A well-managed cherry orchard will continue to be a great business, says consultant Christian Gallegos. He has developed a model that allows producers to make projections and encourages them to examine it with their own numbers, in order to understand where they stand and thus make the right decisions.

He advises paying attention to the practices that generate greater value, as well as avoiding the temptation to save in ways that would reduce the production of target fruit, increase the cost per kilo, decrease the return per kilo or both.

Analysis based on data

Analysis based on data from real cases

How to move from cost to value in cherry orchards

A well-managed cherry orchard will continue to be a great business, says consultant Christian Gallegos. He has developed a model that allows producers to make projections and encourages them to examine it with their own numbers, to understand where they stand and thus make the right decisions.

He advises paying attention to practices that generate greater value, as well as avoiding the temptation to save in ways that would reduce the production of target fruit, increase the cost per kilo, decrease the return per kilo, or both.

The situation of the cherry sector

“The queen of Chilean fruits is going through a tough moment,” observes Christian Gallegos, cherry and blueberry consultant, founder of BerryCherry and technical director of Crop Solutions, referring to last season’s commercial results.

However, to avoid being dragged down by pessimism, he summarizes the sector’s situation this way:

Chile is the world’s most important exporter and accounts for 97% of the counter-season market in 2024/25, with a huge lead over southern hemisphere competitors such as Argentina, Australia, New Zealand, or South Africa. In the last season, 630,000 tons were shipped, equivalent to 125 million 5-kg boxes.

“Ninety-one percent of our fruit goes to China; we are dependent on China and will be for a long time,” says Gallegos. “If we redistributed another 10% of our supply to other markets, I believe we would saturate them. In 20 years, our supply has increased by 2,861% and in the last decade by 507%.”

Varieties and expansion

“The closest case to this explosive growth is that of blueberries in Peru. The most important varieties are Lapins (29,000 ha), Santina (20,000 ha) and Regina (11,500 ha). These are followed, in decreasing order of presence, by Bing, Kordia, Sweetheart, Royal Dawn, Skeena, Rainier, Sweet Aryana and others. In total, around 82,000 hectares planted are estimated.”

Christian Gallegos

Christian Gallegos

The consultant mentions new cultivars entering the southern zone:

Final 12 and Final 13, from the Peter Stoppel group (intended for areas from Collipulli-Traiguén southward). In Purranque they are harvested 10–12 days later than Regina. It is important to keep in mind that the only period when there are no cherries in the world is March–April, except for greenhouse production in China, which begins in mid-April.

Sweet Saretta, from the University of Bologna breeding program, similar to Lapins.

Areko (Regina-Kordia cross), from the Julius Kühn Institute (JKI), already planted on several hectares in Biobío “and it works very well.”

It is estimated that around 82,000 hectares are planted with cherry trees and that another 2,500–3,000 hectares were planted this season.

It is estimated that around 82,000 hectares are planted with cherry trees and that another 2,500–3,000 hectares were planted this season.

Context and challenges for the season

The technical director of Crop Solutions highlights a significant national figure:

“This season, despite recent problems, around 2,500–3,000 hectares were still planted. They will likely start removing cherry orchards that no longer perform well and replacing them with new plantings.”

For the 2025/26 season, during the initial harvest phase at the time of publication, he indicates the need to keep the following factors in mind:

China is experiencing a slowdown in economic growth, and it is possible that cherry supply has exceeded demand in that market.

It is necessary to avoid sending inconsistent fruit, with defects such as low sugar content, lizard skin, pitting, and dehydrated stems.

Chinese New Year will fall on February 17 (in 2025 it was January 29). This date “moves the phenology of the plants,” says Gallegos metaphorically: the earlier it is, the more production tends to advance; the later it is, the more it tends to be delayed.

Harvest forecasts

“Phenology largely depends on the accumulation of degree days, which this year was higher than normal, accelerating budbreak and flowering. However, there were weekly rains and thermal fluctuations in September, so phenology slowed down. Flowering periods were more extended, which will result in heterogeneous fruit maturation; I therefore expect a long season.”

