Sweet cherry bacterial canker is a dangerous disease that can cause significant economic losses. A recent study analyzed the diversity of Pseudomonas syringae sensu lato, a complex of bacteria known for their pathogenicity in plants, present in California.

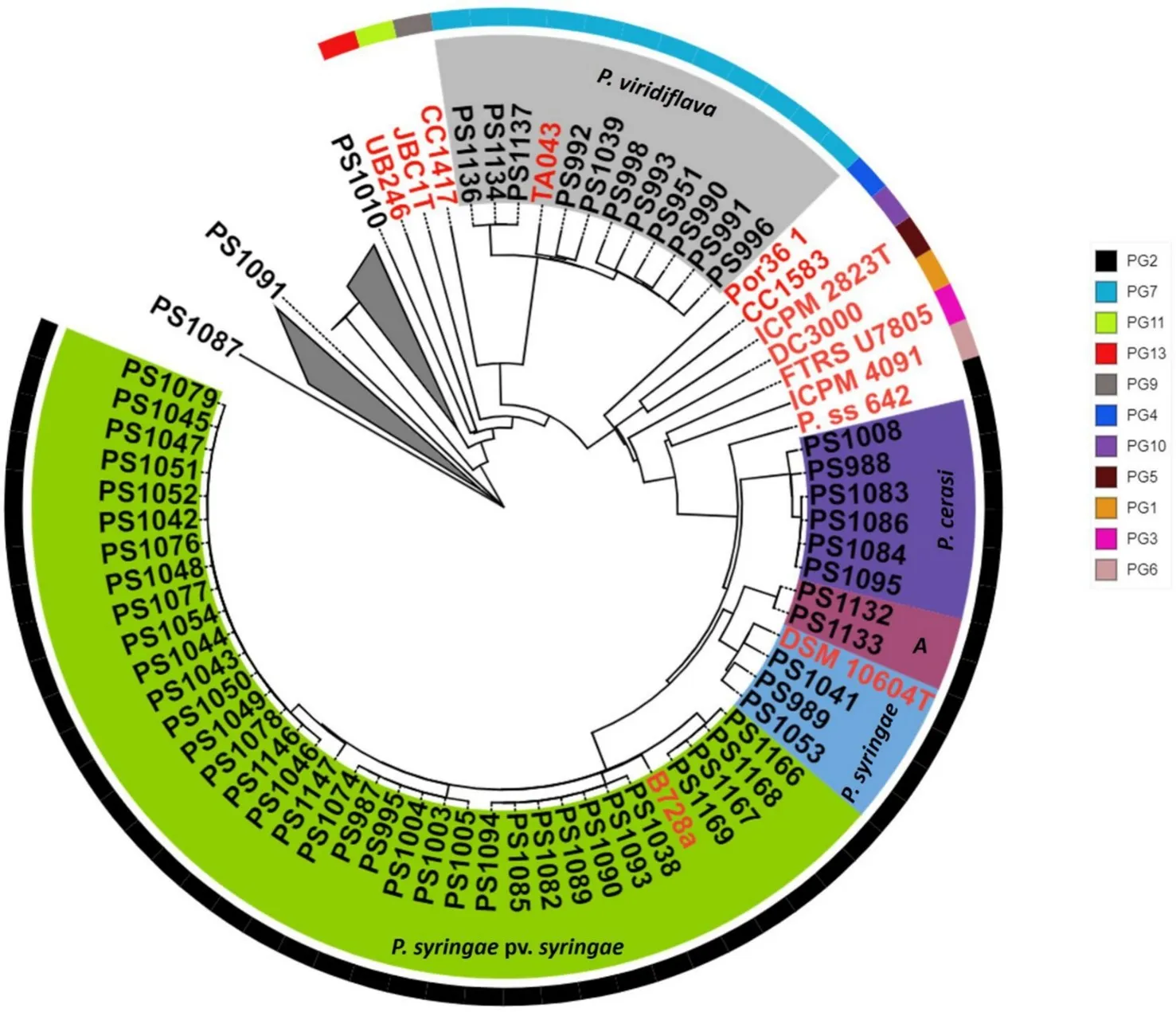

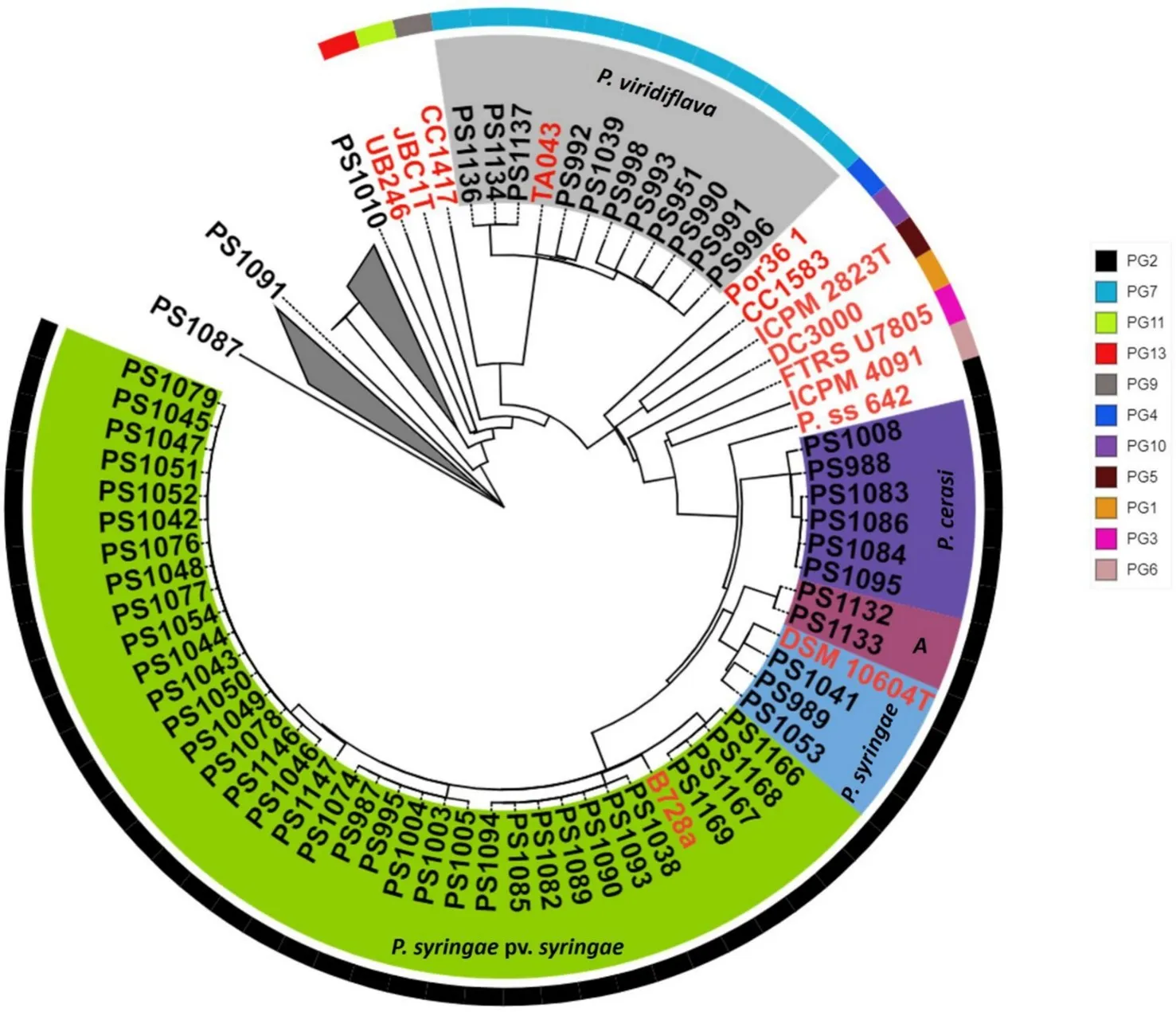

By sequencing the genome of 86 isolates obtained from both symptomatic and asymptomatic fruit, 58 were phylogenetically placed within the P. syringae species complex and taxonomically classified into five genomospecies: P. syringae pv. syringae, P. syringae, P. cerasi, P. viridiflava, and an additional genomospecies designated as "A."

The analysis revealed that only some genomospecies were effectively pathogenic. P. syringae pv. syringae emerged as the primary cause of the most severe symptoms, including branch cankers, leaf spots, and fruit lesions, and was also the most frequently isolated genomospecies. In contrast, P. cerasi and P. viridiflava exhibited reduced pathogenicity, while genomospecies "A" caused no evident symptoms, suggesting that phytotoxins are essential for pathogenicity.

