Over the last decade, Chile has transformed the cherry into its leading crop: an industry that has multiplied exports, rising from 12 million dollars (about 11 million euros) to over 1,000 million (around 920 million euros), gaining global presence and revolutionizing its agricultural calendar.

Its success combines climate, technical management and an explosive Asian demand. This model continues to open opportunities for Peru as well, especially in high Andean areas with cold climates such as Huaraz, the “Peruvian Switzerland”.

Growth of the Chilean industry

Ten years ago, Chilean cherry exports were a small but expanding activity. Today, between January and October 2025, they have consolidated as one of the pillars of the fruit sector. In this period, Chile exported 463,565 tonnes for 1.846 billion dollars (about 1.698 billion euros): figures that contrast with shipments ten years earlier, which reached barely 4.5 tonnes for 12.2 million dollars (about 11.2 million euros).

The growth has been constant, driven by the rapid expansion of cultivated areas, by the use of technical practices to obtain larger and firmer sizes, and by the consolidation of a market that rewards premium fruit: China.

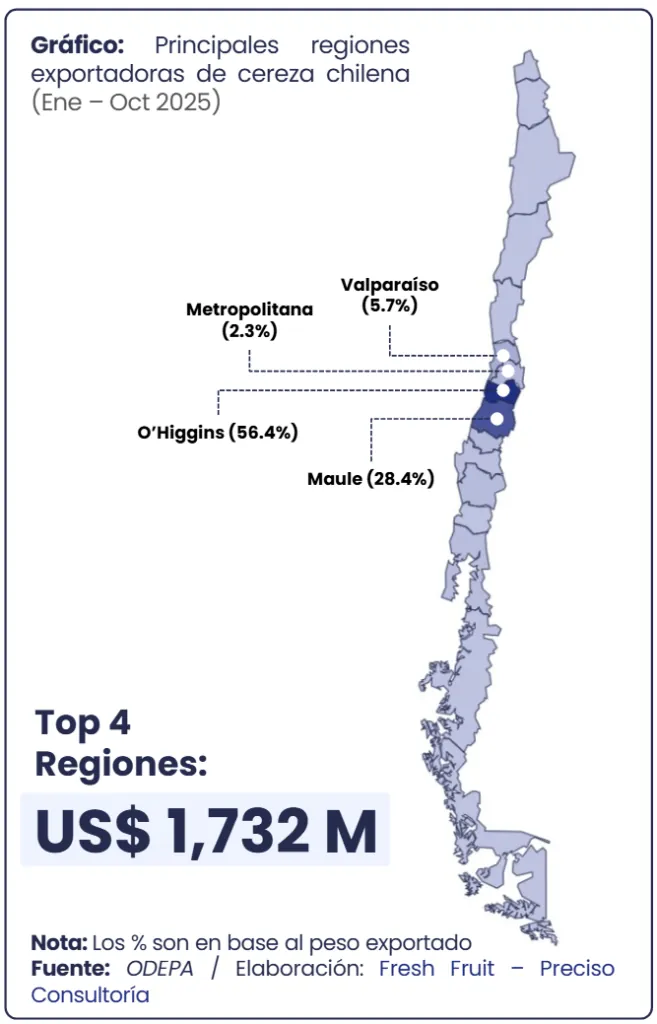

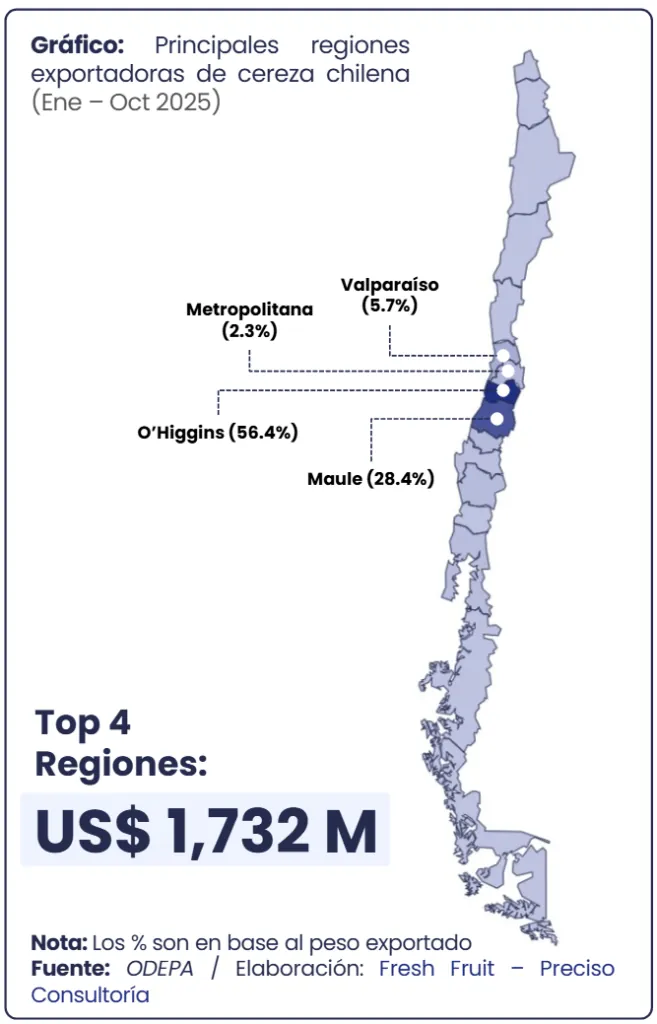

This growth is also reflected in the production geography. The regions of O’Higgins, Maule and Valparaíso concentrated most of the exportable supply. O’Higgins accounted for 56% of the total exported volume; Maule 28%; Valparaíso 6%.