Santina is expected to begin entering strongly in week 49, although with a light load that eases peak weeks (50–52), flattening the supply curve.

In December, the major challenge of managing around 5,200 containers per week will likely return, a task the industry handled adequately last year.

At the peak in week 50, the forecast is 35% Santina, 50% Lapins, 10% Regina, and 5% other varieties.

At 3.0 USD/kg, with 14,000 kg/ha, cultivation becomes highly profitable.

At 3.0 USD/kg, with 14,000 kg/ha, cultivation becomes highly profitable.

Liquidations and costs offer a revealing insight

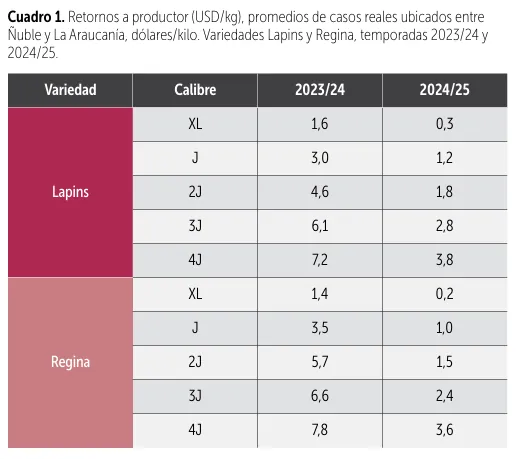

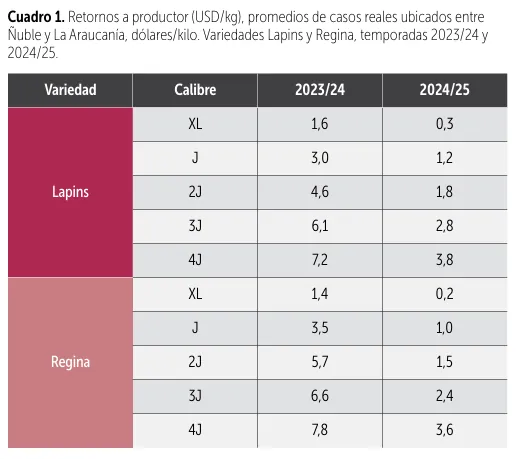

The consultant gathered real liquidation data from producers in Ñuble, Biobío, and Araucanía. Table 1 presents the average producer return per kilo for Lapins and Regina varieties in the last two seasons. He highlights the drop in value for XL caliber, which fell from 1.6 and 1.4 USD (1.47 € and 1.29 €) to 0.2 and 0.3 USD (0.18 € and 0.27 €), figures he considers “somewhat polished, because they include cases with minimum guarantees from exporters.”

His perception is that the vast majority of XL caliber fruit had negative returns, around -5 to -7 cents/kg.

