Sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) is a species of major economic interest, both for fruit production and as a rootstock and timber resource.

In recent decades, particularly in China, sweet cherry cultivation has expanded rapidly due to increasing domestic demand and export potential.

However, as observed in other countries as well, the industry relies on a limited number of cultivars, resulting in reduced genetic diversity and greater vulnerability to biotic and abiotic stresses.

A recent Chinese study

A recent Chinese study fits into this context by investigating an aspect that has so far been poorly explored in sweet cherry: the variability of the plastid genome (mainly chloroplasts), known as the plastome, which is useful for reconstructing evolutionary lineages and maternal origins of cultivars.

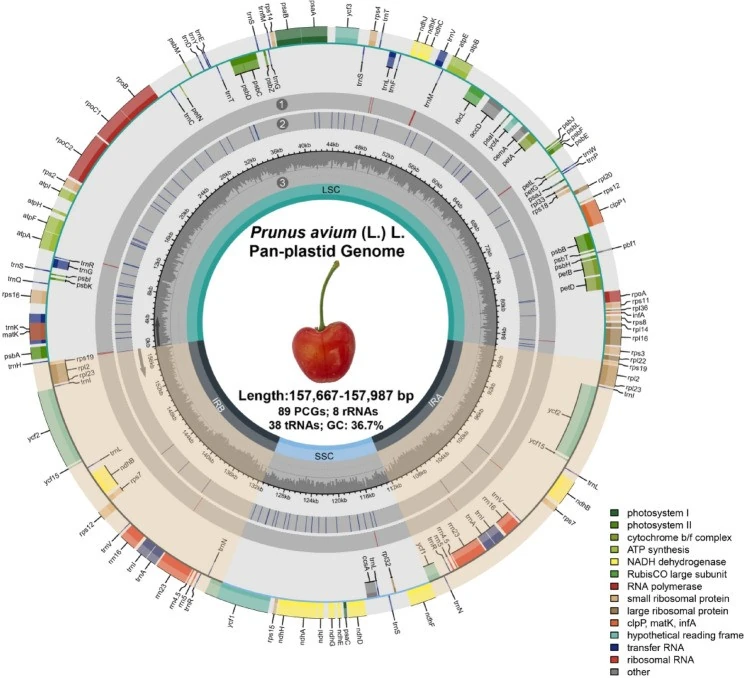

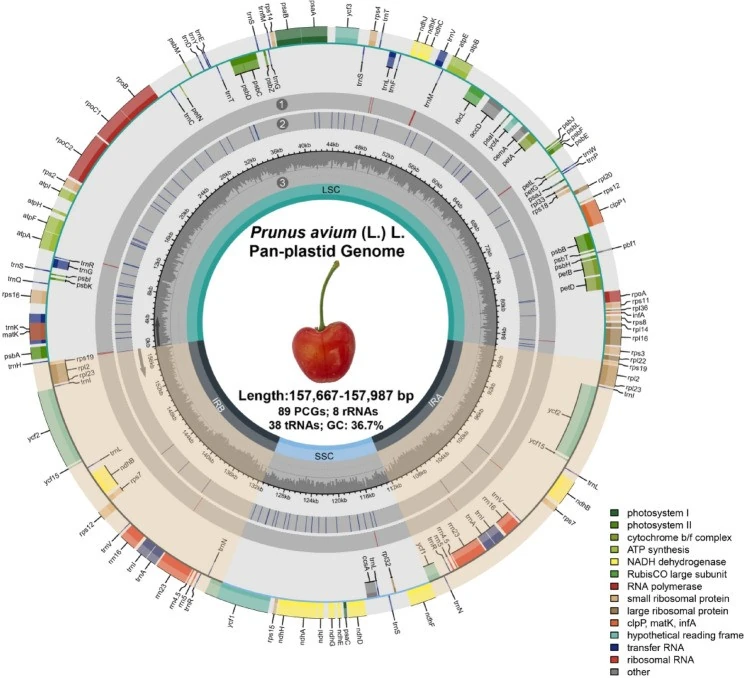

The researchers assembled and compared 110 complete plastomes belonging to 34 distinct cultivars, 98 of which were newly reconstructed from accessions cultivated in China.

