Michigan State University researcher urges cherry industry to use technology to measure leaf-to-fruit ratio for crop load management.

Greg Lang, professor emeritus of Michigan State University, discusses the changing horticultural strategies of tree fruit during his Batjer Address at the Washington State Tree Fruit Association’s annual meeting in December in Wenatchee, Washington. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Greg Lang, professor emeritus of Michigan State University, discusses the changing horticultural strategies of tree fruit during his Batjer Address at the Washington State Tree Fruit Association’s annual meeting in December in Wenatchee, Washington. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

The ratio of leaf surface area to fruit is a key measurement to inform horticultural management of sweet cherries. Greg Lang has focused on this since first running with the idea in the mid-1990s as growers adopted dwarfing rootstocks.

“Leaf-to-fruit ratio has informed everything from that point on,” said Lang, professor emeritus at Michigan State University. The advent of high-capacity imaging sensors might make this a good time for growers to use the research metric for management decisions.

Lang discussed leaf-to-fruit ratio as just one chapter of his 100-slide Batjer Address, the scientific keynote of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association Annual Meeting, held in December in Wenatchee.

The history-encompassing discussion covered how wild cherry trees grow to 130 feet (39.6 meters) in the forest, the introduction of dwarfing rootstocks and how AI-powered scanning has begun measuring everything from buds to canopy to trunk diameter.

Lang, the education director for the International Fruit Tree Association, also talked about how growers transitioned apple, peach, cherry and plum trees from three-dimensional vase shapes to narrow, two-dimensional fruit walls. When a tree is planar, a greater percentage of its leaves are in position to absorb light, the most important input for any plant and the only one that’s free for a farmer.

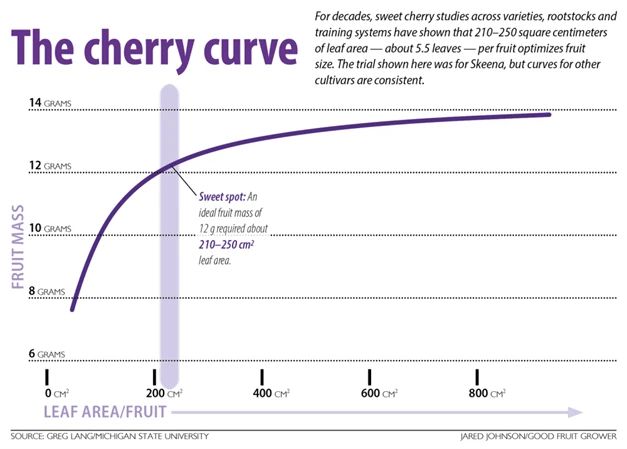

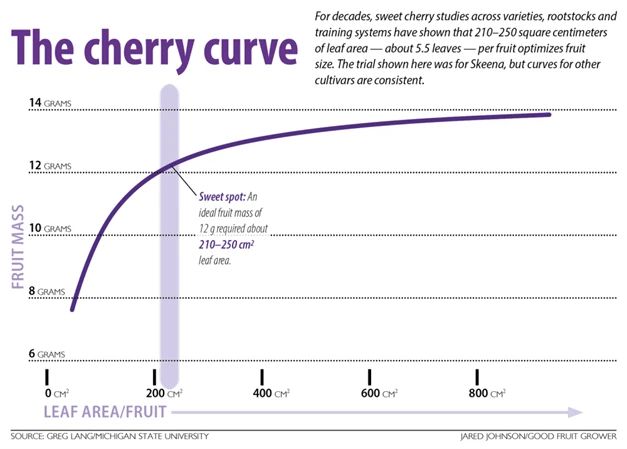

For decades, sweet cherry studies across varieties, rootstocks and training systems have shown that 210 to 250 square centimeters of leaf area — about 5.5 leaves — per fruit optimizes fruit size. Beyond that, the fruit’s growth curve starts to flatten. More specifically, the spur leaves contribute the most toward fruit size and sweetness, two key quality indicators.

New shoot leaves don’t help as much. In fact, shoot leaves could shade the more important spur leaves. He calls that the physiological reason to consider hedging of planar canopies. Research suggests to him that the high proportion of sunlit leaves in a narrow, planar canopy maximizes photosynthesis at only 45 to 55 percent of full sunlight, regardless of climate.

The rest of the sunlight is extra, so shading by rain or hail covering may not hurt. In fact, he thinks the industry should explore agrivoltaics, putting solar panels over the rows to harvest some of that extra sunshine for electricity. “We’ve still got a lot of sunlight that we’re not using,” he said. The problem is that leaf-to-fruit ratio has been hard to measure, making it an impractical tool for horticultural management.

