extraction solid residue opens the way to material valorization (for example, carbon-based materials), compatible with a complete biorefinery approach.

Pomace: anthocyanins and phenolics as functional support

Pomace (skin and press cake) is the fraction most closely associated with anthocyanins. Total anthocyanins of 12.2 ± 0.5 mg C3G/g and total phenolics of 445.93 ± 5.11 mg GAE/g have been reported.

The main anthocyanin is cyanidin 3-rutinoside, followed by cyanidin 3-glucoside and others in smaller proportions. This profile suggests a clear use: natural colorants and extracts with antioxidant functionality.

The challenge is technological: anthocyanin stability depends on formulation and environment (pH, light, oxygen and other factors), so industrial success depends not only on “large-scale extraction” but on obtaining a stable extract compatible with the final application.

The article also highlights that cherry pomace has been less explored than that of other closely related species, leaving room for yield optimization, stabilization and scale-up using green chemistry principles.

Extraction technologies and solvent selection

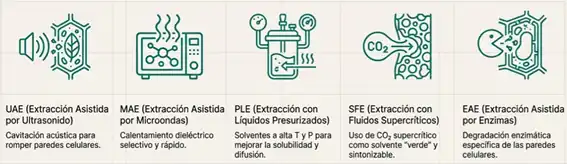

The recovery of bioactive compounds requires efficient and sustainable processes. Conventional methods (maceration, Soxhlet extraction, mechanical stirring) offer simplicity, but often involve long processing times, limited selectivity and high solvent consumption.

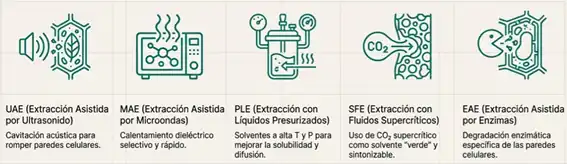

By contrast, non-conventional or “green” technologies (PLE, SWE, SFE, MAE, UAE, EAE) aim to reduce processing time, solvent consumption and energy use, improve yields and preserve thermosensitive compounds.

The identified opportunity is clear: shift technological development toward more efficient pathways with reduced environmental impact, without compromising extract quality.

Figure 3. “Non-conventional extraction technologies”. Comparative overview of UAE, MAE, PLE, SFE and EAE, highlighting mechanisms and links to the objective of reducing solvents, time and energy. Credits: author’s work (synthesis). Source: review by Farias et al. (2025) and studies cited therein. No graphical material from the original article is reproduced.

Figure 3. “Non-conventional extraction technologies”. Comparative overview of UAE, MAE, PLE, SFE and EAE, highlighting mechanisms and links to the objective of reducing solvents, time and energy. Credits: author’s work (synthesis). Source: review by Farias et al. (2025) and studies cited therein. No graphical material from the original article is reproduced.

Sustainable solvents

The solvent influences cost, safety and acceptability of the extract. Accordingly, selection guidelines based on environmental, health and safety criteria have been developed to justify decisions and guide processes toward lower-risk profiles.

The article also mentions emerging solvent families such as ionic liquids (IL) and deep eutectic solvents (DES), highlighting their low volatility and potential to tune selectivity.

In practice, their suitability should be assessed case by case, considering composition, toxicity, biodegradability and recovery potential, especially if the final product is intended for food or cosmetic use.

Furthermore, the review highlights an underutilized research area in this context: the use of in silico predictive tools to guide solvent selection prior to experimentation. Models such as COSMO-SAC allow estimation of theoretical affinity and solubility, thereby reducing iterations, reagent consumption and development time.

The review emphasizes that, for cherry biomass substances (CBS), this approach has not yet been systematically applied, representing a methodological opportunity: designing extraction processes more rationally from the outset, with fewer trial-and-error steps, aligning performance and sustainability from the earliest stages.

Biological properties and applications

Their exceptional biological activities – antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial – support industrial interest. Antioxidant activity is quantified using DPPH, with an IC50 of just 3.97 mg/mL in the Van variety (Acero et al., 2019, cited in Farias et al., 2025), as an example of relative potency.

Anti-inflammatory activity is described as modulation of nitric oxide (NO) and suppression of mediators such as iNOS and COX-2. Antimicrobial activity has also been reported against Gram-positive bacteria (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus cereus) and Gram-negative bacteria, associated with phenolic content.

Translation into applications can be organized by sector: food, natural preservatives, functional ingredients and anthocyanin colorants; nutraceutical/pharmaceutical, dietary supplements and topical formulations; cosmetics, anti-aging and photoprotective formulations; and agricultural/environmental applications, including biopesticides, biofertilizers and effluent treatment solutions.

The article also adds an emerging field: biodegradable smart packaging with halochromic and antioxidant functionality, an idea closely linked to the behavior of anthocyanins as environmentally sensitive pigments.

LCA and TEA: turning potential into viable solutions

The circular economy requires verification of environmental sustainability and economic feasibility. Life cycle assessments (LCA) and techno-economic analyses (TEA) are used for this purpose.

This article identifies a gap: LCA/TEA studies specifically focused on the production of bioactive and nutraceutical compounds from cherry biomass substances (CBS) remain scarce, limiting objective comparison of technological pathways and their industrial prioritization.

In practice, this lack of data makes it difficult to answer very specific questions: what is the most appropriate functional unit (e.g. per kilogram of standardized extract), how impacts are allocated in the presence of co-products, or what share of total cost is attributable to energy, solvent, drying and purification.

Despite this limitation, illustrative examples are described. Activated carbon production from pits could be associated with lower environmental impact and savings of up to USD 229 (approximately EUR 210)/kg (Vukelic et al., 2018, cited in Farias et al., 2025), with direct applications in industrial wastewater treatment.

The conversion of pits into biochar is proposed as a way to improve soils and contribute to remediation, as well as serving as a carbon sink. Finally, the use of stem and pit extracts as natural coagulants in industrial effluents is shown to be a low-cost alternative, achieving turbidity reductions of 78.6% and TSS reductions of 68.2% (Teixeira et al., 2024, cited in Farias et al., 2025).

These cases also broaden the strategy: not all pathways need to be “premium”; robust valorization can combine a high-value fraction (bioactives) with a volume output (materials/environmental) to balance economics, logistics and sustainability.

Four priorities to make valorization real

Cherry by-products – stems, pits and pomace – contain bioactive compounds and technological pathways that can potentially create high value-added products and reduce the environmental impact of the supply chain.

To realize this potential, the article focuses on four priorities: (1) prioritizing green technologies and combining them efficiently to maximize yield and preserve thermosensitive compounds; (2) adopting a complete biorefinery that utilizes all waste fractions; (3) overcoming barriers to industrial implementation; (4) integrating sustainability (LCA) and feasibility (TEA) assessments into process design.

Ultimately, cherry competitiveness is not determined solely by the commercial fruit: it also depends on the ability to transform a by-product stream that can reach 30% of the biomass associated with the supply chain into economically meaningful ingredients, materials and solutions within a circular bioeconomy.

Images source: Jesus Alonso

Jesus Alonso

EL MUNDO DE LAS CEREZAS

Editor’s note This article summarizes and contextualizes, from a circular economy perspective, the key messages of the review by Farias, Muchanga and Mussagy (2025) on the potential of sweet cherry by-products to recover bioactive compounds and generate new industrial value chains.

Source: Farias, F.O.; Muchanga, F.J.; Mussagy, C.U. (2025). Potential of sweet cherry by-products: From agro-industrial residues to the sustainable recovery of bioactive compounds in a circular economy framework. Food and Bioproducts Processing, Volume 153, pp. 173–184.

Cherry Times – All rights reserved