The plastomes showed very similar sizes (157,667–157,987 bp) and a highly conserved structure, with a GC content of around 36.7%.

Image 1. Pan-plastome graph of 110 P. avium accessions. Genes on the outside of the large circle are transcribed clockwise and those on the inside are transcribed counterclockwise. The genes are color-coded based on their function. The light orange wedges indicate IR regions. IR (A & B): two inverted repeat regions; LSC: large single-copy region; SSC: small single-copy region. Variants in the P. avium pan‐plastome are indicated with (1) blue and (2) red lines in the grey shape circles, which representing parsimony informative sites and singleton variable sites respectively. The innermost circle area (3) represents the GC composition of the chloroplast genome.

Source: Young et al., 2025

Image 1. Pan-plastome graph of 110 P. avium accessions. Genes on the outside of the large circle are transcribed clockwise and those on the inside are transcribed counterclockwise. The genes are color-coded based on their function. The light orange wedges indicate IR regions. IR (A & B): two inverted repeat regions; LSC: large single-copy region; SSC: small single-copy region. Variants in the P. avium pan‐plastome are indicated with (1) blue and (2) red lines in the grey shape circles, which representing parsimony informative sites and singleton variable sites respectively. The innermost circle area (3) represents the GC composition of the chloroplast genome.

Source: Young et al., 2025

Despite this stable structure

Despite this stable structure, a total of 170 variable sites were identified (mainly SNPs), concentrated mostly in non-coding regions.

Phylogenetic and genetic structure analyses revealed the presence of three major evolutionary lineages (clades) within the studied accessions.

Two of these lineages showed extremely low diversity, suggesting a shared maternal origin and a high level of genetic uniformity driven by clonal propagation and cultivar selection.

In total, 11 haplogroups

In total, 11 haplogroups (plastid haplotypes) were identified, but about 70% of the accessions shared a single dominant haplotype (Hap2), highlighting a strong genetic bottleneck in modern cultivars.

The most diverse lineage was Clade 3, which includes historical cultivars such as ‘Mazzard’ and ‘Black Tartarian’, as well as modern cultivars like ‘Regina’, ‘Kordia’, ‘Pacific Red’, ‘Ji Mei’, and ‘Hong Zao’, in addition to a wild accession.

Another interesting finding concerns inconsistencies between nuclear SSR markers and plastome data.

In particular, accessions

In particular, accessions of the same cultivar, such as ‘Pacific Red’, were found in different clades, indicating possible different maternal origins or undocumented hybridization events.

From an applied perspective, the researchers identified mutation “hotspot” regions potentially useful as molecular markers to distinguish the main maternal lineages, including the intergenic regions psbD-trnT and petD-rpoA, and the ycf1 gene, known for its high variability.

This information may be highly valuable for breeding programs and cultivar traceability, although it is acknowledged that the plastome alone does not allow fine-scale discrimination among closely related cultivars.

In conclusion, the study

In conclusion, the study provides a pioneering “pan-plastome” framework for sweet cherry cultivated in China and confirms that modern cultivar selection has drastically reduced plastid diversity.

The presence of three main maternal lineages suggests a complex domestication history and at least two distinct geographic origins.

For breeders and technical professionals, the key message is to broaden the genetic base by incorporating wild germplasm and ancient local varieties.

This strategy is essential to improve sweet cherry resilience and reduce risks associated with climate change and emerging threats.

Source: Yang, Y., Ma, S., Wu, F., & Liu, J. (2025). Plastomic evolution and genetic diversity of cultivated sweet cherry (Prunus avium (L.) L.) in China. BMC Plant Biology, 25(1), 1043. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-07125-1

Source images: Young et al., 2025

Andrea Giovannini

PhD in Agricultural, Environmental and Food Science and Technology - Arboriculture and Fruitculture, University of Bologna, IT

Cherry Times - All rights reserved