Instead, growers use imperfect proxies, such as trunk cross-sectional area, spurs per branch or flowers per bud. Imaging sensors could solve that problem, Lang said. The cameras and artificial intelligence algorithms increasingly count buds, fruit and branches. Why not program them to quantify sunlit leaf area, too? “Right there you’ve got leaf-to-fruit ratio,” Lang said.

A chart showing the correlation of leaf area per fruit and fruit mass based on research from Greg Lang at Michigan State University and Denise Neilsen, Gerry Neilsen and Tom Forge at the Summerland Research and Development Centre in British Columbia, Canada. (Source: Greg Lang/Michigan State University; Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

A chart showing the correlation of leaf area per fruit and fruit mass based on research from Greg Lang at Michigan State University and Denise Neilsen, Gerry Neilsen and Tom Forge at the Summerland Research and Development Centre in British Columbia, Canada. (Source: Greg Lang/Michigan State University; Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

The tech potential

Steve Mantle, CEO of innov8.ag, thinks Lang might be onto something. Some imaging companies’ sensors already collect a measurement they call leaf-area index. His company, an ag tech service provider, has done so during trials, while orchardists in New Zealand and Australia use that metric in management. Green Atlas, the Australian technology that innov8.ag uses, has a white paper about calculating “fruit per canopy leaf-area.”

Mantle envisions using the data in the United States to designate high, medium and low canopy areas so orchardists could variably manage crop load, much the way some now do with variable-rate sprayers and fertilizer spreaders. The trick would be getting managers to accept the measurement as a valid tool.

“What isn’t out there is this commonly accepted approach to using the ratio of tree fruit to leaf area index as a management approach,” he said. “And it should be.”

A physiologist on practicality

Matt Whiting, Washington State University tree fruit physiologist, was Lang’s graduate student and helped his mentor count a lot of leaves in the name of research. As far as Whiting knows, no cherry grower uses leaf-to-fruit ratio to inform horticultural decisions. “In practical terms, it’s useless,” Whiting said.

He’s not sure sensors would make the difference, either. Engineering camera systems to recognize leaves occluding leaves occluding more leaves, as well as distinguishing between spur and shoot leaves, would be a challenge.

That doesn’t mean the metric is a pointless discussion, though, Whiting said. He sometimes discusses leaf area during field days, while growers sometimes do measure fruit buds per foot of bearing limbs. It’s an imperfect proxy for leaf-to-fruit ratio, but it’s an upgrade over trunk cross-sectional area, he said.

Cherry industry leaders have been suggesting that growers use aggressive pruning to reduce tons per acre (1 ton/acre ≈ 2.24 metric tons/hectare) and improve size and quality across the industry. Remembering that leaves fuel fruit development should underpin all of those decisions, Whiting said, even if it’s impractical to count leaves.

A grower view

Allan Bros. horticulturists in Washington’s Yakima Valley don’t really discuss leaf-to-fruit ratio, but other metrics accomplish the same goal, said Travis Allan, director of tree fruit. They count practically every other ratio — flowers per bud, buds per spur, spurs per branch and branches per tree.

They combine those averages with their historical knowledge of production for each block to target a yield that will produce cherries of at least 10.5-row size for all varieties. They handle as much as they can with winter pruning and sometimes check their work by counting cherry-growing points per foot of productive wood.

They aim for 30 to 35 with Rainiers and 40 to 50 for the dark red varieties. If they have too many, they send crews to remove spurs and buds by hand, a time-consuming chore. Allan is skeptical of scanners counting cherries or leaves accurately. If anything, they could help him and his managers identify nonproductive branches and target them for renewal pruning. “That would help me,” he said.

Lang responds

Any adoption of new technology and techniques comes with challenges, but these are surmountable, Lang said. As long as a planar canopy has filled its space, and as long as the orchard is managed correctly, the sunlit leaf area — and thus estimated target crop load — remains constant, Lang said.

Occluded leaves decrease as canopies become narrower, he said. Also, timing matters. Imaging a few weeks after budbreak, when spur leaf expansion is complete and new shoot growth is minimal, would quantify the most significant leaf area that ultimately will support the targeted crop load.

Lang doesn’t doubt that good growers, like Allan Bros., perform well with labor-intensive methods, such as physically counting all those other metrics, but part of a scientist’s job is to help growers find more efficient and more precise techniques, he said. Pairing leaf-to-fruit ratio with AI imaging could offer that.

“We’ll see where the leaf-area imaging technology is in a couple of years and then see what Travis thinks,” Lang said.

Watch the video and learn as Greg Lang discusses the complexities of the leaf-fruit relationship

Ross Courtney

Associate editor for Good Fruit Grower

Cherry Times - All rights reserved