It is urgent to acquire the discipline needed to become more efficient. This does not necessarily mean cutting costs, but rather investing money productively to achieve the main goal: obtaining better prices.

We must not forget that larger calibers have always commanded higher prices. Since the cherry production boom targeting the Chinese market began, the first boxes of the Bing variety opened the doors to the Far East.

Until now, demand for our product has always been high and — of course — so have the returns, as we are the only ones able to supply cherries during the Chinese New Year celebrations.

This demand has led us to surpass 70,000 hectares planted, with positive results but also many mistakes. Ill-conceived projects were launched, low-quality trees planted, varieties grown in unsuitable areas, and occasional investors attracted by the profits this sector had offered until recently.

How we reached 125,000,000 boxes

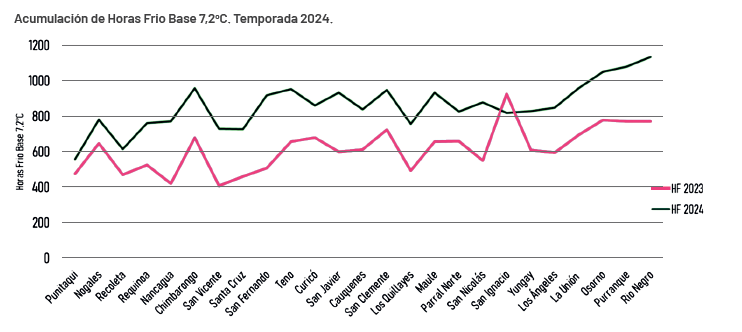

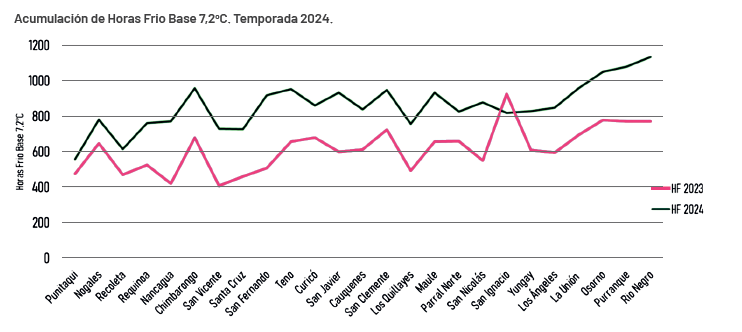

To go from 83 million boxes last season to 125 million in 2024, several factors aligned that directly affected production increases or decreases.

The most relevant include: low productivity in 2023 due to insufficient winter chill, which allowed orchards to be more “rested” for the 2024 season.

The summer of 2024, especially January, brought lower temperatures ideal for flower induction and differentiation. The winter of 2024 was one of the best in terms of accumulated chill hours.

Increased bud/dart fertility, with more blossoms per fruiting center. Low intensity in crop load regulation — especially pruning — due to fears of issues like flower abortion or frost.

No rain issues during spring flowering and fruit development, which could have affected quality, especially in terms of fruit cracking.

The time for discipline has come

In light of last season, we are now facing a turning point in cherry production. Overproduction, a high volume of small-sized fruit, and quality defects such as rot and physiological disorders — combined with declining domestic consumption in China — have severely affected marketing, resulting in the worst economic outcomes ever.

I believe we are facing a shift similar to those Chilean agriculture has experienced in the past. Apples and kiwis are close examples.

Years of low prices had to be endured, cultivated areas reduced, and — of course — product quality improved in order to hope for a price recovery.

In the case of cherries, some growers and orchards will certainly have to exit the sector to rebalance production and stay afloat.

Where we stand now

By late April, the first economic returns from cherry exports started coming in… and they are not encouraging, creating major uncertainty for the next season.

How will the Chinese market behave? How should the next campaign be approached, considering each grower’s financial situation?

There are already forecasts of potential funding shortages, both from exporters and banks. However, orchard visits show that growers are already making completely wrong decisions and implementing practices that compromise productivity and — naturally — quality.

Here are some examples: growers skipping post-harvest fertilization, fewer treatments against phytophagous mites, less disease control, no summer pruning.