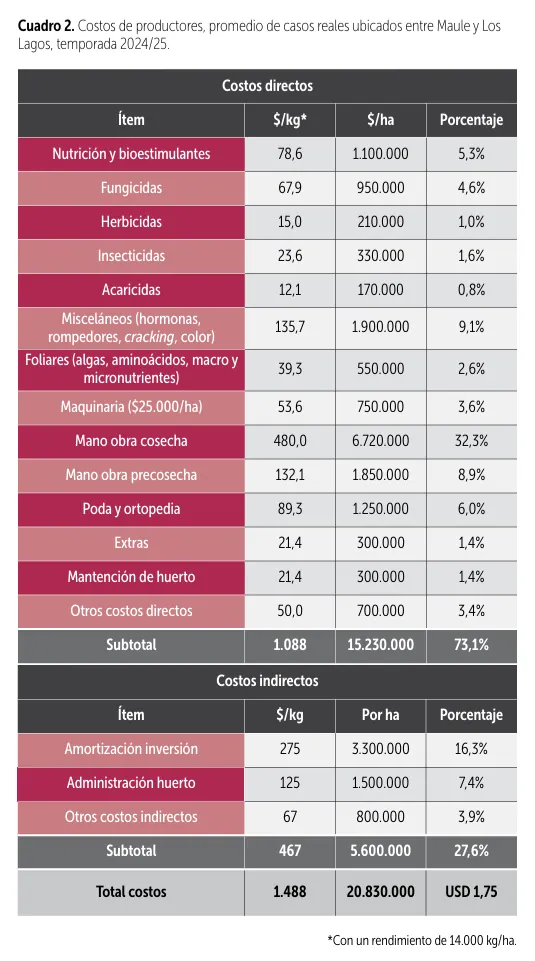

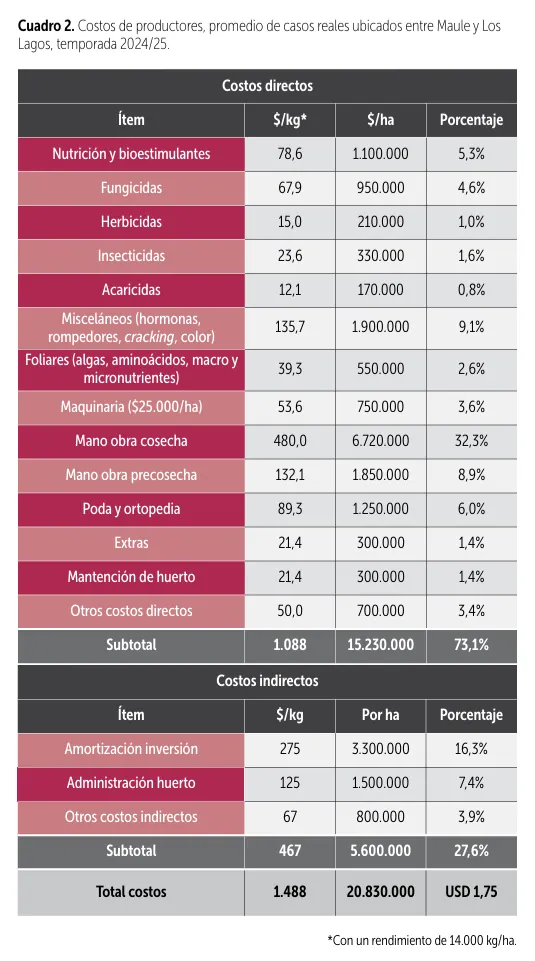

Christian Gallegos also gathered cost data from his producers between the Maule and Los Lagos regions, whose average values are reported in Table 2. He highlights that the cost of harvest labor alone represents almost one third of the total (32%; 6.7 million pesos/ha, around 7,882 €).

Grouped inputs, including machinery for application and other operations, account for around 25% of the total (5.2 million pesos/ha, around 6,117 €).

Composition of production costs

The consultant groups the remaining items under “farm management,” including pre-season labor, at 43% (8.9 million pesos, around 10,475 €).

Since the calculation of “machinery” costs is often difficult to include in the financial statement, the technical director of Crop Solutions assigns it a value equivalent to hiring a service provider.

Investment depreciation was projected over 12 years. Land cost and potential major infrastructure needs, such as a water reservoir, were not included.

Naturally, figures vary according to each orchard’s conditions and each season, potentially being higher in one category and lower in another. A single average value will hardly match every specific reality, but the provided data can serve as a reference to adjust according to the specific conditions of an orchard.

Producer returns (USD/kg), averages of real cases between Ñuble and Araucanía, dollars/kilo. Lapins and Regina varieties, 2023/24 and 2024/25 seasons.

Producer returns (USD/kg), averages of real cases between Ñuble and Araucanía, dollars/kilo. Lapins and Regina varieties, 2023/24 and 2024/25 seasons.

Scenarios with different prices and production

For example, self-fertile varieties will probably require less expensive hormones than those needing synchronization with pollinizers.

