Knowing how cherry varieties behave in the conditions of the Maule region, better understanding the interrelationship between the amount of cold the tree is exposed to in winter and the amount of heat needed to sprout, and defining more precise ways of measuring - with the support of technology - are the objectives of a study underway at the University of Talca's Centre of Pomaceae.

How cherry varieties cope with climatic instability

Irregular ripening has been another of the problems recorded in orchards in the central-southern region due to the climate.

2023 was perhaps the most complex year for cherry production, at least since the crop started to grow explosively in Chile. The El Niño phenomenon brought problems such as low cold accumulation due to a warmer winter, although it was not the only one, as there were also problems with budding and loading due to a cold and wet spring.

Álvaro Sepúlveda, a researcher at the University of Talca's Pomaceae Centre, has been studying the climatic effects on fruit formation since 2020, looking for innovations to be more precise in measuring cold accumulation in this crop and to move away from the traditional cold hours that are still used to measure the requirements of this fruit tree and its different varieties.

Thanks to regional research funds granted by the Maule Regional Government, the support of other regional companies, and an alliance with ANA Chile, which markets new genetic varieties, it was possible to formalise this research in order to learn about the behaviour of varieties (new and traditional) and how they respond to a climate that has changed in the central zone and that, at least in this season, has generated much uncertainty.

This was made possible through the FIC project 'Artificial intelligence applied to monitoring the behaviour of new cherry and apple cultivars in potentially productive areas of the Maule Region'.

How did this project that intertwines the climate factor with the development of cherries come about?

Traditionally, this was an apple-growing area, but today there is a large area of cherry orchards. It is important to know and see how they behave, especially because of the need for cold, which is an important factor in their development, and especially because for new varieties, their behaviour is only known in the area where they were obtained.

For example, with regard to the new German varieties, we only have information on what happens in Germany, but not in Chile. We also have no documented information on the cold requirements of these varieties, because they are new and could only be grown in areas with a high or medium cold record.

Colleagues at CEAF did similar work a few seasons ago for the O'Higgins region and we are trying to replicate it for Maule. The more information generated, the better. In addition, we are taking advantage of the fact that there are several producers, especially of cherries, who are looking for varieties and early harvest areas where there was traditionally no cherry production, for example in arid areas such as Pencahue, near Talca. There are new plantations there and we wanted to see how they performed.