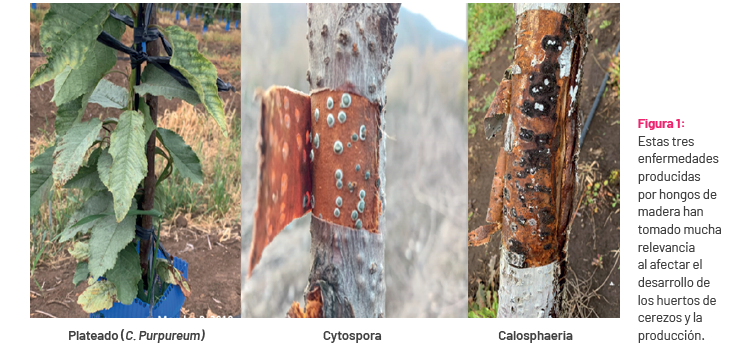

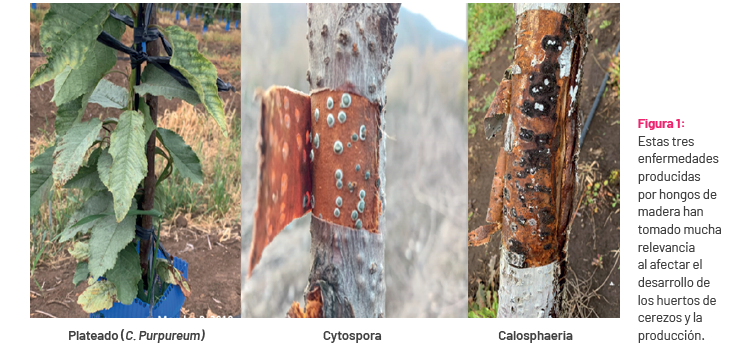

Figure 1. These three wood-borne fungal diseases have become very relevant for the development and production of cherry trees.

Figure 1. These three wood-borne fungal diseases have become very relevant for the development and production of cherry trees.

Costs: a misunderstood concept

During consultations, producers often ask me how to “reduce production costs.” I then explain the makeup of total production costs: labor accounts for about 75% of the total, and harvesting alone represents 62%.

Winter and summer pruning only account for 13% of labor costs. Machinery and fuel expenses equal 8.3%.

Crop protection and nutrition products — including pesticides, herbicides, growth regulators, and fertilizers — represent just 16.7% of the total cost. This clearly shows that we must cut labor costs associated with ineffective operations and excessive fruit harvests.

Moreover, if destined for processing, excess fruit generates additional processing costs. So reducing production may also lower handling costs at packing facilities, with a significant economic impact.

The way forward

Personally, as a grower and consultant in the cherry sector, I believe the way forward is to implement practices that add value to the fruit. This statement, with which I fully agree, comes from Professor Dr. Óscar Carrasco.

To be blunt: it is now unthinkable — as it would mean misunderstanding the current situation — to keep producing XL (24 mm) or J (26 mm) fruit, “because,” as many growers say, “they’re still paid for processing.”

These categories are no longer marketable. It is clear we must focus decisively on producing fruit of 28 mm or more, but with very high firmness — a goal that requires work and discipline.

It is essential not to skimp on seemingly minor aspects, like omitting crop protection treatments. Pest and disease control is fundamental.

Figure 2: We must maintain or incorporate value-added management of the fruit.

Figure 2: We must maintain or incorporate value-added management of the fruit.

Winter pruning

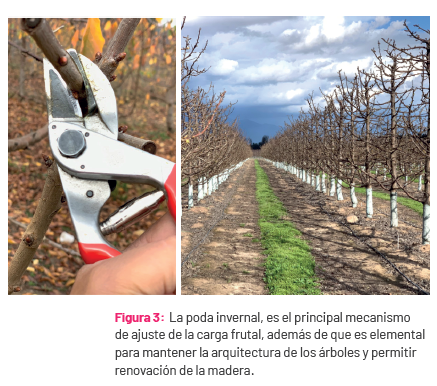

At this point in the year, the first step must be proper winter pruning to regulate crop load, increase fruit size, and consequently improve organoleptic properties.

Proper pruning also reduces future expenses, such as bud, flower, or fruit thinning.

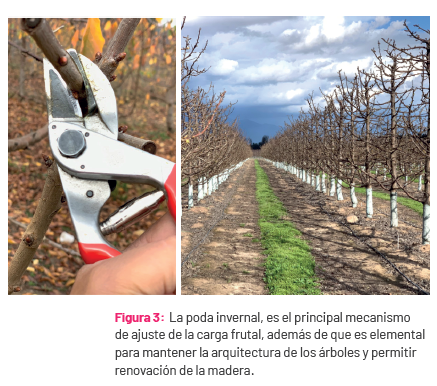

Figure 3. Winter pruning is the main mechanism for regulating fruit volume, as well as being essential for maintaining tree architecture and enabling wood renewal.