These areas stand out for their fruit-growing tradition, developed infrastructure and availability of qualified labor, but above all for a fundamental factor: an extremely favorable climate for this crop.

Graph 1. Annual evolution of Chilean cherry exports

Graph 1. Annual evolution of Chilean cherry exports

Climate: the real production engine

The productive core of Chile is found in areas such as O’Higgins, Maule and La Araucanía, regions ideal not only for their landscapes, but for their climates, marked seasons and cold nights.

These conditions allow the accumulation of the necessary chill hours for the cherry tree to complete its winter dormancy, achieve uniform flowering and produce fruit with optimal color, sweetness and firmness.

These exceptional natural conditions — thanks to the thermal regulation of snowcaps from the Andes mountain range — favor increasing production; moreover, they present an additional element: summers that in some points reach 40 °C, generating a strong thermal contrast.

Graph 2. Main exporting regions of Chilean cherries

Graph 2. Main exporting regions of Chilean cherries

This alternation between hot days and cold nights is crucial to obtain the deep red required by Asian demand. From an agronomic perspective, this crop needs 800 to 1,500 chill hours below 7 °C; without such winter rest, it simply does not flower normally.

Comparison with the Peruvian blueberry industry

At this point, cherry contrasts sharply with the development of the blueberry industry in Peru. Unlike cherries, blueberries do not depend on a marked winter nor on a significant accumulation of chill hours.

On the contrary, their adaptation in Peru has been possible thanks to low-chill varieties, capable of producing in hot and non-seasonal climates, such as the northern coast.

While cherries require a cold winter to complete their cycle, blueberries can be grown in much milder temperatures, using techniques oriented toward thermal stress control and water management, but without needing a deep resting phase.

These differences explain why Peru managed to scale blueberries rapidly, surpassing the 1 billion dollar barrier (about 920 million euros) in 2020, despite producing in hot and sea-level areas.

Graph 3. Comparison of annual exports: Chilean cherry vs Peruvian blueberry (million US$)

Graph 3. Comparison of annual exports: Chilean cherry vs Peruvian blueberry (million US$)

A replicable model in high Andean zones?

In Chile, cherries reached the same milestone in 2018, but relying on a temperate-cold climate impossible to reproduce on the Peruvian coast. Both crops shared a remarkable growth speed — both surpassed the billion-dollar threshold in about eight years — but starting from totally different climatic realities.

Although the Peruvian coast does not have the necessary conditions, some areas of the country could generate part of them. The inter-Andean zones of the high sierra in the north and center, such as areas around Huaraz, present favorable characteristics: cold nights for most of the year, temperatures close to 0 °C and strong thermal contrast.

For this reason, Huaraz has been nicknamed the “Peruvian Switzerland,” a climatic coincidence that aligns with the winter rest requirements of cherries.

However, replicating the Chilean model implies more than just cold winters. In Chile, productive regions not only accumulate sufficient chill hours, but also experience hot summers, with highs approaching 40 °C.

Technical solutions and production challenges

This thermal contrast is decisive for obtaining the deep red color and quality demanded by the Asian market. In the high Andean Peruvian zones, although cold is present, the element of summer heat does not appear naturally due to altitude and constant temperate climate.

This means that the full cherry cycle — especially the phase of color and firmness development — might not fully complete in open field conditions.

Hence the idea of using greenhouses or thermal control structures (as done for high-mountain strawberry): artificially reproducing part of the summer heat to favor fruit development.

This would compensate for the missing warm weeks, but it would also increase costs and influence economic feasibility.

Furthermore, the development of scalable production will depend on: stability of chill hours between seasons, water availability, management of early frosts and logistical capacity for a delicate product requiring rapid harvesting, pre-refrigeration, packaging and transport.

Markets and the seasonal window

In the short term, Peru could aim at niche production focused on large sizes and premium markets, rather than massive development.

Between January and October 2025, Chilean shipments reached 62 countries (2 more than in all of 2024), but one dominates without rivals: China. In this period it accounted for 87%, with purchases of 402,403 tonnes for 1.614 billion dollars (about 1.485 billion euros), at an average price of 4.01 dollars/kg (about 3.69 €/kg).

After China, exports went mainly to:

- United States (4%, 21,485 t for 76 million dollars – about 70 million euros)

- Taiwan (1.5%, 4,181 t for 27 million dollars – about 24.8 million euros, 6.51 dollars/kg – about 6 €/kg)

The concentration of Chinese demand in January results from the association of cherries with Lunar New Year consumption, during which red fruits assume a cultural meaning linked to fortune.

Cherry is a highly seasonal crop. It requires intense cold in winter and accumulated heat in summer. In Chile, this sequence naturally happens once a year, producing a concentrated production between early November and mid-January.

No possibility of production exists in other months. This seasonal alignment means that Chile offers high-quality fruit exactly when Chinese demand explodes. Between December, January and February, 96% of the total is exported.

Graph 4. Main destinations of Chilean cherries

Graph 4. Main destinations of Chilean cherries

Long-term perspectives for Peru

Conversely, in Peru the Andean climate does not offer such a clear thermal cycle: cold is present, but not intense summer heat. To target the profitable window (November-January), one would therefore need to use thermal structures that simulate part of the summer heat.

For Peru, cherries will not become a major crop in the short term. However, there is a concrete opportunity in the high Andean areas (Huaraz, Cajamarca, Cusco).

The potential is real, provided that the focus is on:

- niche production

- large sizes

- windows near December–early January

- specialized technical and climatic infrastructure

The Chilean case shows that a crop can become a strategic sector when climate and technology work together. For Peru, the potential exists, but the path to turn it into a commercial reality still needs to be defined.

Source: freshfruit.pe

Image source: Fresh Fruit

Preciso Consultoria

Fresh Fruit

Cherry Times - All rights reserved