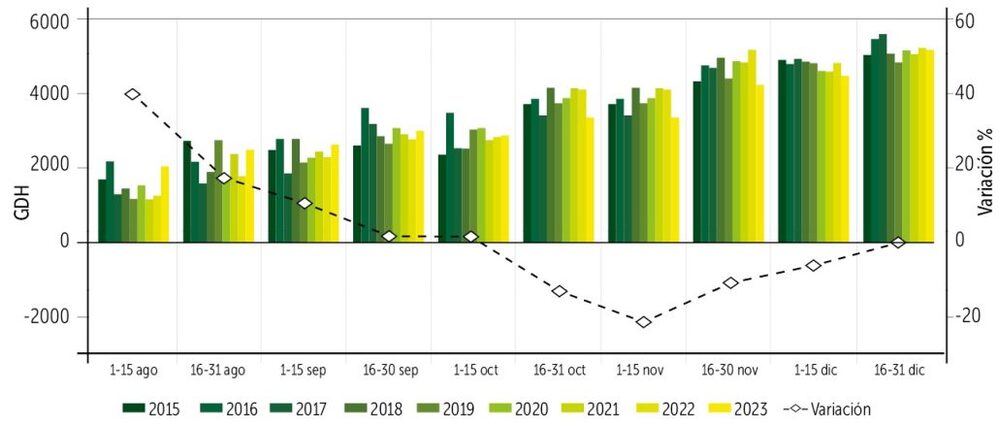

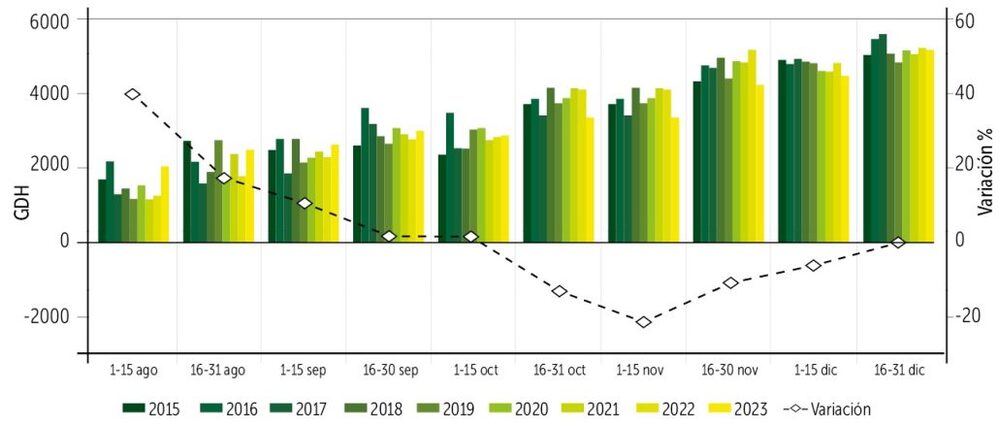

Image 1: Change in cold accumulation of seasons 23-24 compared to the average of previous seasons, August to December.

How do we measure the variables of cold and heat?

You can get the chill requirement in two ways, one is to have a lot of data over many years, and with that you do a statistical study to see how the trees behaved: when they flowered and how cold they needed; but we don't have this old information.

So we did empirical research: during the winter we periodically go out into the field and collect twigs that undergo forced budding in a growth chamber. In our case, we did this with the new varieties.

We contacted several orchards, where there are mainly varieties brought by ANA Chile, we met to see which varieties they were interested in analysing or if they had a different production system they wanted to evaluate, for example production in the hills and then analysing if it is different from the lowland area.

Our goal is to define more precisely the requirements of these new varieties and to see if there is an interrelation between the amount of cold the tree is exposed to in winter and the amount of heat it needs later to germinate.

In 2023, the weather conditions formed a perfect storm that reduced the production potential of many orchards, due to the poor cold accumulated...

When we talk about cold requirements, we are referring to a minimum amount of cold that the tree needs in order to sprout 50 per cent of the buds, which does not necessarily mean that the buds will be of good quality, nor that you will have high production. It only tells you that it saves the season.

In very cold winters there is no need for such a warm spring and you will have a spectacular, super-concentrated and more or less early flowering. But in warmer winters, like last year's, although the required values for the different varieties were met, the cold was not abundant.

Then the spring started like a racehorse, in August it looked good, but in September it collapsed. The spring was not warm and did not make the contribution it should have made to compensate for the low cold intake of the winter. As a result, there were very large and late flowerings, with buds that were not of very good quality, buds that came from the very stressful and hot summer of 2022.

There were therefore no conditions for a good development of these buds in winter and the resulting buds gave flowers of inferior quality, with short-lived ovules, giving less chance of pollination and therefore less chance of fruit set, the opposite of a cold winter.

Lack of data

The work started with traditional varieties, where we could see experiences such as that of a grower in San Clemente, who installed a shading net in winter, even without having cold weather problems in the area, and found that this shaded area in winter had better production, more fruit and more kilos.

"We want to see what happens. We did some tests to see what the relationship between cold and heat was like, which has been described for some years by researchers who are working on this, but for the moment it is an idea, a conceptual relationship, it has not yet been defined as the amount of cold."

"We don't even know if there are other variables at play. For example, there was very occasional but intense rain this winter, and it has been described that rain or cloudiness also plays a role in the dormancy process. Another aspect we are looking at has to do with these other climatic variables on shoot development through dormancy,' explains the specialist.

This is why, in addition to traditional varieties such as Santina, Regina and Lapins, new varieties, such as the Sweet family from the University of Bologna in Italy, as well as other developments such as Nimba cv, Pacific Red cv, Polka cv and Frisco, were included in the study.

So the idea is not just to measure the variable of chill requirements, but to go further?

With this project we also aim to remove the doubt as to how much difference there is between the air temperature in winter, because all these cold storage models are based on the temperature of the air and the temperature of the fruit tree, bud or branch.

We are working on this with the FabLab group, engineers at the university who make prototype sensors and data loggers to measure the temperature of the trees in the orchard. We are analysing this and, depending on the results, we could think of a sensor, mass-produced, that would more accurately record the cold that the tree feels. Technology has come a long way, so it is now easier and cheaper to make these devices.