Figure 3. Winter pruning is the main mechanism for regulating fruit volume, as well as being essential for maintaining tree architecture and enabling wood renewal.

Flower or fruit thinning

We must be rigorous (and disciplined) in eliminating costly and inefficient operations such as manual thinning of flowers or fruits.

These practices are rarely well-executed and can cost up to $4,000 (about €3,700) per hectare.

Of course, depending on the soil-rootstock-variety combination, the goal should be to produce between 12 and 15 tons per hectare.

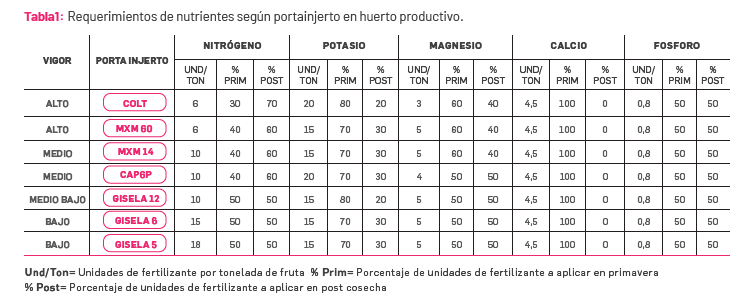

Irrigation and nutrition

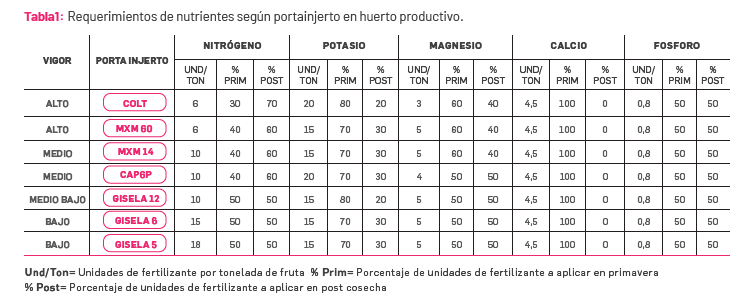

It is essential to plan soil and leaf analyses in advance and define spring fertilization programs based on expected yields.

At the same time, we must stop fearing irrigation. Irrigation timing and frequency must be better managed, as this is a production cornerstone.

Even worse, growers have stopped performing soil pit surveys (calicatas), which are an important tool to assess moisture, compaction, and the presence of root pests or diseases.

A mindset we must change

Based on my experience with all the growers I’ve worked with — Greek, Turkish, Spanish, Italian, New Zealanders, Americans, Uzbeks — we are the only ones in the world more concerned about costs than yield improvement.

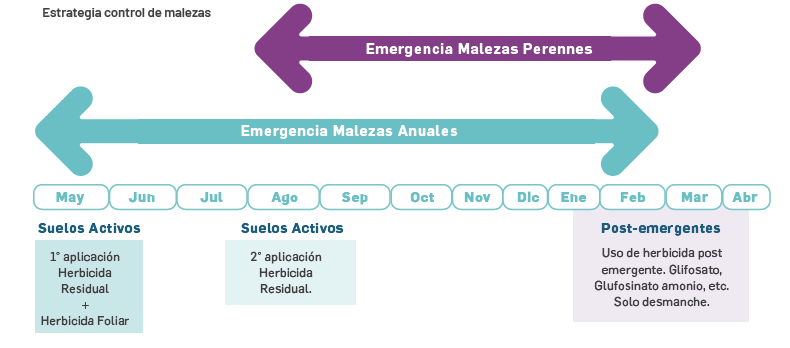

Another major issue is ineffective weed control, which undermines efficient water and nutrient management.

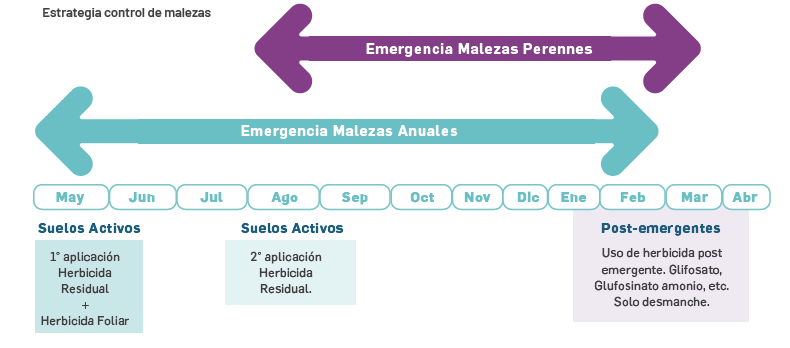

In my opinion, the key to good weed control lies in preventing seed germination of annual and perennial species. This can be achieved through the use of residual or soil-active herbicides.