Image 1: Symptoms of bacterial blast and bacterial canker on sweet cherry. (A) Trunk canker with amber-colored gumballs on the margins. (B) Blasted flowers; they turn brown and wither while still attached to the plant. (C) Dead buds with amber-colored gumming exuding from the base of a dead spur; the bacteria are most likely initiating branch canker. (D) Typical fruit rot caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae showing a sunken black–dark brown lesion. Source: Maguvu et al., 2024.

Image 1: Symptoms of bacterial blast and bacterial canker on sweet cherry. (A) Trunk canker with amber-colored gumballs on the margins. (B) Blasted flowers; they turn brown and wither while still attached to the plant. (C) Dead buds with amber-colored gumming exuding from the base of a dead spur; the bacteria are most likely initiating branch canker. (D) Typical fruit rot caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae showing a sunken black–dark brown lesion. Source: Maguvu et al., 2024.

Phylogenomic analyses did not identify P. syringae pv. morsprunorum (now P. amygdali pv. morsprunorum) and P. avellanae, previously reported in sweet cherry, suggesting these may not be present in California. However, it is possible that these genomospecies were simply missed during isolation.

The study followed a combined approach of genomic analysis and field pathogenicity tests. While laboratory tests are useful for identifying pathogens, they tend to overestimate the ability of organisms to cause disease due to the optimal growth conditions present in the lab. Field results demonstrated that only certain genomospecies were capable of causing significant infections.

Image 2: Detached immature fruit pathogenicity test. Rating scale for lesions/rot on the fruits. The image shows severity score ratings (0-5) from left to right. Source: Maguvu et al., 2024.

Image 2: Detached immature fruit pathogenicity test. Rating scale for lesions/rot on the fruits. The image shows severity score ratings (0-5) from left to right. Source: Maguvu et al., 2024.

In particular, P. syringae pv. syringae showed a high infection capacity, while other genomospecies required specific conditions, such as wounds or higher temperatures, to exhibit pathogenicity. Additionally, several genomospecies produce syringomycin and syringopeptin, essential toxins for pathogenicity, except for P. viridiflava and "A", which did not have the genes to encode them. This also explains their lower virulence observed in the field.

The study also investigated resistance genes. Results showed a high level of copper resistance among P. syringae pv. syringae isolates (47.5%), making this compound ineffective for disease management. However, no isolates exhibited resistance to kasugamycin (antibiotic).

Image 1: A close-up of the phylogenomic analyses of the P. syringae species complex from Fig. 3. Isolates from this study are highlighted in black, and isolates highlighted in red are representatives of the established P. syringae phylogroups. Isolates from this study fall into two main phylogroups (PG) PG2 and PG7 (see key). They were taxonomically classified into at least five genomospecies based on dDDH; P. syringae pv. syringae, P. syringae, A, P. cerasi, and P. viridiflava. Source: Maguvu et al., 2024.

Image 1: A close-up of the phylogenomic analyses of the P. syringae species complex from Fig. 3. Isolates from this study are highlighted in black, and isolates highlighted in red are representatives of the established P. syringae phylogroups. Isolates from this study fall into two main phylogroups (PG) PG2 and PG7 (see key). They were taxonomically classified into at least five genomospecies based on dDDH; P. syringae pv. syringae, P. syringae, A, P. cerasi, and P. viridiflava. Source: Maguvu et al., 2024.

These findings highlight the need for integrated management strategies that consider the pathogens diversity present in the orchards. Understanding the biology of different bacterial strains will allow the development of specific agronomic practices to limit disease spread and protect California sweet cherry orchards from bacterial canker.

From an application standpoint, disease management should include constant monitoring of resistance and prudent use of active ingredients. Finally, promising future opportunities for sweet cherry cultivation should include the use of tolerant or resistant cultivars to help reduce disease spread, as well as the adoption of biocontrol strategies, such as the use of antagonist bacteria or plant resistance inducers.

Source: Maguvu, T. E., Frias, R. J., Hernandez-Rosas, A. I., Shipley, E., Dardani, G., Nouri, M. T., Yaghmour, M. A. & Trouillas, F. P. (2024). Pathogenicity, phylogenomic, and comparative genomic study of Pseudomonas syringae sensu lato affecting sweet cherry in California. Microbiology Spectrum, 12(10), e01324-24. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.01324-24.

Images: Maguvu et al., 2024.

Andrea Giovannini

University of Bologna (IT)

Cherry Times - All rights reserved