Sensors for measuring wood temperature

How has the El Niño phenomenon affected the Maulina area, with less cold accumulation in winter and a colder spring?

We saw similar behaviour in the central zone, with the Biobío as the border. We had a winter with less cold and spring rains. Now, the positive aspect of this phenomenon is that it stops frosts, so there have not been very specific cases in the central zone, but in the south there have been significant frosts in mid- or late October, for example in the Angol area, and they have also had a colder spring. This El Niño brings us a more maritime climate, which means that in November we had very low temperatures, both in terms of daily maximum and minimum temperatures.

C'è una nuova normalità per la zona centrale?

Experts have been saying for more than a decade that this climate change would lead to a long-term redistribution of species in agriculture. And that is more or less what we have seen in the case of apple trees in Chile. Now, also in the case of cherries, it is a combination of climate change and the search for cooler and warmer conditions in spring, as the industry's goal is to supply the Chinese New Year.

To achieve this, it is necessary to go out earlier, to escape the peak of supply and harvest earlier. But there are also other means to do this, such as the use of shade nets in winter and perimeter fences that help to anticipate the harvest.

In fact, colleagues have reported to me that those who have adopted some form of environmental modification, despite the low cold, have had a very good yield, mainly because they generated more heat in the spring and this heat compensated for the lower winter cold.

Due to climatic instability, investing in some kind of covering system is becoming almost mandatory...

It is also said that this transition period to a new climate brings many extreme events, so what El Niño did, for example this year, was to enhance these changes. That is why we now have these atmospheric rivers, because El Niño provides a lot of water to these rain events.

What we have seen in these environmental modification systems like the macro tunnels is that they are designed in the northern hemisphere, in cold areas, so the behaviour is very different. In cold areas, these macro tunnels give the fruit trees a more 'normal' environment, whereas what we do is give them warmer conditions at a time when it is still winter, with days that are not so long.

What we have seen with these tunnels, and here there is agreement between academics, fruit growers and consultants, is that in the case of cherries you will have softer fruit, and this is attributed to the fact that during the growing period of the fruit, being subjected to a higher temperature condition and also lower solar radiation, because even though the canopy is transparent, the solar radiation is still very low, the vegetative growth of the bud is stimulated more.

In particular, calcium passes through the transpiratory pathway to the sprout and feeds the fruit less, leaving it with a calcium deficit and a nutritional disorder, which is what we will see later as softer fruit or with some kind of alteration. So it is not so easy to get to and use this type of tool.

Extended flowering, one of the problems caused by climatic instability

Is there anything that has caught your attention from the studies you have conducted on new varieties as opposed to traditional ones?

That is more or less what is expected at the moment. What we want to do, and what might be interesting, is to use the growth chamber to identify when these varieties go into dormancy. Because the idea is that the deep stage of dormancy, which is endodormancy, starts when 50 per cent of the leaves have fallen, and that's when the cold count starts, and all the cold that is counted before then is not effective in meeting the requirements.

But there are other studies in Europe that suggest that, in the case of the cherry tree, the cold count should be done when leaf fall has already begun, even a little earlier. What we want to see, through this same procedure of harvesting the buds, is when the buds are no longer able to bud and have entered this stage of recession, which will give us two points: a more precise beginning of when to start the count and then to see when it comes out of dormancy.

Would having a more accurate chill requirement count allow better use of products to induce and interrupt phases?

Of course, just as there are products to delay leaf fall or products that are applied to come out of dormancy. Our goal is to have more certainty about when and how to do this more precise cold monitoring in order to be able to make these managements.

In other words, if we need 30 portions of cold for a certain variety, we can monitor how these portions of cold are administered, so that we can define when we want to make some kind of application.

Should we rethink the way we count or measure cold?

In any case, I still hear talk of cold hours, which has been obsolete for a long time. The same goes for those who wonder whether cold portions can be converted into cold hours, or whether there is an equivalence or not. What happens is that generally if you look at the tables in which the cooling requirements are presented, you see it in different ways.

Unfortunately there is still little information available, although there is already agreement among academics, researchers and consultants that the cold portion model is the one that best explains the process of dormancy, and is used in warmer areas, such as those we will be facing from now on. Before this was not a problem, there was cold to wallow in.

Source: Redagrícola

Images: Redagrícola

Cherry Times - All rights reserved