Applications should begin in the second half of May, with the first rains, followed by a second application around early August.

Figure 4: Try as much as possible to eliminate flower or fruit thinning.

Figure 4: Try as much as possible to eliminate flower or fruit thinning.

A mindset shift is necessary

It is urgent to acquire the discipline needed to become more efficient. As mentioned, this may not reduce costs, but will lead to more productive spending and help us achieve better prices.

These are critical interventions in terms of planning and supervision and must be carried out at the correct times.

Proper crop load balancing, avoiding excessive yields per hectare, also directly reduces harvesting and transport costs to the processing plant.

Improving the sector will depend on the entire production ecosystem: exporters, growers, agronomists, technicians, field managers.

Figure 5: Orchard with adequate weed control with residual herbicides.

Figure 5: Orchard with adequate weed control with residual herbicides.

A negative legacy for the next season

We experienced one of the hottest summers in January and February, with three consecutive weeks above 35°C, during which solar screening applications were often suspended.

This was accompanied by very high phytophagous mite pressure, to which cherry trees are especially sensitive. As a result, many orchards experienced defoliation at the peak of summer.

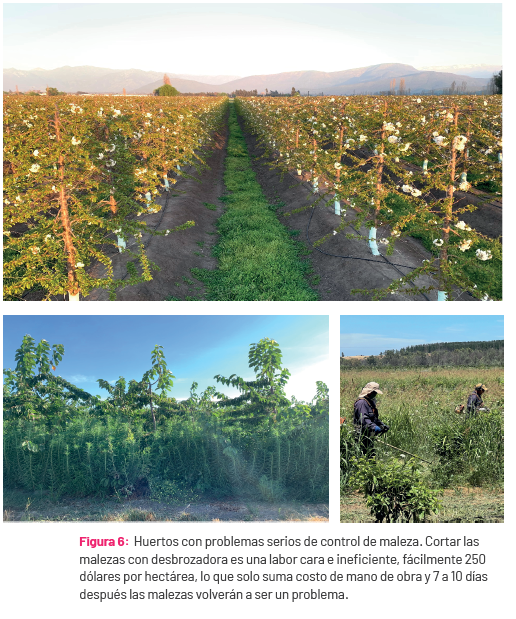

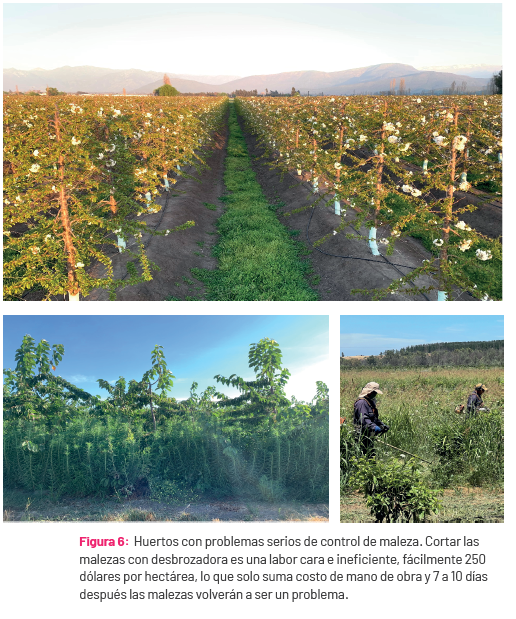

Figure 6.0 Cutting weeds with a brush cutter is a very inefficient job, which easily costs $250 per hectare, which only increases labour costs, and 7-10 days later the weeds become a problem again.

Figure 6.0 Cutting weeds with a brush cutter is a very inefficient job, which easily costs $250 per hectare, which only increases labour costs, and 7-10 days later the weeds become a problem again.

Additionally, as already mentioned, post-harvest fertilization was poorly or never done — a key element for plant physiology. All this will compromise carbohydrate reserve accumulation.

These reserves are built between January and March, so poor summer management will directly impact the following season.

Source: Mundoagro

Header image source: Opia

Patricio Morales

Cherry Times - All rights reserved