Today, more than 600 sweet cherry varieties are cultivated worldwide, and unfortunately none of them can be considered completely immune to cracking.

What do we currently know about this issue, and what mitigation strategies can be adopted? Cracking is a complex physiological phenomenon influenced by both environmental factors and multiple genes.

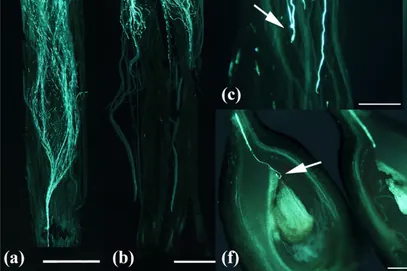

When discussing cracking in sweet cherry fruit, two types can be distinguished: 1) Macrocracking, consisting of large and deep splits that reach the inner cell layers and are visible to the naked eye; and 2) Microcracking, which is much smaller and difficult to detect without close inspection.

Cracking types and locations

Cracking may occur near the calyx, in the stem cavity, or on the cheek of the fruit. Splits near the calyx and the stem are often superficial and appear when the fruit is not yet fully ripe.

They can usually be tolerated by some consumers, provided they are not accompanied by fungal infections. In contrast, lateral cracks are much deeper and reach the flesh, making the fruit commercially unacceptable.

Many techniques have been tested to try to minimize the occurrence of fruit cracking. First, the use of protective covers (such as tunnels and rain-shelter nets) reduces the amount of water reaching plants and fruits and has been shown to lower cracking by about 40%.

Second, the application of certain compounds may help reduce this phenomenon. For example, calcium-based treatments or sodium silicate are applied to improve epidermal characteristics, but results have not always been positive.

Alternative treatments and substances

Abscisic acid, gibberellins, and methyl jasmonate may also be alternatives, although studies have produced mixed results. Finally, putrescine, glycine betaine, and seaweed extracts have been shown to reduce the incidence of cracking.

Although several agronomic methods have been proposed to limit this problem, the most sustainable strategy remains the selection of varieties that are genetically more resistant to cracking, since susceptibility is strongly cultivar-dependent.

“Cristalina,” “Fermina,” “Hedelfingen,” “Kordia,” “Regina,” “Summersun,” and “Sue” show good tolerance and therefore represent valuable resources for developing increasingly resistant cultivars in the future.

Even though progress has been made in understanding how and why these cracks occur, the complete mechanism is still unclear, especially from a genetic standpoint.

Research and genetic resistance

Future research should focus on several aspects, including: identifying new genes involved in resistance to cracking; clarifying which genetic pathways regulate the activity of enzymes influencing crack formation during ripening; and analyzing the metabolome of different cultivars at various developmental stages to understand how chemical changes relate to the plant’s genome and proteome.

In conclusion, fruit cracking in sweet cherry is a complex issue that requires further study and strong coordination among researchers, agronomists, and breeders.

Only by fully exploiting the genetic resources available will it be possible to effectively address this challenge.

Source: Xu J, Chen L, Dong J, Jiang L and Hong L (2025) Overview of fruit cracking in sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.): causes, testing methods, mitigation strategies, and research perspectives. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1534778. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1534778

Source images: SL Fruit Service

Melissa Venturi

University of Bologna (IT)

Cherry Times - All rights reserved