Assuming that harvest labor costs vary proportionally with kilos harvested and that other costs remain unchanged, Gallegos performs a sensitivity analysis on different price and production scenarios per hectare (Table 3).

The calculation is based on an export percentage of 85% and assigns a cost of -1 dollar (around -0.92 €) per kilo of cherries for the 15% that are processed but not exported.

“Fruit that does not make it into a box means losing production, harvest, and packing costs.”

He assumes 16,500 USD (approx. 15,153 €) for all costs other than harvest labor, as reported in Table 2, converted into dollars with a conservative exchange rate estimate of 850 pesos per dollar.

The turning point for profitability

According to the results in Table 3, an orchard with yields of 8,000 kg/ha exits the business unless its liquidation price is around 3.5 USD/kg (around 3.21 €/kg) or higher.

“How many orchards yielding 4,000, 5,000, 6,000 kg/ha are still hanging on?” asks the specialist.

“I’m talking about old orchards, planted around the year 2000, often with poor practices, unsuitable variety-rootstock combinations, inadequate zoning… When producers were receiving 5.0 USD/kg (4.59 €/kg) they were sustainable, but not with returns of 2.5 to 3.5 USD.

If we consider 3.0 USD/kg (2.75 €/kg), the productivity threshold at which profits begin is 10,000 kg/ha, and with 14,000 kg/ha cultivation becomes highly profitable. In the future the business will likely stabilize between 10,000 and 15,000 USD/ha (between 9,180 € and 13,770 €); few agricultural alternatives in Chile come close to that.”

Uneven impact of the crisis

In his view, the current crisis does not affect everyone equally:

“Those who planted in 2010 faced the COVID crash with their orchards already paid off. If they were orderly, I’d say they are not in a bad situation today. Those who started harvesting between 2018 and 2020 and are still amortizing the orchard took a hard hit this season.”

Producer costs, average of real cases between Maule and Los Lagos, 2024/25 season.

Producer costs, average of real cases between Maule and Los Lagos, 2024/25 season.

Practices that add value

“Is it possible to reduce costs? What is your recommendation?”

“You can reduce them with more fruit of good caliber. As shown in Table 3, with 8,000 kg/ha the cost per kilo is 2.62 USD (2.41 €); with 18,000 kg/ha it drops to 1.48 USD/kg (1.36 €/kg). Very often it is more efficient to increase production of target fruit by 10% than to reduce total costs by 10%. The key is being more productive.”

Gallegos warns about the risk of misguided savings, because they affect production, and stresses the importance of giving priority to practices that add value:

“For example, if a producer tells me they have reduced pruning costs because they found a cheaper contractor, I ask them to check how many people change every day, whether they come from the municipality pruning poplars their whole lives, and whether any preliminary training was provided.

You might spend 2 or 3 years recovering the rows where they left trees reduced to a minimum, before rebuilding vegetative centers and lignifying that structure. Pruning, crop load regulation and orchard architecture, as well as all important practices, must be done correctly and with close supervision.”

Effectiveness with efficiency

He also advocates “effectiveness with efficiency” in production systems. He gives an example:

“How do I reduce the costs of my phytosanitary program and foliar treatments? By carrying out the same applications but adjusting the spray volume. There are orchards where 1,500 liters of water are applied each time, when perhaps they should be 700 liters at flowering and 1,000 liters in full production.

Just this would reduce the phytosanitary program by 30%, considering that many recommendations are based on hectoliters.”

Finally, the consultant encourages producers to carry out the analysis with their own costs and production:

“It is an exercise worth doing to understand where you stand, especially when you have to make decisions such as ‘Should I uproot an orchard or not?’.”

Estimated economic result across different production scenarios per hectare and net producer return per kilo of cherries.

Estimated economic result across different production scenarios per hectare and net producer return per kilo of cherries.

Source text and images: Redagricola Team

Cherry Times - All rights reserved